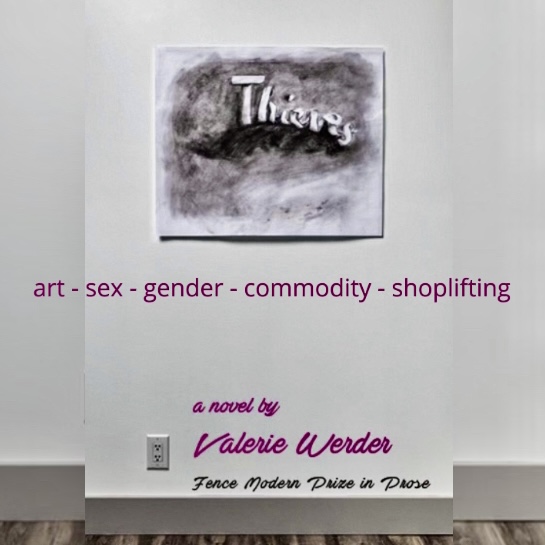

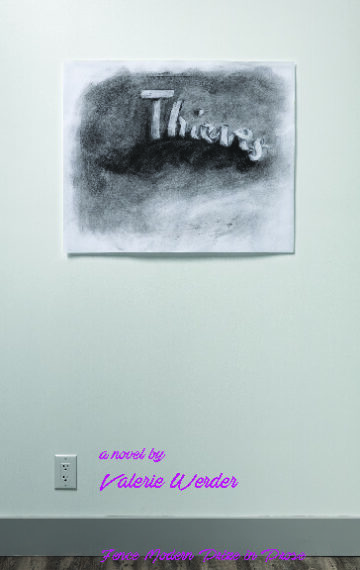

- Publisher: Fence Books

- Available in: Paperback, Ebook, Audiobook

- ISBN: 1944380213

- Published: August 8, 2023

“Sly, witty, and utterly compelling, Valerie Werder’s Thieves illuminates how we create and examine our selves in thrall to late capitalism—and how we’re all thieves of one kind or another. This novel gives immense pleasure...”

