One image is always more than one image — Gerald Murnane

Things don’t connect, they correspond — Jack Spicer

PART THREE

And then came the arrests. Came the tear gas, the percussion grenades, the pepper spray, the wooden bullets, the LRAD declaration of unlawful assembly, the kettling and the batons, came the bicycle scouts having returned from recon to sound the alarm, into the sidestreets, over the fence, be like water, the mad rush of those escaping and those holding the line, shields to the front, came the unmarked vans, the snatch and grab and the zip ties, the whole fucking apparatus, came the smoke from the fire inside the museum gift shop, came the press in vans and copters, cameras and shouting and bodies on the ground, came the long and banal processing and waiting, the phone swipes and the mugshot jokes, the adrenaline withdrawals and the passing of empty water bottles to piss in or extra masks for the tear gas residue on clothes, settling in for the long night…

But also this — came the legal observers moving in to take names and birthdates, came the unbloccing and the regroup, came the jail support crews springing into action, came the bail funds and the court dates, the visits to and queuing at the courthouse next to the museum, now boarded up and fenced-off, came the social media posts, came the debriefs and the shared wound-licking and celebratory whatnexts, came the waiting for the crackdown, the online surveillance, the doxxing, came the next day and the next night and the next day and the next…

≡ ≡ ≡

And so then — returning home, greeting the anxious dog, stripping down and dumping everything immediately into the washer, discarding contact lenses and running water over the eyeballs, reassuring the dog once more, the projector lights having burned out or the dog having pawed the laptop shut, conditioned to associate the closing clicking sound with her human’s shift of attention to things in the world such as sweet patient dog, sitting in the dark together then, turning the phone on and scrolling through the photos with one hand, the other stroking the dog’s soft ears, finding nothing but overexposed closeups of a dark purple sun, ablaze against an orange sky, or a brown sun over a green sea or a red mountain thrusting out of a yellow sea, or sharp blue-black lines moving back and forth, batons against the sky, the screen refusing to settle into any semblance of clear focus or representational precision, pixels dancing in artificial light, glyphs and sigils and static and glitch in the transmissions, memory adrift in correspondences between retina-mind and havingseen and languaging it all to oneself, events recalled in anything but tranquility, the phone then-now burning hot in the hand, vibrating with messages from within, the screen now locked and filled with an accretion of laughing-crying emojis.

(But also this — Etel, in an interview: “The signs are there as an excess of emotion. The signs are the unsaid. More can be said but you are stopped by your emotion.”

≡ ≡ ≡

But also this — waiting, waiting for updates from the lawyers, notices from the state, news from beneath the news, prepping for court, recalling the scene in Marleen Gorris’s film A Question of Silence, where at the murder trial of three women, who not previously knowing each other had spontaneously attacked and killed a male shopkeeper in front of other women shoppers, the witnesses showing up in court each day in silent soldiarity, the liberal feminist defense lawyer trying to coax from each defendant some biographical narrative that might help explain and thus extenuate such violence in the language of the Law, each defendant resisting, retreating into silence or exploding into laughter and idle gossip, then-now in the courtroom the defendants exploding into rigorous laughter, at the all-male judges, at the convention of their questions, at the Law itself, the sister-witnesses then joining the laughter, laughter that breaks the spell of the Law and its reified rituals, laughter that refuses to take serious any public reckoning unable and unwilling to understand why any woman might at any moment choose to murder any man, even for “no good reason,” a laughing-crying excess of emotion that disrupts the logics of the Law.

≡ ≡ ≡

And also this then — being spurred to remember a courtroom scene in an episode of the Canadian television series Trailer Park Boys, where Ricky, having fired his courtappointed defense attorney, finds himself unable to defend himself against a charge of stealing and reselling gasoline — having set up an ersatz capitalist enterprise of appropriation and redistribution for profit — when he is told he can’t swear or smoke in the courtroom. After several attempts to complete his sentences, each cut short as he reaches a curse word, and after the prosecutor belittles his intelligence, Ricky stands to address the judge:

“Look, I can’t speak without swearing, and I’ve only got my grade ten, and I haven’t had a cigarette since I’ve been arrested, and I’m ready to fuckin’ snap. So I’d like to make a request under the … People’s Freedom of Choices and Voices Act that I be able to smoke and swear in the courtroom. Cuz if I can’t smoke and swear, I’m fucked, and so are all these guys. I won’t be able to properly express myself at a court level and that’s bullshit. It’s not fair and if you asked me I think it’s a fuckin’ mistrial.”

