* *

An attractive figure rounds the corner. Is he? Yes, very. Your gaze locks in his. The moment dilates. Take in the hooded eyes, the aquiline nose. Zero the body. You feel a flush of arousal, a stirring below. Your pulse grows palpable. The mouth wets but you can’t swallow.

* *

The scene was…imbued with a strangeness, or if you like a naturalness, the beauty of which continued to grow. For all that M. de Charlus had tried to assume a detached air, distractedly lowering his eyelids, every now and again he would raise them again and give Jupien an attentive glance.

—Proust, “Sodom and Gomorrah”

Consider the first look involuntary. You turn before you know what draws you.

The second look appraises. Scope the posture, their way of inhabiting a body. A squarish set to the shoulders, a swell in the hamstrings.

A third look, if merited, is to hook their interest. When you pass on the street, look back. When he does too, abandon all dignity and reverse course. He pauses in front of a shop window, resting his eyes on retail. Your gazes meet in the mirrored glass…

This is but one script. The means and meanings of the cruise are as open as the sites where it occurs. Sometimes to turn and look is pleasure enough. We can just look.

* *

My first cruise, or proto-cruise, was as a teen from the sticks, visiting a favorite aunt in San Francisco. My first visit to the city! As we walked up a steep hill to a Greek restaurant, a male couple bore down. I remember only the man closer to me, his taut thigh sheathed in leather, and on top, an extraordinary white quilted jacket, like fetish gear from planet Hoth. The spark when his gaze met mine wasn’t erotic. It was a welcome, an acknowledgment of kinship.

Before apps, cruising was a primary initiation into gay life. Traveler, you have found your tribe. Each subsequent cruise reinitiates the pledge. It’s a ceremony held in air, a portal that might open anywhere, right in front of Williams and Sonoma. Right at the corner of Rua da Carioca and Largo do Rocio.

What can be gleaned from these street scenes without sound, figures absent or painted in?

Largo do Rocio, circa 1875.

* *

In 1878, the secretary of Rio de Janeiro’s police complained of the “rampant” cruising in a downtown pocket park, Largo do Rocio. “People go there at late hours to practice abuses against morality, forcing this Division to patrol the gardens, preventing the police from being in other places.”

Cruising is still tamped at its edges by danger, shadowed by a spectral history of surveillance and exposure. It’s the wordless code that allowed gays to evade detection. Threat amplifies thrill, and soon transgression becomes a part of the ceremony.

* *

My host in Brazil, Alexandre, saw the whole seduction play out like a dance, he said. Like two fighters circling each other, bobbing and feinting. The exoticizing metaphors are his (or K’s, translating his observations later), but the anthropological frame they offer is apt.

On the round marble arena of the dancehall atrium (a bank repurposed), Wesley circles and gives me the heavy weight of his gaze. Awakened, I circle the dancefloor to return it, searching out his chestnut curls and wolfish stare. Gustavo, one of Wesley’s friends, was also circling, trying to draw my eyes. But the choice had been made, and swung forward with pendulous inevitability.

Café Criterium, located immediately across from Largo do Rocio, was a favorite meeting place for “actors and young lads with high-pitched voices who wore rice powder make-up and rouge.”

* *

In turn-of-the-century Rio de Janeiro, cruising may have begun in the streets but ended in its pocket parks. Lured by the scent of tropical plants, Rio’s flâneurs took sexual refreshment under the cooling shade of leaves.

Gardens for large cities are like escapes from civilization. Between two trees, man is completely different from the man between two shop windows.…On the edge of an artificial lake, in the shadows of old trees, the city dweller feels the atavism of his extremities, and the waking of instincts. —João do Rio

Paulo Baretto, pen name João do Rio, was the era’s most celebrated chronicler of Cariocan life. His funeral cortège is reputed to have drawn 100,000 to Rio’s streets. Like the decadents he admired, he was drawn to the more sinister aspects of city life. Though Baretto’s diaries record only one confirmed queer romance, on the French Riviera, I gather from the voyeuristic thrill he derives from his reportage that he was no dispassionate observer of Rio’s gay underworld:

Isn’t the garden a revival of the ancient forests filled with drunken revelers and satyrs? One can see nervous subjects…approaching one another, circling like vultures, murmuring proposals that make one shiver, and going into the shadows where one can do anything.