—CLAIRE MESSUD

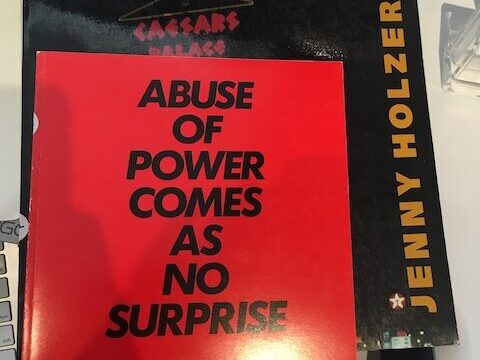

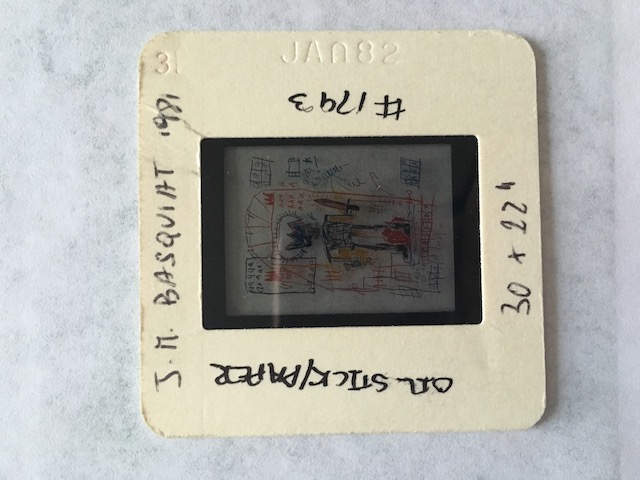

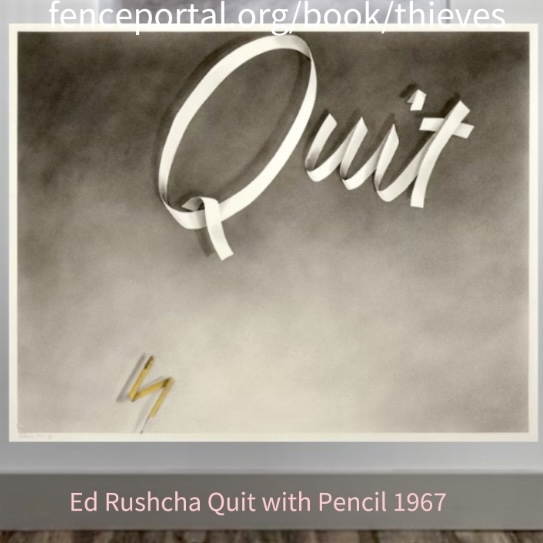

Valerie Werder’s debut novel, Thieves, is an autofictional account of the strivings and humiliations of a gallery girl, also named Valerie. The tale of Valerie’s maturation, her life and adventures in sex and crime, exquisitely eviscerates the industries of desire and consumption which produce, place a value on, and limit her creativity, freedoms, and responsibilities.

As the novel begins, Valerie is an art worker in the big city, a product of an American childhood in a small place where she learned to cherish objects and their promise. The magic of being, thinking, speaking, and writing is all bound up for Valerie, a self-aware creature and expert weaver of language in "the sales game." Valerie generates scaffolds of empty sales copy and lives in a storm of things, many of which are commodities—including herself. All the while, she becomes increasingly aware of the ways she can acquire and be acquired.

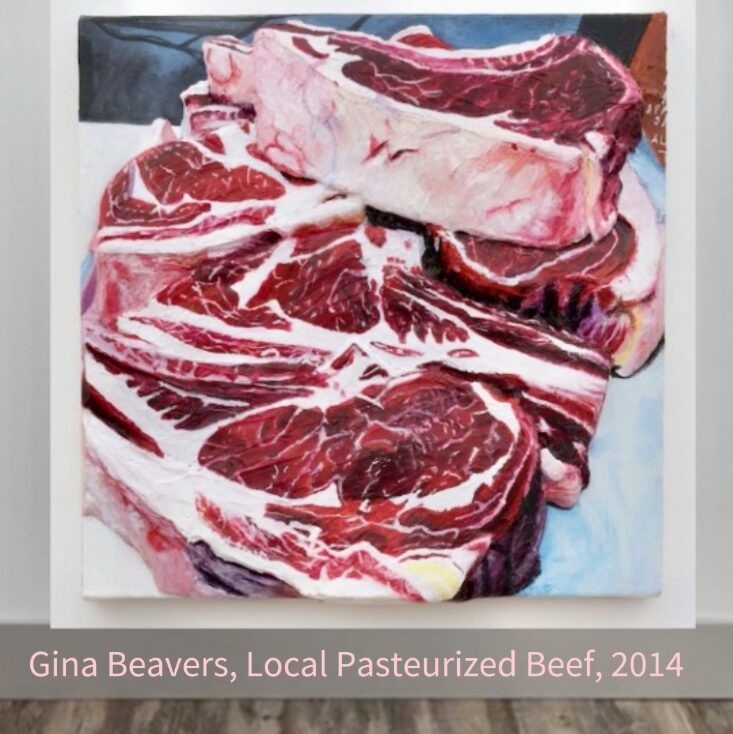

Watch as Valerie falls for the dashing and irresistible master shoplifter, Ted. Follow along as she begins to uncover Ted's shady past and secret lives. Along the way, you will, with Valerie, encounter: bleeding meats suavely tucked into Ted's loose jeans, the strangely seductive language of the highly personalized and persistent emails sent to Valerie from her local bank branch, and Valerie's vivid dreams, including one in which the minds of the women of New York City are uploaded into identical metallic cyborg bodies.

In whip-smart, sharply humorous prose, Thieves is a wild, dark, and rollicking ride through a beguiling and dangerous Willy Wonka factory of gender, capitalism, sex, and art.

Selected for The Fence Modern Prize in Prose

Listen to an excerpt from the novel below, and scroll down to the bottom of the page to read along with the visual text of the excerpt.