Ricky thus reveals the Law to be fundamentally inaccessible to those who refuse or are unable to live within its juridical or linguistic strictures. Perhaps only because it is after all a comedy series requiring the suspension of disbelief in order to push its plot forward, the judge allows Ricky to defend himself in his own manner. After which he proceeds, “My first order of business is to tell the prosecutor to shut the fuck up and wipe that stupid fuckin’ grin off his face cuz it’s distractilating my case.”

Ricky, who viewers of the show know is despite his other challenges incredibly adept at talking his way out of trouble, a bullshit artist par excellance, proceeds to win the case.

≡ ≡ ≡

But also this — Zora Neale Hurston’s “The Conscience of the Court,” a story of a black woman named Laura Lee Kimble who defends herself in court against a charge of assaulting a white man (for which she has already spent three weeks in jail). After declining the offer of a public defender, she proceeds to narrate the events in her own telling, her own vernacular, which moves the white judge to perceive the injustice in the charges and instruct the jury to deliver a verdict of not-guilty.

But also this — having discussed the story in a prison classroom, focused on the question of defending oneself in one’s own language, students then sharing their disbelief at Hurston’s naivete in imagining a white judge would be so understanding, or critiquing the way the story relies on the empathy of well-meaning white men to forestall injustice through the means of the “fair trial,” such that readers’ faith in the justice system not be shaken. At the same time, all agreeing that the only reason Ms. Kimble had even a chance is that she had declined the offer of a public defender — saying, “I don’t reckon it would do me a bit of good.” Indeed, if the story had any lasting merits for the students it was in demonstrating, in line with their own experiences, how the public defender system only worked to reaffirm the legitimacy of the Law through forms of language that remain inaccessible to too many.

≡ ≡ ≡

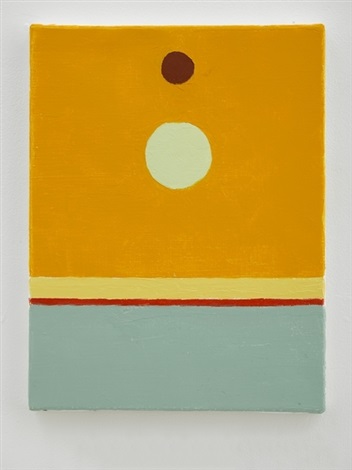

But also this — having received news of a student’s death from Covid, to recall again the prison classroom, a memory-image in the mind revealing itself here-now within the writing about the discussing and the writing-remembering now about having seen: on the far wall, an old poster advertising travel to some European country, a pale yellow sun floating above a seascape rendered in what looks like colored pencil, the corners of the poster wilting and bent, held up by peeling tape, the faded image of that faraway sun in contrast to the artificial light in the windowless room, piercing through the structural conditions of prison education itself, its enlightenment ideology of education as both reformative and disciplinary.

And also this — Etel writing in 1968, in “A Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut”:

In the beginning was San Quentin

I saw it at twilight a gigantic casino

a Frank Lloyd Wright building a

floating dream but

it was rejecting light

like a mirror

its sadness all written in the refusal

light was not going through

it was being arrested in all its glory

the prison transfigured, only for

those outside

the inmates remaining in the dark

and these images are imprisoned on

paper

I see them struggle toward freedom,

toward meaning

≡ ≡ ≡

And so also this — remembering this poster, or rather, seeing it then-now as a memory-image, immediately recalling a scene, or more precisely a sentence capturing a scene, having appeared — whatever appeared means — in one of filmmaker and writer Edgardo Cozarinsky’s essay-stories (or postcards, as the author calls them, as if to foreground the frozen-image effect of memories of having-been-elsewhere, the writing a time-stamp of that having-been-there-then), where in the text coming upon a similar sun-soaked travel poster produces a punctum through the veil of the narrator’s worldview on a date and location given with such precision as to suggest true revelation and import.

So then also — walking to the bookshelf and finding Urban Voodoo, paging through and realizing that the travel poster had been but a mental image fused out of two separate sentences in two separate prose pieces, so that this —

I remember how, on the 18th of April 1974, between the Tribunales and Callo stations of the Buenos Aires subway, the fundamental hypocrisy of all ideological operations became apparent to me.

corresponded in the reading-memory to —

Each society dreams its doom, and the sun is that ill-defined circle of oily yellow among chemical greens and oranges, printed on paper and pasted on the walls of the Stockholm subway.

