Deep Tissue

Two housesits in Hudson, NY; two mysterious scratch marks; two bats; two cats; two multimedia art installations; two concerts at Knockdown Center in Queens; and a second interview with Xiu Xiu’s Jamie Stewart.

* * *

I walk to the cemetery, write a name down on paper, and listen.

I listen as I drive to a grocery store 15 miles away.

I ride in a friend’s truck, inspect his wedding band, and listen.

I listen while brushing my teeth. A bat is asleep. The bathroom is maritime-themed.

I listen while chopping purple vegetables, which scares the oversized Maine Coon.

I kiss her ear. Does it listen?

I become a table and am murdered by a weasel.

chicken run / confused it runs / chicken run / in course confused

chicken run / bloodletting / some / untried / left over

chicken run / confused it runs / chicken run

/ heartbreak.

Amphetamine salts listen as the spigot pours.

The treadmill listens as I run.

The deeper the love, the more quickly it runs.

—Hi.

—Hey, how are you doing?

—Is this working?

—I can hear you.

—Do you want to use video?

—We can talk like normal prehistoric people.

[a bird cries]

—That’s a sound.

—That’s my home.

Jamie Stewart is writing a book about childhood abuse and adult sexual misadventures. I am writing a book about cracking eggs into a bowl until I find a double yolk. The double yolk, I imagine, will be my Lucky 7. In September, I crack two eggs and get two double yolks in a row. Online, I read this doubling is a sign of good luck—or is it simply indicative of a hen who overlabored? Jamie Stewart is vegan and thus does not eat eggs. I have not read Anything That Moves, the book he is writing, but over the summer, I made a commitment to write about it for Fence. The former sentence may include a lie: I may have read a few excerpts from Anything That Moves on the Internet. One possible excerpt was a blog post archived on someone else’s blog, though I’m not sure whether the blog post was actually an excerpt and, if it was an excerpt, whether or not it will be included in the final draft of the book, which is in the process of being re-written. The other possible excerpts I read were articles by Stewart at The Huffington Post about the myriad sexual possibilities that accompany bisexual masculinity and the bigotry he experienced while living in Durham, North Carolina. Both articles are cheeky, intelligent, constellatory. I read them just after our interview on August 5, 2021. 11 days later, on August 16, 2021, I was sexually assaulted throughout the duration of a massage administered by a generically named man practicing bodywork without a registered license at a bourgeois day spa in upstate New York.

It felt stupid to write that last sentence: shame lurks beneath its surface.

Did you do something to make that happen?

—So you said you have about an hour, because you have a dentist appointment?

—Give or take. Maybe slightly less than that. But about that long.

—Okay, I’ll dive in. First, however, the reason why this turned into two separate pieces is because I pitched this to two places. I thought only one would take it. I think the Fence piece for which we’re speaking now will probably be more robust and lyrical or experimental in form, and the other one will be more standard music journalism. Just so you know what you’re stepping into.

—That sounds good.

—So I read about your book. I didn’t spend time with the audiobook because I didn’t know it existed and thought I would be reading an ARC, and now the audiobook no longer exists. So I’m curious to talk about where you are in terms of the revision process.

Like cracking an egg with a double, August can be split in two: before and after. Half and half. During the first half of the month, I drove to the grocery store, parked the car, opened the door, and walked through every aisle alone. Touching containers of vegetable broth, I felt haunted by the past year of self-destructive, risky sexual behaviors, which had recently landed me at a doctor’s office, and subsequently at the Baltimore Medical Examiner’s Office, where I studied Frances Glessner Lee’s dollhouse-style murder dioramas The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death and also encountered several objects contained behind glass labeled VARIOUS PARAPHERNALIA THAT CAN BE FOUND AT THE SCENE OF AN AUTOEROTIC DEATH: a belt; a lock and key; a pair of knee highs; rope; a pair of handcuffs. Looking at these objects, I envisioned my body on a Tilt-a-Whirl, then remembered a black and white photograph I took in Prospect Park of a plastic bottle floating in an algae bloom: two suffocating forces floating atop the surface of a lake.

During the month’s latter half, I became hyper-vigilantly aware of everybody in the grocery store: a man selecting a KIND bar; a man with a NASCAR shirt; a man stocking margarine. In their presence, my thoracic spine tightened. This same phenomenon occurred as I walked up and down the street, as I withdrew money from an ATM, and as I exchanged weights with strangers at the gym. Here, there is something to be said about the nervous system, the body protecting itself via an ensconced register of fear, and how, in the aftermath of trauma, the thoracic spine no longer understands it’s safe because it’s not.