The density and anonymity of city streets allowed queer men of many classes to congregate, freed of family or fazenda. These pockets of nature—jardins in Portuguese—allowed escape from the rigid discipline of the gridiron. The tree cover allowed the flâneur to drop all scholarly remove and submit to a self-interested hunt for flesh.

* *

Failing the geologist’s field of contemplation, I had at least that of the botanist. —Proust

In a cruise, occult rituals assert themselves with a force that feels primal. In Proust’s “Sodom and Gomorrah” (book IV of Á la Recherche du Temps Perdu), gay seduction draws us close to the orders of plant and animal. The younger tailor Jupien is a receptive orchid, Baron Charlus the cruising bee. From there, the cruising grows stranger: “examined over the course of a few minutes, the same man seems successively to be a man, a man-bird, or a man-insect…” Paradoxically, these chameleonic changes bring the cruisers back in the end to human artifice, to a “rehearsed” sequence of mirrored poses:

[Jupien] was capable of improvising his part in this sort of dumb show which (although he found himself for the first time in the presence of M. de Charlus) seemed to have been long and carefully rehearsed; one does not arrive spontaneously at that pitch of perfection except when one meets abroad a compatriot with whom an understanding then develops of itself… But, what was even more astonishing, M. de Charlus’s attitude having changed, that of Jupien was at once made to harmonize with it, as if in accordance with the laws of some secret art.

Although Proust’s (nominally heterosexual) narrator is careful to show his distance, the scene itself is so impossibly cartoonish, one feels that Proust cruising us in the pitch of his writing. No mere glance, but a gaze “transfixed.” Jupien poses in exaggerated contrapposto. See Charlus push out his chest, “embonpoint,” with gusto.

Michael Moon calls this mode hypermimesis. Against the homophobic canard that queer sexuality is imitative and false, Moon asks, what if queer ways of being are in fact grandly imitative? Camp and drag are two obvious hypermimetic modes. The exaggerated masculinity of 1970s clone culture is another, more sexualized form. (The ’70s is the moment when, in some zones, cruising brandished the danger that had long dogged it. Think of a leather harness, chaps, a stony gaze, Tom of Finland’s testosterone overdose.) In a cruise, a conventional mode of sexual appraisal—the sly glance you clock but pretend to ignore—is amped up. Glance becomes gaze. Not the mirror stage but the mirror stare. When reciprocated, a cruise gives you the uncanny effect of seeing your own desiring gaze amplified and mirrored in the eyes of your fellow queer.

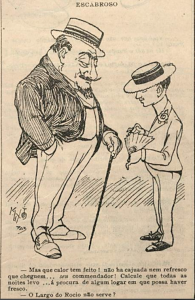

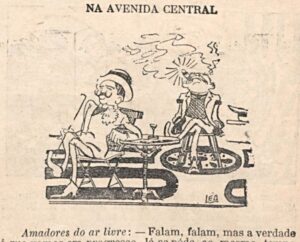

—How hot it is! There’s no cashew juice or anything that offers refreshment. I reckon every night I’m out searching for something fresh.

—Won’t the Largo do Rocio do?

* *

Won’t the Largo do Rocio do?, the large-headed figure asks the youth shyly regarding the petaled folds of a fan. In contrast to the literary forms European decadence took—the Yellow Book, the novels of Huysman and Wilde—the visual archive of fin-de-siècle Brazilian cruising is brazenly visual. This cartoon is one of many sprinkled throughout Rio’s popular satirical weekly, O Malho, from 1904 to 1909. These drawings comment knowingly on the poses of prostitution and male cruising (at times indistinguishable from normal flânerie) and the sites where it clustered in a rapidly modernizing Rio: the pocket parks Largo do Rocio and Passeio Público.

Offered as a gross satire of queer—perhaps also interracial—appetite, the look of this lusty Brazilian Charlus does not only lampoon a queer pick-up; it is a covert advertisement for it. Proust’s law of homosexuality (and Jewishness) is that it takes one to know one. Whoever drew this cartoon knew the varieties of homo-zoological type and where to find them. The cartoon traces the lineaments of queer desire, and in doing so, teaches it.

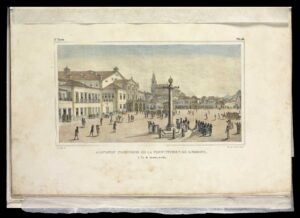

Largo do Rocio, circa 1821, when it was rechristened Praça Constituição.