And so then — to input “April 18, 1974 Buenos Aires” into a search image as if one might find an image of a long-lost travel poster, now perhaps if only in the imagination affixed to the wall of the prison classroom, finding instead mention of a US loan of $100m to Argentina approved on that day, with interest rates 1.5% higher than comparable European loans, then realizing that Cozarinsky’s realization on that day may have been in response to reading that day’s news which of course would recount the news of April 17 instead, a day on which Nixon and Kissinger spoke by telephone and agreed to quietly allow American-owned auto companies based in Argentina to sell to Cuba, then-now clicking link after link as if each underlined key-phrase was shouting “But also this —” until arriving at — whatever arrival is — a newspaper photograph of Etel Adnan, standing in front of a painting made in 1974, its yellow sun hovering over a landscape of green and orange.

≡ ≡ ≡

And so then — Etel having written: “A yellow sun in my memory cancer in the heart of the rose the prisoner’s cry.” Having committed to memory such a sentence and then-now taking its measure when-while typing it here. The subway train emerging from the ground and screeching into the air, a blockade at the gates of the prison.

But also this — an ill-defined yellow circle, spray painted onto a wooden surface over a blood-rust background, a sequence of counter-placards with which to exert pressure in the duration of shared exhortation and spatial battle, minor wars of maneuver and position. Somehow then-now corresponding to a list of future court dates fusing calendric temporality with the time-work of having committed to memory various concepts of justice — whatever justice is — while deciding what to wear to the courthouse next to the fenced and still-expanding museum. The sun blotted out by smoke and ash and numberless drones, birds flying through fog across the bay.

But also this — to live and think and feel with Etel’s writing and art being at times enough though never enough — whatever enough is. Outside bombs continuing to fall from the sky, even if far away and out of the dog’s human’s earshot, knowing this even if only imagining it or imagining making it so by writing it down, the dog dreaming of a red-meat sun at the foot of the bed. “While drinking coffee I am in the midst of the Gulf War,” wrote Etel. How to narrate in conventional syntax the duration of living in-with such sequences of living-through.

And so then — to test the following proposition by means of composing it in conventional syntax and placing it here-now: that art changes little but is sufficient reason to continue living. The ash-covered laptop having been powered down, lines of Etel’s resonating in the mind’s ear, shadows pressing in, the law outside waiting. Either the dog or her human opening their mouth as if to make sound. A blood-orange sun sears through the night.

≡ ≡ ≡

≡ ≡ ≡

POSTSCRIPT

November 14, 2021

Having received the news, walking then downtown to the museum, through misted and sepulchral streets, the buzz of industrial light fixtures reverberating out from a vacant high-end apartment complex, the dog tugging on its leash to sniff at a box of discarded and ash-covered potatoes, one foot then another foot, each block an empty measure, time unhinged from forward movement, a full stop that doesn’t stop. People gathering outside the museum, now sheathed at street level in a makeshift institutional barricade of fencing and tarpaulin, a bronze hand having been severed from the statue lying on the ground, gesturing toward the neighboring courthouse where tomorrow would begin the hearings, there having been spray painted across the museum façade a line of Etel’s: “I would rather see a river than a museum.”

And also this — an expanding silence in the growing crowd, a palpable and spacious quiet, to be within and among. The sun scorching the other side of the world while being here in such candlelit night. In the mind an image, a thick powder’d line, a greywhite gash spreading down a tree-filled hillside. But also this — the silence in that now-here of no future becoming a kind of chorus, a swell of bodies being there together, resilient and ready to live on, no need to language such knowing-feeling.

And then came the light. Appearing on the museum’s upper façade, as if projected from some unknown source, a floating image of one of Etel’s final paintings, cast through the night and the fog and the particulate matter and the fence, yet with no shadow or hindrance to each ray of light, each microscopic beam of color, the image as if hovering in front of the museum, not touching it or any other surface, and then slowing expanding, rising up into the night sky, a pale red moon an endless green sea a blue-brown mountain and shapes and colors and forms and lines slowly spreading and dissolving into pure light cast into the cosmos beyond the reach of still living still human sight.

David Buuck lives in Oakland, CA. He is the co-founder and editor of Tripwire, a journal of poetics (tripwirejournal.com), and founder of BARGE, the Bay Area Research Group in Enviro-aesthetics. Recent books include Noise in the Face of (Roof Books 2016), SITE CITE CITY (Futurepoem, 2015) and An Army of Lovers, co-written with Juliana Spahr (City Lights, 2013), along with the chapbook The Riotous Outside (Commune Editions, 2018). He teaches at Mills College, where he is the chief steward of the adjunct faculty union, and at San Quentin's Prison University Program, and is the Academic Director of the Clemente Course in the Humanities at Oakland Adult Career Education.

More work by Etel Adnan and discussion of her painting and poetry can be found at Mass MOCA, at Flash Art, at Jacket2 (on her poem The Arab Apocalypse), and at The Guggenheim Museum, as well as many other locales online.