— I started … I guess I probably finished it about .... let me see. Let me start over. [pause] A person who has since become my friend, Sam Nicholson, came up to me at a show in New York a few years ago. He had been coming to Xiu Xiu shows for a long time. Now he works in the publishing industry. He asked me if I was interested in writing a book. And I said that I could write haikus but I’d never really written anything other than that. That person works at a very big publishing house, and I said that I assumed they wouldn’t be interested in that. And he said no, they probably wouldn’t. But I kept his card and thought about it for a couple months, and there was kind of a long list of quote-unquote stories that I would think about and tell people when I was drunk that all generally had to do with kind of negative sexual misadventures, and generally they were funny. Hopefully. But there was always a tinge of discombobulation and depression attached to them. So I asked him if he’d be interested in something like that and he said to write him a couple of passages. Never having written a novel before—I deal with songs which are all in a short form—I was thinking of Drown by Junot Diaz and House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. Both are organized in vignettes. The narratives are not really linear narratives; rather, the vignettes all relate to each other in tone. The approach is different from short stories. You can read each vignette as if it were its own piece, but as a group they all link together. And I thought I could possibly try that as a form. So I sent him five or six things like that, and he told me to keep going with it. And then I probably finished that a couple years ago, and then he kind of disappeared, and I wondered what was going on. I couldn’t get a hold of him at all. And I thought well, okay, this happens in the music business all the time. People ask you to do stuff, and they stop paying attention to you, so I thought it might be similar. And I thought, well, I’ll just put it out as an audio book myself—no big deal. And then a few months ago I heard back from him, and he told me that he was having some health problems, and that’s why I hadn’t heard from him. And then he set me up with an agent, Ian Bonaparte, and I sent him what I had worked on, and the agent gave me some very insightful notes as to things that could be added and taken away. So I’m in the process of doing that right now. It’s not entirely rewriting it, but adding a couple of dimensions to the stories. And I guess in some ways adding a layer of not necessarily retrospection but kind of a small amount of narration on the consequences of some of these things. It’s in no way meant to be redemptive. It’s not like a recovery story or anything like that. A bunch of stupid and bad things happened, and there were stupid and bad results, and that’s the end. But anyway, so I’m probably about ⅔ of the way done with the rewrite. It seems like a couple of legit places might be interested in it, so it could get turned into something real. But we’ll see.

It is August 17, 2021, and I am alone in the borrowed sports car I re-taught myself to drive, watching the sky turn pink. It feels good to be locked in it. I am not an open cage. As I think this thought, The Air Force plays. I am or was eating popcorn while doing research for my writing, both for an essay I already wrote or am perhaps now writing again. Per usual, I will write dozens of pages to figure out what I think. How do I write an essay about a book I haven’t read? It is a peculiar challenge. The other records I listen to in the car are called Knife Play, Forget, Nina, OH NO, Fabulous Muscles, Women as Lovers, La Forêt, Fag Patrol, A Promise. There are others. And there are so many songs. I construct a playlist to deconstruct them.

Listening to the aforementioned playlist, I try to discern how to write the essay I said I would write about Anything That Moves. Suddenly, I am standing on my own legs. Do I possess two or four? It is no longer August. Writing this, I am working very hard to not detach from a certain part of myself. By which I mean I feel as if a hull has broken. There is no more frame. Everything has fallen away. At once, I envision myself naked in a snow-globe, glued to a plinth and looking outside from within. As snow falls on my miniature simulacrum self, I feel certain of several things: I want to write the essay; I am actively thinking about it even when it seems I am not thinking about it; I have recorded and transcribed an interview for it; I care about its author’s well-being and art practice. I want to do a good job. But now that I inhabit a snow-globe, it feels impossible to find the right words with which to write an essay about a book I have not read about childhood abuse and sexual misadventures. The subjects resonate, but life’s context overwhelms.

—Listening to some of your other interviews and hearing you talk about this almost, like, monastic scheduling of your life. I wondered, is there meditation in here? Is this lifestyle monastery-inspired?

—When I’m not as busy—when the monastic schedule’s not as full—there is. I should try to make enough time in the day.

—Have you been to a monastery?

—No, have you?

It is August 2021, and I am temporarily living in Hudson, New York. Five years ago, I took care of this house and had a nervous breakdown. This go-around, I am adept at being alone and neither hate nor blame myself—nor physically injure myself—for my most vulnerable attributes. I reflect on the passage of time while grooming an oversized Maine Coon, watering trees, reading a friend’s book about utopia, picking wildflowers, walking through a cemetery with crumbling tombstones in it, and writing the phrase OBJECT PERMANENCE on shirts with fabric markers. Each morning, I sit on the floor and do nothing. Each night, I eat dinner with an old friend who lives in town.