* *

By the turn of the century, no place name in Rio was queerer or more notorious than Rocio. The pre-history of the square itself—a contest between state control and insurrection—casts a suggestive light on its later use as cruising grounds.

Originally a swampy grassland, the area was cleared by Portuguese colonists for public displays of corporal punishment, particularly against African descendants who attempted to escape the cruel bonds of slavery. (It received the name Rocio or Rossio, the spelling of the original square in Lisbon, when it became the theater and entertainment center of Rio in the early 18th century.) In 1821, it was rechristened Praça Constituição when regent Dom Pedro de Alcântara was forced to renew the colony’s allegiance to Portugal on a balcony overlooking the square. Note the sparsely populated foreground in his composition above; you could almost miss the meager audience Debret places at the vanishing point. The column at center right, evoking the pillory and guillotine, reminds us of the square’s long history of discipline and punishment.

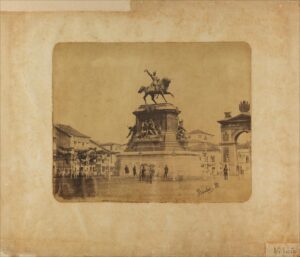

The statue of Dom Pedro I when installed in 1862.

* *

I am looking at eyes that looked at the emperor’s. —Roland Barthes

Emperor Dom Pedro I declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal one year later, in 1822. (Brazil was briefly the seat of the Portuguese empire when the royal family, in flight from Napoleon, left the continent.) This short-lived allegiance to the Portuguese crown explains why the name Praça Constituicão never stuck. As long as the square remained a locus of cruising, it went by Largo do Rocio.

A statue of Dom Pedro I was placed at the square’s center in 1862, and soon after, a green skirt of park surrounded it. Writing in 1901, Luiz Edmundo captures the irony that a political monument should become a beacon of cruising: “After eight at night lads with feminine airs, who spoke in a falsetto voice, bit on cambric handkerchiefs and laid their sheepish eyes on the manly and handsome statue of Mr. Pedro.”

* *

“Á procura de algum logar em que possa haver fresco?” Do you know where I could find some refreshment? the youth asks his admirer. Secreted within the innocent query is the Cariocan codeword for queer: fresco.

The 1903 Dicionário Moderno defines fresco as an “adjective meaning cool weather, depraved due to modernization. Almost cold, mild, agreeable, that which is neither hot nor warm. That which is whimsical and breezy. One finds them in the hills and in the Largo do Rossio.” How subtle and cunning the swerve from atmosphere to body.

“Amadores do ar livre.” Lovers of fresh air relax

and “tomar fresco” on a patterned calçada.

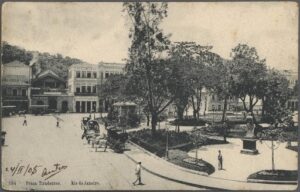

Largo do Rocio, Rio de Janeiro, 1908.

* *

Beyond sexual refreshment, “fresh air” bore a complicated and torturous relationship to public health concerns in the period. The fetid urban air of downtown Rio—hemmed in by its famously scenic hills—was viewed as a hazard for plague and yellow fever, in a holdover of miasma infection theory. In a photograph dated 1908, we see on the left edge of the composition the foothill Morro do Santo Antônio, which was later razed to improve air circulation.

In Eugenics in the Garden, Fabiola López-Durán shows how modernist concerns about air quality veiled a racist campaign to remove the poorer populations living on the hills in the city center. (The umbrella term was “antropogeography,” which Le Corbusier picked up from his visits to Brazil and redeployed in his own eugenicist writings.) As the Dictionário Moderno suggests, the communities of Afro-Brazilian migrants who lived in the hills overlapped with the frescos who cruised the urban center below. It’s seems curious to us now that fresco should be viewed simultaneously as a symptom of urban decadence—the homosexual body—and a cure for the maladies of city life, in the form of fresh air.

A 1910 map of the Centro area of Rio, showing two hills that were removed for public health. Morro do Santo Antônio, at the top, separated the two cruising grounds, Praça Tiradentes (aka Largo do Rocio) at top right, and Passeiro Público, top left. The hill at the bottom, Morro do Castelo (or Castello) was removed in the 1920s.