Thieves is now available also as an audiobook whereever audiobooks are sold.

Praise for Thieves

“With great wit and charm, Valerie Werder unravels the story of a life in order to expertly wind it back around her finger. Thieves is a gleaming gem of a novel. It joyfully ransacks literary convention—borrowing, repurposing, stealing—but the result is entirely Werder's own.”

—ELVIA WILK

“If you need a brain massage or to have your heart restarted, Valerie Werder’s prose is the place to go. Like an epic phone conversation with your most resourceful best friend, Thieves is full of detail, empathy, and not a few pieces of precious advice. In this book, I finally found out how I lived.”

—LUCY IVES

Listen to Valerie Werder's curated THIEVESONGS playlist on Spotify: songs related to her writing of the novel.

Read an interview about the novel with Valerie Werder and Fence Co-Editorial Director Jason Zuzga.

JZ: What made you decide to write the novel?

VW: About two years into working at the gallery, I met the person who roughly corresponds with Ted. He had all of the wonderful and contagious optimism of a con man, and he convinced me that I should take this new skill of producing a continuous stream of language away from my boss and use it for my own purposes. Seize the means of language production, which was myself! . . . I wanted to set up conditions under which I could produce language in a voice that would be called “my own,” but totally unselfconsciously. I was interested in writing a book because I’d done so much short-form, fragmentary writing at the gallery, and wanted to see how these consumable, fragmentary texts could be layered and accumulated into something more dense and unwieldy.

For readers of …

-

* Chris Kraus

-

* Ben Lerner

-

* Lynne Tillman

-

* Joan Didion

-

* Ottessa Moshfegh

-

* Tao Lin

-

* Wayne Kostenbaum

-

* Alexandra Kleeman

-

* Cecelia Pavón

-

* Kate Zambreno

-

* Natasha Stagg

About the author

About the author

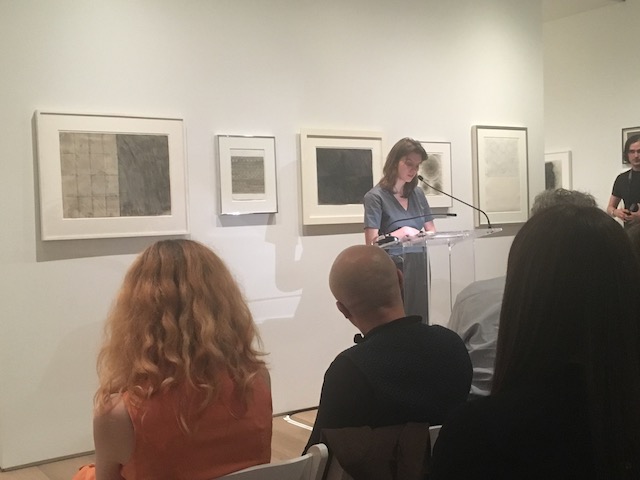

Valerie Werder is a fiction writer, recovering art worker, and doctoral candidate in film and visual studies at Harvard University. Her writing has been published in Public Culture, BOMB, and Flash Art, and performed at Participant Inc, New York, and Artspace New Haven. Werder is a 2023–23 PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program Mentor. She lives in Somerville, Massachusetts with a black cat and hundreds of books.

—Véréna Paravel & Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Valerie Werder

—Aria Dean: There, There; There’s No “There” There by Valerie Werder

—Virgil Abloh "Figures of Speech ICA/BOSTON by Valerie Werder

—"A Notable Fiction" by Valerie Werder is a theatrical performance that critically examines terms of legibility and notability in an online public sphere, asking: does the writing of history always amount to the writing of fiction? "A Notable Fiction" has been performed at Artspace, New Haven, as part of the exhibition "Aliza Shvarts: Off/Scene," and Participant Inc, New York, as part of "A New Job to Unwork At."

`Read Valerie Werder's just -published illustrated "Research Notes" about the writing of Thieves and the weirdness of "the selling game" on Necessary Fiction [necessaryfiction.com].