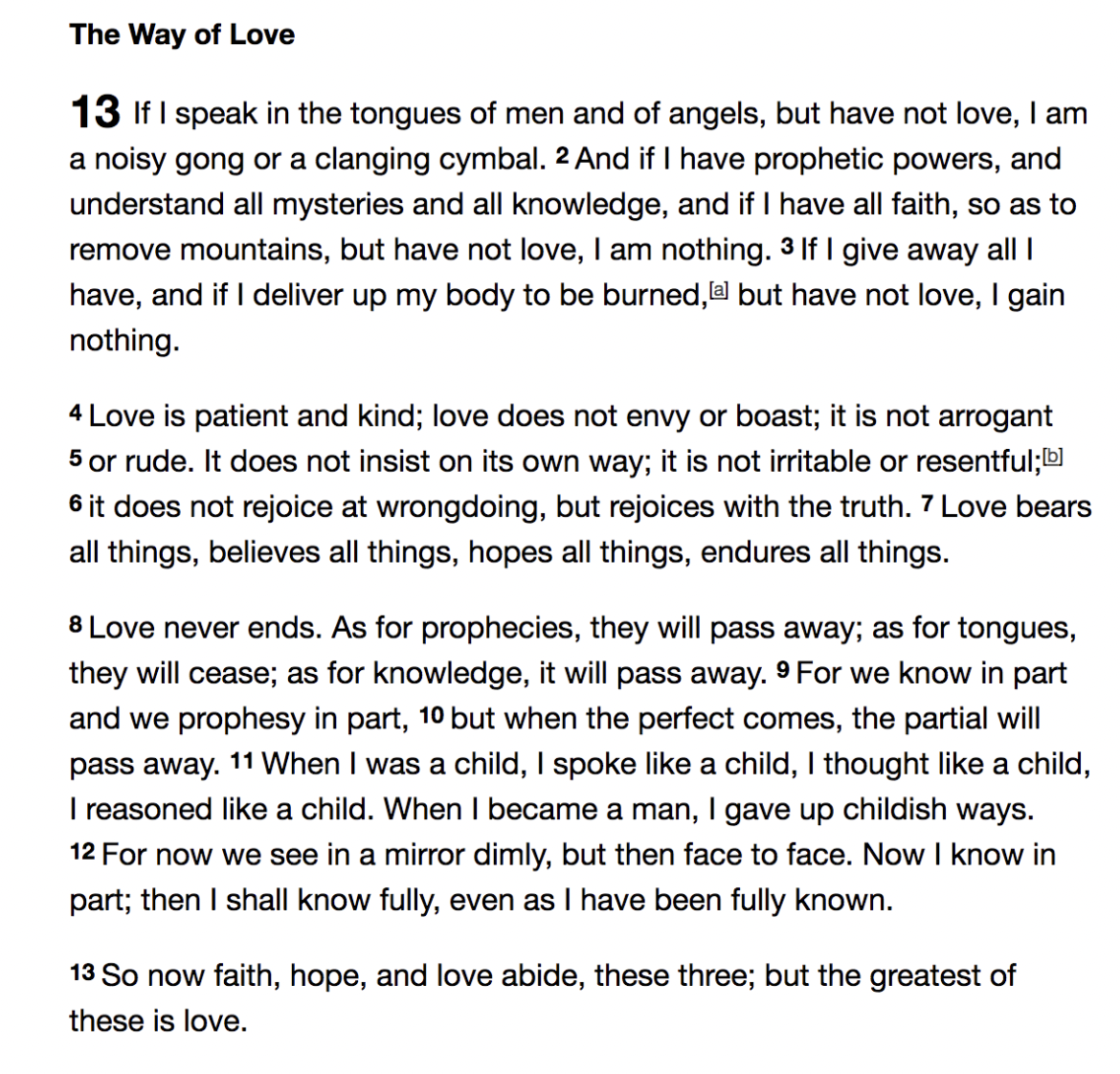

In Hudson, I finish memorizing 1 Corinthians 13, a process I started in Brooklyn. I recite the Bible verse aloud at the end of my daily Zazen practice, following my Buddhist-Quaker-Catholic loving-kindness litany. 1 Corinthians 13 is the Bible verse about love heterosexual Christian couples like to recite at weddings. The why of this Christian matrimonial curatorial decisionmaking makes clear sense to me: 1 Corinthians 13 is an astonishingly moving Bible passage. I began to feel it alchemize my body as my mind integrated it. At first, its language made me weep. Now that I have grieved something unknown, 1 Corinthians 13 feels comforting and innate:

“Love begins and love ends.” So are the lyrics to “PJ In the Streets...” from Xiu Xiu’s The Air Force. The record’s cover depicts Christ Crowned with Thorns, an Italian Renaissance tempera and gold leaf painting by Fra Angelico (1438-1439). The painter, a Dominican friar, purportedly wept as he painted his divine subjects. As I consider this lyric from “PJ in the Streets…,” I pose questions: Does real love end? Or is that which we frequently call love an imaginary, a fake? If we’re deluded by imaginary love, what deludes us? Do our own doomed repetitions serve as spectacles propping up the turbulence of our lives to which we’ve grown accustomed? And if real love is endless, per 1 Corinthians 13, what does forever feel like?

In the car, I am or was eating popcorn emblazoned with a cartoon Buddha, the religious deity who abandoned his wife and child to seek enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. I resent the Buddha’s story but miss the mise-en-scène of Zen Mountain Monastery, where I sat interminable sesshins before the world shut down. A monastery is quiet; the mind is very loud. In the grocery store, I opt for self-checkout so I don’t have to speak. It is or was a hot day. The car where I am or was eating popcorn is a sports car I was borrowing that I did not know was opulent. I don’t care much for cars. They have four wheels and are made of metal. I recently wrote the introduction to a book published by Fence about a car killing my friend. I have not driven since.