**

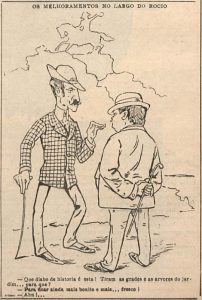

More than a name change was required to clean Largo do Rocio of the moral stain of cruising. In 1906, the park underwent several renovations, which did not go unnoticed by the city’s satirical weeklies. First a neoclassical balustrade around the park was dismantled, and soon after, much of the greenery was removed. The editors of O Malho saw through the official pretext of these renovations—to improve the city air—and connected the redesign to the park’s reputation for cruising. A trolling cartoon in O Malho suggests that the removal promoted fresco—fresh air as well as queer cruising—rather than deterring it.

—What the hell happened here? They took out the railings and the trees of the park…for what?

—To make the park more beautiful and more…fresh [fresco].

— Ahhh!…

Passeio Público in its original French parterre style, designed by Mestre Valentim.

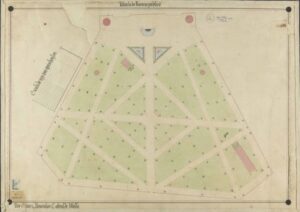

Redesign by Auguste Glaziou, 1860–62, in the English style

* *

The redesign of public space is a way to control populations, and parks and gardens are more amenable to this renovation than architecture. Although the removal of trees from Largo do Rocio may have inhibited the cruising, it’s important not to overlook the influence of the park’s serpentine pathways—a leisurely and sensuous reprieve from the hectic gridiron of the streets—as an abiding incitement to cruising.

The designer of Largo do Rocio is uncredited, but we know that the other main cruising ground of belle–epoque Rio, Passeio Público, was redesigned by August Glaziou in 1862; he stayed on in Rio for decades to oversee its parks and gardens (likely including the design of Rocio later in the 1860s). Although French by birth, Glaziou’s mission in redesigning the Passeio was to remove its rigid French parterre. In its place, he installed serpentine pathways modelled on the English garden style of Hyde Park, which were better suited to promenading and, it turns out, cruising.

* *

If cruising is a coded language, what messages does the cruiser’s peregrinations convey? If we could trace cruisers’ walks along the sinuous paths of Rocio and Passeio Público as if on a map, what would these tracings spell?

* *

If cruising is a “backward glance that enacts a future vision,” as Jose Muñoz writes, what can we make of the lost futures glimpsed in the rear view? How should we memorialize queers for whom cruising was not even a thinkable utopia?

As this dossier of photographs and drawings makes clear, free movement in the public sphere was a privilege mostly enjoyed by cis-gender males. Yet it’s not difficult to imagine how cruisers of all genders and identity positions were drawn to Rocio—for the shops, theaters, and bordellos surrounding it, if not the park itself. Think of the corseted femmes locking eyes over the latest silks from Paris. The society women exchanging glances over custard tarts at Confeitaria Colombo. The adventurous butches donning waistcoats to visit brothels that lined the square.

Evidence of trans and lesbian desire in Brazilian art and literature is scant and often phobic. The first literary appearance is Aluísio Azevedo’s 1880 novel O Cortiço (The Slum), in the rape of an underage virgin by an older prostitute. Laura Villares’s 1926 novel Vertigem (Vertigo) contains the first lesbian character written from a woman’s perspective, yet this depiction too is negative, with coerced sex. It would not be until Myriam Campello’s 1981 Sortilegiu that a Brazilian novel written by a woman would capture the full complexity of lesbian desire.

When Clarice Lispector wrote about lesbian coupling in her story “The Body,” she cast her two female protagonists as anti-patriarchal murderers. (Lovers of the same man, they kill and bury him in his yard then escape together to Montevideo.) Many cis–hetero heroines in Lispector’s fictions are flâneuses and sexual cruisers of a sort, bristling against the constraints of female roles in their rough travel through the city. Psychogeography is often a prelude to psychic crisis. We can even read Lispector’s story “Love” as a photo negative of the gay male cruising seen in this dossier. Ana, a “sight to behold,” is unsettled by the uncanny absence of the male gaze while out shopping for groceries. She finds herself on a tram, involuntarily drawn to a blind man who cannot return her stare. When her unreciprocated gaze prompts an existential crisis for Ana, she disembarks the tram with a grocery bag of broken eggs, seeking refuge under the palms of Rio’s famed Jardim Botânico. Unlike João do Rio’s cruisers, she finds the garden’s teeming flora and insect life abject rather than liberating.