THIEVES: A Novel by Valerie Werder

An Excerpt from PART II: BUYING

5

. . . Valerie saved the letters and sales pitches she’d been drafting, shut down her computer, and took the elevator to reception, where Sylvie was watering the battery of orchids barricading the reception desk. They were the last to leave the gallery. Sylvie pressed the four-digit code to alarm the building and rushed for the door as the security system counted toward lockdown. It was long past dark.

On the subway downtown, the girls exchanged exhaustions, and by the time they arrived at the bar in Queens, Valerie was mute, skin slack and slick with city scum. She tracked bar-goers’ expressions and gestures without speaking while Sylvie’s eyes grew large and streams of words tumbled out of her mouth. Small islands of bodies congregated around plastic cocktail tables.

Sylvie led Valerie through the crowd on the patio to find their friend, Maria, pushing past solid forms emanating heat through cheap cotton and spandex. Red plastic straws jostled liquor and soda in Valerie’s cup, condensation slurring across her palm. She put her other hand in her pocket to touch the five or six sugar cubes she’d taken from the bar’s condiment tray while the bartender’s back was turned. The cubes’ hard edges softened under her fingers, and she brought hand to nose to smell, but her fingertips didn’t smell like anything but themselves. This dampened her pleasure at getting the cubes without asking for them. She’d have to get rid of them soon, before she was tempted to pop them in her mouth during a lull in conversation. She dropped two on the ground while Sylvie wasn’t looking. With a flick of her wrist, she threw another into a fake terra-cotta planter holding a fake tropical plant. The cube hit the plant’s trunk and bounced across the floor.

Maria was holding a table for them, sober, hoping that an unnamed friend might stop by with coke later in the night. She wore a baseball cap and oversize glasses, and held a cup of seltzer into which she ashed her cigarette over melting ice cubes. She and Sylvie spoke, eyes locked, Maria sliding into Portuguese to complain about the latest frustration at the art magazine she edited, a new editor campaigning for objective and impartial reviews of gallery exhibitions. The last words Valerie caught before the conversation was entirely lost to her were incestuous and roommates. Sylvie responded in brisk Portuguese as Valerie folded her straw into four parts, and then eight, and then sixteen. She did not speak Portuguese, or any language besides English. Valerie set the straw on the patio table where it unfurled like a demented snake.

Techno coursed from the concrete and Sylvie’s smoke intermingled with their visible exhalations in the cold. The scene was external and still, a movie set in service of Maria and Sylvie’s rapid conversation. Valerie screened a film of herself onto the back of her eyelids, trying to concoct an important and well-formed sentence to reintroduce a language she could speak into the conversation. But, when Sylvie paused, polite, and asked, in English, what Valerie was thinking, she didn’t come up with anything to say.

The door to the bar opened and two girls in fake-fur coats and long braids stumbled out, their drinks preceding them onto the patio. Nic, an art critic and part-time gallerist of indeterminate but well-groomed origin, emerged from behind the stumblers and approached Sylvie, putting his arm around her waist and gently moving her to the side by way of greeting. Nic was compact and coolly energetic, with a muscular jaw and wire-rimmed glasses. Maria barely took note of him, turning her attention from the now-occupied Sylvie toward Valerie.

Maria was a quick and brilliant monologist, and Valerie had only to nod whenever she paused, indicating agreement while, in reality, she grew lazy, slouching against the plastic lawn chair, attention occupied almost entirely by the way her jacket rose and fell over her abdomen. Neither Maria nor Sylvie wore clothes that betrayed their bodies, or else they had the kind of neat and self-contained bodies that didn’t announce their digestive functions and breathing patterns. What to do with this bloated sack of organs and thoughts? Valerie fingered the remaining two sugar cubes in her pocket.

Hey, Nic said, eyes fixed upon Maria’s mouth. I know you from somewhere. I remember you. That gap between your teeth. It’s one of the most subtle tooth-gaps I’ve ever seen.

There was no way to respond. Maria frowned at him and turned to Sylvie. I’m going inside for another drink. I’ll catch up with you later.