—I have two different [meditation practices]. One is spiritually based, and one is more physically based. I had an unusual religious upbringing. My mom grew up an athiest but became religious after she had children, and my dad grew up a hardcore Catholic, and as people who grow up in hardcore Catholic environments often do, he turned away from that as he got older, and he became interested in… He was a hippie, so Eastern types of philosophy. I did not have a good childhood, but one thing that my parents did was that they set spirituality and religion out for us as an option to find some refuge in. It was never something that was compulsory, but it was something that could be turned to in whatever form made some kind of sense. And for that reason, spirituality is something that has remained a positive part of my life. But because it was amorphous, my quote-unquote practice is also fairly amorphous. There was a period where my dad and I were both going to this quasi-Hindu Christian church called Ananda. A lot of my meditation practice and spirituality is based on some things that I learned there. This was a long time ago—in my early 20s. But it stuck with me. [Ananda promotes] a very open conception about what god could possibly be, or not be. It’s borderline agnosticism, but I sort of … I guess the idea is to basically have no idea what’s going on, but to believe there is possibly something going on, and feel contentment in not-knowing. The other [meditation practice] is just to calm down when I’m stressing out. I had this one therapist who said, “Breathe in on the syllable ‘re,’ breathe out on the syllable ‘lax.’ Re-lax, relax.” It’s actually really good. It distracts me from whatever’s going on. I’m surprised at how effective it is. And anytime I’m doing any sort of spiritually-based meditation, I sometimes feel a certain amount of pressure to do it right. Which is just me. I know it has nothing to do with any positive spirits that are floating around.

In Hudson, a bat arrives—or is it a bird? It comes at night while I am sleeping, a few days after I conduct my interview for this essay, but before August 16th, the day I become a table. I hear the bat’s wings flutter, circumnavigating my sleep, and at first I think it is the oversized Maine Coon cat for whose well-being I am currently responsible.

I am afraid of the bat, whose dark, quick, frenetic presence activates my fight-or-flight response. The morning of its appearance, I flee to the couch at 5:00am and research so-called pests. Despite the fact these animals are not inherently vexing, language renders them as such. And although my fantasy has always been that I’m a rigorous critical thinker and lover of animals, I am leaving messages on pest control services’ voicemail systems and chatting with strangers on message boards about how to rid the house of this creature.

This is not my first time encountering a bat. The other time was in Fall 2019 at Zen Mountain Monastery, during an aforementioned sesshin retreat. Upon returning home from the retreat, I wrote:

During a silent meditation retreat, I was washing a window when a bat flew in. I screamed—something everyone wants to do during a silent meditation retreat. Was the bat a living bat, or a dead rat? Its body descended onto the floor.

I placed a garbage can atop the creature—a living bat, not a dead rat—and found the monk who finds me when I hide.

This is a moment in which to note there are three characters in this story. These characters are also thoughts: the living bat, the monk, and Claire.

The monk lifted the garbage can from atop the living bat and took the bat into his palms. “It's okay,” the monk said to the bat. He opened the window. “Be careful with your little wing,” he said.

The monk gently placed the bat onto the windowsill. My anxiety continued to loom. For weeks, I continued to think about this interaction: the bat as a thought in need; the monk as a model of care, tenderness, soothing, stillness amidst fear. A new way to think.

After I finished cleaning the window, I taped a sign to it: A bat lives outside this window. Please proceed with care.

The night after the bat arrives, a friend spends the night. We chase the bat with a broom. The bat can hear, but it can’t see. Then another friend comes to town and spends the night too, though this occasion is unplanned. He is married and wears a wedding band. This is prior to August 16, 2021. I spend most of my other nights with the oversized Maine Coon, Noodle. It is simple to wake up with her. She makes biscuits on my chest and never fails to show affection.

I will always be nicer to the cat than I am to you is a lyric on a Xiu Xiu record called Dear God, I Hate Myself, reissued by Kill Rock Stars at the end of July. I think about this lyric a lot because it speaks to my participation in a life partnership circa 2010, in which I did not know how to be alone and therefore couldn’t be together. Meanwhile, the house for which I am sitting, owned by a pair of married architects, is decorated with twin flame ephemera.

All good things happen in twos. All bad things are split in two, too.

Why are there always two of everything, I ask.

Why are there always two?

—There are two authors whom I’ve re-read. Maybe ten years ago I was obsessed with [Yukio] Mishima. The same thing with Elfriede Jelinek. I might try to re-read her again. And it’s very corny for any sort of, like, white artsy person to say, but I re-read Cormac McCarthy a lot.

—I thought you were going to say Infinite Jest.

