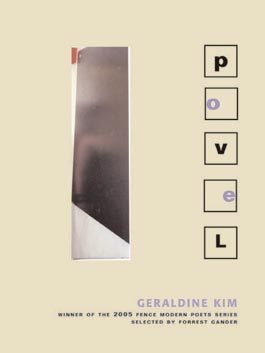

Povel is a compulsive reading and writing experience; a fantastic, extended excursion into the mind and life (in words) of Geraldine Kim, a young first-generation Korean-American woman born into the most modern of all situations: the end of the 20th century in a small town in New England, whence she launches herself through venues urban and cerebral, academic and commercial. The book-length poem’s stream of consciousness is trained and leashed, and its form is strictly, if arbitrarily regulated by another of our most modern conveniences: the justified stanza, which provides not only a container for the author’s thinking, saying, and doing, but also a means of signification: This is a poem-novel—or “povel”—by virtue of its self-reliance and its bold marking of territory. Povel is, in the author’s own words: “a successful merging between confessional verse poetry and the novel”—hence the coinage of its title. Povel is also a radical entry in the annals of the several genres. The author purports an omniscient skepticism about its future: that it will ever be read; that it can be appreciated. Its reader cannot help but be amazed and heartened at the vigor this book injects into its chosen forms, and the humor with which its despair is tempered.

The Povel may not sound like a potentially revolutionary new form but it in fact is. This is because it, and its inventor Geraldine Kim, do far more than they outrageously lay claim to—or perhaps exactly what they claim—in any case charting consciousness through observation and at the same time remapping it through rigorous prosodic attention. Scientific evidence that hysterical symptoms are not only here to stay, but structure and control our perceptions, this book dares you to attend to it. Most highly recommended reading.

—stacy doris

former teacher of geraldine kim

Somewhere over the rainbow of Lyn Hejinian’s My Life, Pamela Lu’s Pamela: A Novel, and Kenny Goldsmith’s Soliloquy, Geraldine Kim’s Povel débuts as a startling confessional, conceptual novel in verse, or vice-versa. Both culture maker and cultural processor, Geraldine Kim captures, in excess, the milliseconds of our daily ponderance—our anxieties, ambitions, jokes, authentic and inauthentic insights, etc. . . . “I gave away everything. Just like the Karate Kid series. Worrying about judgmental relatives. So that’s why they’re called arteries. I could almost touch the side of the truck. I wanted to recite everything I knew, starting with the fact that George Washington was the first president. Then how he wasn’t really the first president. Feeling like grilled cheese.” In Toto . . . we’re not in genre anymore!

—robert fitterman

former teacher of geraldine kim