Walking home, Sylvie told Valerie about a theory she’d developed as Nic shepherded her from table to table. Androids shaped like women are so creepy in sci-fi movies, she said, bony shoulders jutting into Valerie’s as they tripped over the crumbling sidewalk, because they’re not at all committed to their bodies. They know they’ve been fabricated. There’s no pretense that they’re natural, or that their form has any kind of meaning.

Right, an android’s body is pure utility, agreed Valerie, so if she cares about what she looks like, it’s only because she needs to be incognito enough to accomplish her goal. Not because she cares about beauty or cuteness or whatever for its own sake.

You can’t distract a murdering android by saying, “That gap between your teeth is cute”—

Yeah. If she was designed with a tooth-gap, it was probably only so she could distract CIA officers while she stabs them in the kidneys, anyway.

Seriously, what was that with the tooth-gap? The subtle tooth-gap.

I don’t know. Some kind of connoisseurial approach to women, I guess.

Sylvie remembered a college boyfriend who remarked on her tiny ears or feet every time he felt nervous or insecure or bored in arguments. The compliments jolted her from language, reminding her of her hairline, her eye-shape, what her face looked like in the mirror, how her mouth moved when she spoke. The compliments did their job: they rendered her mute. But without Sylvie filling the role of respondent, without her agreements and affirmations and assurances, the boyfriend, too, became unsure of himself, faltered, fell silent. If I were an android designer, I’d make sure to implant the most complex gear in the cutest parts. Like, my android would have super-advanced hearing and recording devices stored in tiny ears.

That’s great. Because tiny ears are both cute and a kind of impediment, right? Like, the CIA officer thinks he’s talking to this regular girl at the bar, tells her he wants to get closer to make sure she can hear him, because she’s got the tiniest, cutest ears.

And that’s how the android gets him. Knife right into the soft part of the skull.

Jesus.

Sorry. I just meant, if anything, she’s happy about her tiny ears. They’re the best disguise.

6

The next morning, Valerie clawed her way out of a disturbed sleep. She was plastered to her mattress in a cocoon of dried sweat and heavy limbs, the night’s dreams struggling to surface and come to a conclusion before the day’s urgent tasks stole them away. In sleep, she, Sylvie, and Maria had been automatons in a New York filled with human men and replicated women. The women were happy to be homogenous. They’d proposed and voted upon the procedure themselves. Valerie and Sylvie discovered, delighted, that they often fell in step due to the identical length and composition of their legs.

The dream began: In a rigidly stratified New York, people could predict each other’s occupations, where they lived, how much money they made, their favorite bars, their fetishes, how often they called their parents, et cetera, with a cursory glance at a name, a face, a hereditary chart. Valerie, for example, could be easily sorted into a genre populated by other twenty-something tote-bag carrying, art-gallery going, suburban-childhood-having humans. Despite the fact that, sociologically speaking, Sylvie, Maria, and Valerie were roughly interchangeable, they found their minor particularities (small ears framed by a tawny crew cut, a charming snaggle tooth, under-eye circles that fluctuated between you look a little sleepy and borderline mauve) being picked out and deployed against them. Similarly, their banal transgressions and neuroses (regular lunches of wine and oyster crackers, only getting off to muscular gay porn, compulsively ignoring accumulating mounds of student debt) were considered deep, shameful secrets, peculiar to them and only them.

Slowly, the three discovered that other genres of professional women felt the same way. Maybe Maria had been sharing stories with an apathetic luxury-car advertiser, or maybe Valerie overheard a conversation at a poetry reading. Regardless of its origin, someone began a group chat, which quickly ballooned to a conversation between hundreds, and then thousands. It was easy to pretend that the group represented the totality of women existing in the world, or maybe in all of eternity, because the message thread was so rapid and continuous. Statements appeared one after another from unrecognized numbers, and Valerie’s guess was as good as anyone’s as to who, precisely, her interlocutors were. (Such naïveté—feigned by Valerie’s subconscious and excused by digital anonymity—is easy to dismiss with a cursory review of the group’s formation: its network exhausted the social contacts of a select set of professional women living in New York, ages twenty-five to sixty, and better represented those who hired house cleaners than those who cleaned houses.)