[laughter]

—The darkness and extraordinary turns of phrase never does not give me pause when I read them. And Edward P. Jones I read and re-read a lot. He hasn’t written that many books, but … this is corny also, but they’re just remarkably beautiful. It’s an astounding level of insight and delicacy to them, and subtlety also, which is the opposite of Cormac McCarthy. Those are probably the only two people I’ve been lately reading and re-reading. Oh, there’s this book of Werner Herzog interviews—he just gives an interview about every movie he’s ever did. It’s called Herzog on Herzog. And there’s a David Lynch book called Lynch on Lynch. They just talk about the process of making all of their works. I’ve re-read those a few times, whenever I feel stuck. They’re inspiration totems for me when I’m feeling stuck. They’ve persevered and not quit.

—Do you read poetry?

—I read haikus. I really love Ingeborg Bachmann. I read her a bit. My bandmate Angela got me into her. I guess I re-read Joyce Carol Oates also. The tetralogy she did … I forget what it’s called. I reread that twice. I went through a period last year of reading a lot of … I got a couple volumes of Victorian poetry. I’d never read anything like that at all. I was pleasantly taken. They stand the test of time for a reason.

—What haiku would you recommend to people?

—There’s one volume called Japanese Death Poems which, speaking of Zen, is a volume of the last number of haiku that a number of different monks wrote right before they died. I can’t remember the term for it, but there’s a term for that specific type of haiku, your last thoughts before you die. Otherwise, just all the really typical superstars from Japan from 300 years ago: a lot of modern haiku I think is kind of lame, but I would recommend going to the source. If anybody reads haiku, this is like saying your favorite band is the Beatles, but there’s a guy named Basho. He’s the Beatles of haiku.

It is a few days before the so-called massage therapist—in October, my psychoanalyst points out how I keep calling this man a massage therapist, as if he is a licensed professional, which he is not—transforms me into a table. He has a generic male name, and as I walk to the spa, I think to myself, I hope he’s not a creep. The thought is prescient. In the waiting area, I drink a glass of water and stare at my bare feet.

/

On the recommendation of one of my psychotherapists—I have two; they are different and know about each other; one went on tour with Xiu Xiu 10 years ago—I use New York State’s Office of the Professions database to look up the generically named man I keep calling a massage therapist. Unsurprisingly, I learn he was unlicensed at the time of the assault. Although he has already lost his job at the bourgeois spa, I decide to move forward with filing a state-level complaint. I make this decision following ample reflection and the encouragement of other people. Subsequently, in late October, when I am recounting what happened for a New York State prosecutor, I am asked to indicate whether I was lying face down on the table, and to re-describe the entire experience in specific detail.

The table has turned: I am now the interviewee. Despite the fact the prosecutor represents my case, a power dynamic is at play. I am afraid I will be perceived by him as not telling the truth; I feel self-conscious and thereby want to control how I am perceived; I don’t want to come off as controlling because I don’t regard myself as a controlling person. And I want to tell the truth and do, but my emotions flare, my words fragment, my narrative breaks. Yes, I have had myriad massages by male massage therapists, I say. At home, I get bodywork at least once a week. And how can you lie down on yourself, I want to ask. But the prosecutor does not understand that I am now a table! So instead, I pose the following question: When he is contacted by the state, will the generically named man have access to my full name?

We will need to use your full name in case he gets cute with us, he tells me. To jog his memory.

—Do you have any favorite children’s books?

—My mom was really good about that, and my dad was in the music business and they were hippies, so a lot of their friends were involved in music or the arts and crafts movement, or were writers also. And when I was quite young, I was into Dungeons and Dragons and was reading a bunch of dwarfs and swords kind of books. But when I was in the 5th grade, my mom—it’s a classic—gave me Catcher in the Rye.

—That’s an early age to get Catcher in the Rye.

—It was pretty young. But she gave it to me as part of a series of books about young people in chaos. One was Catcher in the Rye, the other was LOTF, and this other one was Butterfly Revolution, which is sort of like Lord of the Flies. And no one really prompted me to read them, but I think—I don’t know if it was a matter of shutting things out, but I felt quite possessed to read them. I remember reading them in class a few times, and my teacher telling me to stop reading them. A couple years after that, I think a friend of my mom’s gave me ten novels by John Steinbeck. And I felt because I had them and because she was an interesting person I obligatorily went through all of them. Come to think of it, I have read Grapes of Wrath a couple of times. And often make jokes about John …?

—Oh and then—this is so dorky—my mom got me some encyclopedias. I read encyclopedias, like, every night before going to sleep.

—Do you remember what they were?

—They were the normal Encyclopedia Britannica. I would just pick a volume and go through it. I slept in a bunk bed, and encyclopedias are heavy. When I was done, I would always drop it on the floor, and it would slap on the ground, and I’d always hear my brother who slept below me. But yeah, I read the encyclopedias a lot.

—I did not come to them myself. It wasn’t because I was seeing them. They were given to me by adults, and because an adult gave it to me, I felt I had to get into it. I’m glad I did. I’m sure–speaking of the subconscious, while my synapsis were being formed, they wired themselves in there, and hopefully did some good.

—My nephew is in the seventh grade, and I did mail him Catcher in the Rye with a note describing the things I just described to you, and got absolutely no response from him at all.