* *

My boyfriend was recently cruised while walking through Morningside Park—an Olmsted design. Like many of us during the coronavirus pandemic, he and the stranger wore face masks sheathing nose, mouth, and chin.

What an odd time to be cruised, he said, because how do you know who’s cute? He said he’s rarely aware of anybody cruising him—maybe four times in his life. (I don’t believe him.)

You still have the body to admire, I countered.

And don’t masks make eyes even more of an erogenous zone?

In this moment of social distancing, the eyes are where we turn to assess threat. Will you come too close to me? Yet this heightened danger in proximity may spark a renewed erotics of the gaze. Cruising was always a rebellion against the dulling pressure of social conventions. Forbidden to touch, we can still fuck with our eyes.

* *

…at the end of the evening, when the signal is made that the park’s gates are to be closed, while most people push and shove to leave, exhausted as if they had just finished a long trip, those lingering behind take advantage of the relative solitude, and the garden convulses in a supreme spasm. —Paulo Baretto as João do Rio

Today, Largo do Rocio (now called Praça Tiradentes) is denuded of foliage, but the Passeio Público retains its greenery and elegant Glaziouan design. One can imagine queer ghosts cruising its serpentine paths, searching for fresco—refreshment—and a better future they would not see with their own eyes. In their cruising, did they bank this utopian vision in the eyes of other cruisers, who pass it onto the next generation, and so on? Let this shared vision of a queerer future never fade.

O Passeio Público, Rio de Janeiro. Photograph Marc Ferrez, ca. 1875.

Christopher Schmidt is the author of The Next in Line (poetry), Thermae (chapbook) and The Poetics of Waste (criticism). Recent writings have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Contemporary Literature, ArtMargins, and Bookforum. He is currently completing a book of site writings on Elizabeth Bishop and landscape design in Brazil.

__________________________________

Image Credits

- “Largo do Rocio grande. Hoje Praça Tiradentes.” Photographer unknown, ca. 1907. Postcard.

- “A Praça da Constituição, Rio de Janeiro.” Photograph by Marc Ferrez, ca. 1875. Photograph Mark Ferrer. Albumen silver print. 19.1 x 25.3cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Gift of Joseph R. Lasser and Donald I. Reifler. Digital use courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

- “Praça Tiradentes, Rio de Janeiro.” Photographer unknown. Postcard, edition A. Ribeiro. 14×9 cm.

- Cruisers photo collage. Fair use.

- Illustration by K. Lixto [Calixto Cordeiro]. O Malho (Rio de Janeiro) 2, no. 20 (March 28, 1903): 14. Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

- Illustration by Jean-Baptiste Debret. “Acceptation provisoire de la constitution de Lisbonne: à Rio de Janeiro, en 1821,” Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil. Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

- Statue of Dom Pedro I. Photograph by Manoel Banchieri. Albumen print, 23 x 32 cm. Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

- O Malho (Rio de Janeiro) 5, no. 183 (March 17, 1906): 24.

- “Praça Tiradentes” [Largo do Rocio]. Photographer unknown. ca. 1908. Postcard.

- Map. “Planta da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.” Designed by Francisco Jaguaribe Gomes de Mattos for the Conselho Superior de Instrucção Publica. Rio de Janeiro: Julio Soares de Andréa & Co., 1910.

- O Malho (Rio de Janeiro) 3, no. 91 (July 11, 1904): 24

- Mestre Valentim’s Passeio Público, Rio de Janeiro, drawn by Elias Wenceslão Cabral de Mello, ca. 1850. Ink and watercolor on paper, 41.5 x 58cm. Acervo da Fundação Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

- Auguste François Marie Glaziou’s design plan for the Passeio Público, Rio de Janeiro, 1862. Watercolor on paper, 75.5 x 56cm. Acervo da Fundação Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

- Passeio Público, Rio de Janeiro. Photograph Marc Ferrez, ca. 1875. Albumen silver print 18.7 × 25.3 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Gift of Joseph R. Lasser and Donald I. Reifler. Digital use courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.