Around 9 p.m. on a Friday evening, dream-Valerie picked up her phone after a shower and nap to find 637 new message alerts. The thread had recently turned to a museum curator’s anger at being singled out by colleagues for a rather prominent mole under her left eye, and a 917-number proposed that all women in the city do away with their human bodies, implanting themselves instead into mechanized shells.

U know thats not a half-bad idea

They’d really have to come up with new ways to take us down a notch You know they wld come up with ways.

But we’d at least get a few days of reprieve!

Actually, I think someone in the group works in AI at DataLab . . . this

could seriously be possible wtf

really????

Hey, yeah, it’s me that works for DataLab, I’m head of design technology and robotics. My name’s Gretchen.

Valerie opted not to voice an opinion, waiting for the phone numbers of the only two women she knew—Sylvie and Maria— to pop up in the chat. Four minutes later, Maria opined yeah, god, this would be such a relief. Concerns about funding were raised; one member was quite wealthy and assured the rest she’d tap into the usual philanthropic networks. An 845-number wondered how will we get all of the other women in the city, the women who aren’t in the group, on board? A prominent intellectual promised to write an Op Ed in the Times; she’d argue for a beautiful sense of equality, freedom from objectification, release from appearances. A 718-number repeatedly asked what the automated bodies would look like, suggesting maybe we should neutralize race, select an unnatural color, like blue or gray or purple. Members were not sure. Objections were raised, anxieties duly noted. The group would put their collective body’s physical appearance to a vote. On the day of the vote, Maria refused to participate. They’ve got Gretchen from DesignLab making the thing. I know her. It doesn’t matter if it’s gold or magenta or teal. Any automaton made by Gretchen is going to look like Barbarella fell into a vat of Pantone. Indeed, the final design was silver, with a poufy wig and button nose.

Once automated, it was nearly impossible to tell which body belonged to your friend, colleague, girlfriend, ex-girlfriend, and so on. The women didn’t trust each other, and for good reason. After implantation in their silvery new bodies, an initial sense of peace in the city was followed by a great and sudden confusion. Thieving women snuck into homes and workplaces not their own, taking computers and appliances and the like. Identical women emptied one another’s bank accounts, kidnapped those in higher positions to insert themselves by proxy into alternate lives. If you were able to remember a friend’s distinctive walk (flat-footed, slow) or the sour expression she made when she was being insulted—and if you could detect a trace of this gesture on a silvery automaton— you could hazard a guess at the automaton’s identity. Most women, though, were loath to reveal who they were, and even the most idiosyncratic gestures could be imitated by a skilled identity thief.

In a highly publicized case, one woman, a professor, locked up her ex’s new girlfriend and took her place, thinking she’d be able to regain her former paramour’s affections, if only by posing as her new love. The presumed ex, though, turned out to also be an identity thief, a woman with tens of thousands of dollars in credit card debt and medical bills who was squatting in the wealthy ex’s apartment, paying off her loans using the ex’s credit cards. During courtroom proceedings, the identity thief said she’d barely had to do any work to convince the professor that she was, in fact, her former love. She’d looked through bank statements and old receipts, watched a few videos. Easy.

Reporters covering the case found it difficult to transcribe court proceedings, having no way to tell which woman was speaking at any given time. They began to confuse themselves with their interviewees, and lawyers with the criminals, and soon women were speaking in tandem, completing each other’s sentences, infecting each other with the desire to sabotage the entire project. It was a mess. Officials couldn’t determine whether a large majority of women were suddenly participating in criminal activity, or whether a small group of deviants had taken advantage of the new system, mucked it all up. Crime rates tripled, and police were loath to arrest the hard, silvery women. The women in the group were astounded. They had not predicted this.

In the confusion, silvery Valerie wandered around Union Square where, in her previous life, pick-up artists and peddlers approached her while she was eating 50¢ hard-boiled eggs and scrolling through art-world blogs. For several days, she watched an automaton with the mannerisms of Sylvie, who leaned against the fake brick of the Whole Foods, smoking, eyeing groups of Guinean men with glinting black plastic bags, who sang, Louis, Gucci, Hermès, Céline . . . snap ’em up before the police do!