—You never spoke to him again? He ghosted you?

—He totally ghosted me. I thought it was a special thing because it was a special thing for me. Uninterested.

In late August, I made the following attempt at crafting an introduction for this essay. It reads like the introduction of a VICE article. I feel ashamed of it and am therefore including it here:

I’m talking to Jamie Stewart while sitting on the floor of a brick Federal Townhouse owned by a pair of married architects in Hudson, NY. Where I am sitting is also where I sit for thrice-weekly psychoanalysis sessions that take place via Zoom, the corporate networking tool Stewart and I are also using to talk, albeit without our faces. “Like prehistoric people,” he says.

The carpet is white and the wooden coffee table where my laptop is stationed is low to the ground. There is one piano, two pale blue chairs, four staghorn ferns. And I too am duplicated. Something I do not yet know is that my substitute psychotherapist for the month (my psychoanalyst is on vacation) went on tour with Stewart.

Prior to our conversation, I misconstrue its scheduled time, having confused Pacific Coast and Eastern Standard Time in an email. Therefore, when I arrive early and our conversation is not for another hour, I bide time by 1) brainstorming questions I don’t actually ask; and 2) by practicing 25 minutes of Zazen while facing the Victorian home’s backyard, which contains ten trees planted by the architects.

Stewart arrives at our interview wearing a textual avatar whose letterforms I won’t relay here, suffice to say I have a tattoo on my chest of the wingéd creature to which said avatar alludes. His voice sounds like his voice sounds in the podcasts to which I listened while conducting research for this essay, for I cannot attempt—which is to say, I cannot essay—without a deep-dive. But I also can’t help but feel finicky, meticulous, tightly wound. The word interview comes from the French entrevue, from s'entrevoir ‘see each other’, from voir ‘to see’, on the pattern of vue ‘a view’. How can I see anything if I’m exerting control, trying to do a perfect job? Will my ego ever get out of the way? How can I listen to see?

I ask Jamie Stewart if he’s ever been to a monastery

I ask Jamie Stewart what books he read as a child

I ask Jamie Stewart how he’s feeling

I ask Jamie Stewart how his class went

I ask Jamie Stewart about his meditation practices

I was not planning to ask this question, I say

Did your nephew ghost you?

I feel self-conscious

Jamie says one exercise a therapist taught him is to breathe in on re and breathe out on lax

It works, he says, and I try it

I ask Jamie Stewart about his writing routine, and he explains he writes for 90 minutes a day after doing vocal warm-ups

I ask Jamie Stewart if he’s read any minimalist or concrete poetry from the late 1960s and 1970s

Late 70s minimalist artwork is my jam, he says

One month later, I visit a show he collaborated on in New York City. Poetry is projected onto the walls

Lighthearted, intelligent, encouraging, open-hearted, curious, shy

Descriptors I write down re: JS

Jamie Stewart is writing a book about sexual foolishness, and is thinking about his patterns of behavior. He says the book he is writing is not fixing him, but it’s carving out a space to feel “rather free of himself.” I ask what this means.

“In no way has it led to any growth or change,” he says. “I think when Ian mentioned to me about wanting to add some elements of reflection [to the book], I mentioned to him that in none of these things do I feel like I became a better person. What I meant by being free from them is that a lot of them have to do with me having treated people quite badly, or having been treated quite badly, and some of it is about very unsafe situations and childhood abuse. And all of that—and forgive this word—all of that energy had been very present in my subconscious thought, and sometimes very present in my conscious thought. I was surprised that by having written them all out... It’s sort of a square way to put it, but they just bothered me less. I think having given them some sort of concrete form, I in a way set them outside of my internal emotional pressure chamber. That doesn’t usually happen with me when I work on songs.”

When Jamie describes his art and life practices, he frequently invokes terminology that feels tethered to Catholicism. A few times, he alludes to not being fixed or better. A few times, he used the word guilt. He describes feeling free from oneself, and also a lack of freedom. In my mind, the idea that one can be fixed implies a hierarchy into which we are indoctrinated as practitioners of faith: god will fix us, because god will bind us. Actual growth, perhaps, comes from recognizing that one cannot be fixed, and that one’s mind is one’s mind, the mind with which one has to live. Those who are worth keeping learn to live with it too. This recognition and this living-with perhaps make the mind a little more translucent: see-through. Can we behold the mind both as an amethyst and as shrink (ha) wrap? Can we wrap the amethyst in shrink wrap and, like Laura Palmer, call it dead?

About his book-in-progress, Stewart says: “It’s much more fleshed out and a more present and linear process than working on songs. So it’s been essentially a relief. It’s not like I feel that in having written it I am free for any guilt I should feel for having done some shitty things, or free from any long-term hurts that I will probably have for the rest of my life, but I think I feel free from the constant presence of those feelings, even if they were at a low boil in the back of my mind.”