A select few women had escaped the automation decree by faking homelessness, dressing in shapeless men’s clothes and hiding in subway stations smelling of urine, speaking senseless languages or acting otherwise deranged. Of those remaining unautomated, it was, in the end, impossible to tell who had once been a woman and who had not. The silvery Valerie didn’t care. She studied the automaton she assumed was Sylvie as the Sylvie studied the peddlers.

Hey, the Valerie ventured, stepping beside the Sylvie, but not looking at her face. Do you know of a good place to get coffee around here?

The Sylvie looked at her sharply, squinting, not speaking. The Valerie tried again. I like that gap between your teeth.

The Sylvie grabbed her forearm. It’s you.

The two went off in search of Marias, finding several candidates: one who wore a baseball cap and eagerly engaged in exchanges with strangers, which the Sylvie thought suspiciously unlike aloof Maria; another, who sat on stoops and leaned against buildings with the exact comportment the Sylvie knew so well; and a third, combative, who snuck, stealthy, around the city with some sort of plan the two couldn’t quite figure out, marking advertisements and photographing men at random. They stalked these Marias for days.

The Valerie, exhausted and despairing, begged the Sylvie for a break. Maybe a drink, she suggested, or a trip to the Russian bathhouse.

Absolutely not, the Sylvie said. She’d become obsessed with the three Marias, didn’t want to abandon pursuit for even a few hours, fearing that if the two stopped following their targets, other automated women would come in and replace the Marias, kidnap or hide or kill the Marias, and the Valerie and the Sylvie would be none the wiser. After much persuasion, the Sylvie finally agreed to an hour in the steam room, advising against intoxication of any form in the current political climate. The two women walked to the baths on St. Marks, took towels from the hairy and potbellied attendant, and undressed.

A thick cloud of steam obscured the women’s vision, and the Valerie and the Sylvie were barely able to see their own knees through the dull white vapor. The two sat side-by-side, silent, and the Valerie watched in confused amazement as shapes grew on her legs: a heat rash.

Are you embarrassed to be naked? the Sylvie asked, frowning. No, the Valerie replied, it’s just a rash.

I thought maybe you were blushing.

The Valerie considered this. The body wasn’t really hers. It was the same as the Sylvie’s, the same as all the others. Could she be ashamed of something so stupidly repetitive?

Look, it’s happening to me, too. The Sylvie pressed at her thighs, marking bluish splotches in the middle of gray, her rash extending from knees to thighs.

Creepy. The Valerie poked at her thigh, and then the Sylvie’s. Their rashes were different. Let’s get out of here.

No, wait. The Sylvie paused. We have to remember the patterns. We’ll come back tomorrow and see if they’re the same, and, if they are, we can recognize each other, test who we’re talking to, make sure you’re always you, Maria is always Maria. Once we find her. If we find her.

But do you really want to be able to tell? the Valerie began to ask, standing up, the room spinning, light filtering in through the steam—and then the dream was distinct from Valerie, splintered off from her body and incompatible with the reality in which she found herself. She was awake.

On an evening run through a Hasidic section of East Williamsburg a few days later, she realized that the dream-automaton-Sylvie may have been trying to sabotage her, but she had no way of accessing the dream version of herself to warn her.

7

It is necessary to establish here that it is by design that the two halves of Valerie cannot communicate with each other. A pair, after all, can’t coexist peaceably. Put side by side, Valerie learned in chemistry, or maybe psychology, two will tend to establish a hierarchy: sleepy-and-sneaky Valerie trying to trick waking-Valerie, waking-Valerie oppressing her psychic twin. It’s necessary that they be kept at a distance, that they communicate only across the thin neural veil that distinguishes sleep from waking. In this way, they can neither cohere nor compete, although they sometimes overlap, merge and entangle, only to separate and repel each other once again. Which one can claim ownership of the name they share? Who is the rightful protagonist of this story? Both are doomed to fail at this task, this senseless contest for possession of Valerie.