/

In the days following August 16, 2021, I take amphetamine salts that have been prescribed to me as an experiment in attention. The implosive past few months have made it very hard to concentrate. I am new to amphetamine salts and don’t realize I can split the pills in half, so I ingest entire doses and research and write with a newfound sense of lyrical focus. I possess no appetite. After hours of concentration, I go running at the gym—more work—and sit alone in a gendered steam room. I feel safe in the steam room, where I keep my naked body wrapped in a towel in order to feel held by something. I can feel my heart beat, and it feels too hot to think. One day, after taking a long shower, I read on the Internet that I should not sit in a steam room after ingesting amphetamine salts. So too does it seem I should not experiment with amphetamine salts in the wake of an event that has left my body feeling disconnected from and frightened of itself. Fairly quickly, I decide I shouldn’t take amphetamine salts at all. But when I return to Brooklyn, I keep them displayed in my bathroom for weeks as a reminder of survival.

—I’m going to ask a sort of open-ended question. You said the book’s not working toward a sense of redemption or recovery, necessarily. In an interview, you used an interesting phrase about “feeling free of yourself” as you wrote these pieces. I’m wondering if you could say more about that: the sort of freedom from oneself that comes from writing, or from not clinging to one’s mistakes, and how this freedom is different from recovery. [pause] Does that question make sense?

—In no way has it led to any growth or change. I think when [Ian Bonaparte] mentioned to me about wanting to add some elements of reflection in it, I mentioned to him that in none of these things do I feel like I became a better person. What I meant by being free from them is that a lot of them have to do with me having treated people quite badly, or having been treated quite badly, and some of it is about very unsafe situations and childhood abuse. And all of that—and forgive this word—all of that energy had been very present in my subconscious thought, and sometimes very present in my conscious thought. I was surprised that by having written them all out... It’s sort of a square way to put it, but they just bothered me less. It’s not like I thought about them and I learned anything. I think having given them some sort of concrete form, I in a way set them outside of my internal emotional pressure chamber. That doesn’t usually happen with me when I work on songs. It’s much more fleshed out and a more present and linear process than working on songs. So it’s been essentially a relief. It’s not like I feel that in having written it I am free from any guilt I should feel for having done some shitty things, or free from any long-term hurts that I will probably have for the rest of my life, but I think I feel free from the constant presence of those feelings, even if they were at a low boil in the back of my mind. Basically [the book] starts from the time I was about five and ends when I was about 40. Throughout that time, for some reason a lot of really crazy things happened to me in the sexual realm, and I participated in a lot of crazy things, most of them not great, although still funny to me. So I think just having that be inside of me all the time and kind of picking away at decisions I would make or my general feelings—having that be attenuated to a surprisingly large degree—that’s where the feeling free of myself statement came from.

I’m writing an essay called “Deep Tissue.”

Define tissue.

Tissue is a group of cells that possess a similar structure and function together as a unit.

My essay grapples with trying to write about a book I’ve never read about sexuality and childhood abuse, and with my own self-destructive sexual patterns, and with a sexual assault that took place as I was trying to write the essay. It weaves together interior monologue, art writing, and an interview with a musician I conducted in August 2021.

It doesn’t sound like it was as bad as it could’ve been.

I’m worried it’s terrible.

![]() , I type.

, I type.

![]()

- “Like other human-borne trauma, intrafamilial abuse damages the human bond. [...] The child must find ways to preserve the integrity of the self in the face of profound vulnerability and narcissistic injury. Emergency measures are needed in defense, but these attempts to cope often become maladaptive.” — Bessel A. Van der Kolk

- “This lack of self-worth and self-esteem is a form of self-harm: torturing yourself with triggering experiences, performing sexually because you feel you have to, placing others’ pleasure above your own. Hypersexualisation is a continuation of one’s trauma, where the physical and emotional pain intertwines and can leave you more distraught than before.” —Harriet Clark

- I read a 129-page dissertation about male childhood victims of sexual abuse by Rick Azzaro. In it, a male subject says: “I [had] a partner for three years, we split up, and even when I was with him, sex was always something that is a big question mark in my head. Even though I have it and I've had quite a bit of it, it doesn't feel like I can go very deep beyond the superficial part when you love somebody and you have sex with them, it's hard for me to do both of those.” As I read, I feel angry because I see a part of myself reflected in this thought.

- Embracing one’s sexuality would be challenging to anyone who previously experienced a sexuality loaded with betrayal, guilt, shame, and overstimulation (Gartner, 2005).

- Azzaro’s dissertation, once more: “Victims benefit when engaged in altruistic and helping activities.”

I think about the past, and about having sex with multiple people who share the same name.

Were all of them in bed with you at once?

hahahahahahha

I was trying to make sense of something.

Was that something a pattern?

“Sex after trauma can be a confusing mess of symptoms,” a website says.

“Don’t kill yourself,” I say to my friend.

“Don’t kill yourself either,” he says.

[laughter]

But the brain can’t live alone.

Trauma, from the late 17c Greek, meaning wound.

Wound, from the Old English windan, ‘go rapidly,’ ‘twine,’ and related to wander and wend.

Twine, from the Old English twīn ‘thread, linen’, from the Germanic base of twi- ‘two’; related to Dutch twijn.

Tissue, from the Old French tissu, or ‘woven,’ from the Latin texere, ‘to weave.’

The word tissue originally denoted a particular material interwoven with gold or silver threads, and later came to denote any woven fabric. Hence, intricacy.

This language—this intricacy—forms a design, a pattern, a twinning.

I explain to a friend how “Deep Tissue” is organized via principles of doubling. Not only is the essay formally bifurcated, but it also serves as a twin diptych counterpoint to “Potted Rubber Trees,” an essay-interview I recently published in GoldFlakePaint. “Deep Tissue” contains two double-yolked eggs; two voices merging; two psychotherapists, two housesits in Hudson, NY; two mysterious scratch marks; two bats; two cats; two multimedia art installations; and two concerts at Knockdown Center in Queens.

“Symmetry,” he says.

I elucidate the spring poetics laboratory I’m teaching at Pratt Institute about twins, doppelgängers, and literary forms of doubling: couplets, diptychs, recto/verso spreads, perfect rhymes, spondees, mirrored stories, autofiction, sequels, and mimesis—not to mention duets, stunt doubles, and other indivisible duos. How can two things look alike and be so split?

In psychoanalytic theory, splitting is a defense mechanism whereby a person compensates for her trauma by dividing the world in half: good and bad, vice and virtue. In survivors of trauma, this split often manifests via the belief a person, place or thing is either safe or unsafe. This dichotomy offers little room for nuance—nothing in this world is fundamentally safe—but the nervous system keeps score.

Along similar lines, survivors of abuse—sexual or otherwise—tend to partition sex and intimacy. This defense is a complicated survival mechanism. In the wake of deeply embedded primordial objectification, how does a person heal the unconscious belief that she is a thing, an item to be used? By disassociating in and from intimate relationships, her body is simply trying to protect itself from further hurt. Even if her mind suggests otherwise.

The effort, perhaps, is not to regress toward primordial trauma, but to regard each circumstance as a bead on a rosary. The challenge, therefore, is not to split, and to keep faith.

The above feels related to the miracle of stained glass, which appears dark from the outside, but when you enter the cathedral, is animated by light.

Cassandra Bristow, my student at Pratt Institute, says the question why? can bring a person closer or further away from the truth.

Recounting everything, I wipe my face.

The paper towel I use is recycled from trees and thereby coarser than tissue.

What is it that passes through me?

Is it a runaway bunny?

A man asks: how can one person use the other for sex if both people are having sex with each other?

To which I do not respond

washed over as I am with

/ shame shame shame shame

When I return to New York City, it is difficult to adjust to my former reality. After all, I have spent half of the past month adjusting to my new life as a table. But I am not a table! I am a horse. I have four legs. My legs may be limbs, or they may be branches of something forked. In Six Memos for the New Millennium, Italo Calvino likens the horse to literary quickness. So even though I am a piece of furniture who is also an animal, I am, in fact, a digression. Lying down on myself, I close my eyes and picture naked bodies. They are lying face down in the center of a room emblazoned with maritime decorations. Which one is mine? The maritime-themed interior design brings to mind nights spent as a teenager walking around the Wal-Mart next to I-80 in Clarion, Pennsylvania. At Wal-Mart, I gazed at the fish in their tanks. Often they were floating belly up at the surface of the water. Were those fish dead? Was I?

Or, conversely, the treatment room was marine-colored, not like the U.S. Armed Forces but rather the beach. There was music playing in it. The music was not by Xiu Xiu. I know this because I had spent weeks studying it. Maybe the treatment room’s music was purchased at a Hallmark store. There was a table whose color I do not remember, and there was a sheet. There was a chair across from the door. I placed my clothes on it. My hair was knotted atop my head. I laid down on the table, pretending I was falling asleep. I thought of The Smiths’ “Asleep” and I thought of Xiu Xiu’s cover of “Asleep,” and I thought of singing along to Louder Than Bombs with my father on a road trip as a child. It was our substitute for conversation. Then “Stretch Out and Wait” came on and my father remarked upon how the song is the most beautiful song ever written. I was 18 years old.

—You talk a lot about the conscious mind, the subconscious mind, and the unconscious in interviews, and I’m wondering—and I hope this isn’t too forward a question—if you’ve been in psychoanalysis. Maybe this question is tethered to hearing you say in another interview that you felt like a child until you were 40. Was there a particular step in your healing process that marked a non-redemptive change or sense of growth? Are you open to talking about that?

—Of course. I’ve been to regular talk therapy and some cognitive behavioral therapy on and off my whole life. Not psychoanalysis, though. I think the mentions of conscious and unconscious mind come from … I think participating in music for a long time, you begin to realize how little of it actually has to do with a decision-making process, and how little of it has to do with oneself actually, and that a lot of it is just being from the universe, and you happen to be the fingers that are plinking out the message. Whatever that may be. And from meditation—I’m interested in different spirituality and also from drug use—and just being curious about how surprising creativity is a lot of the time. Almost invariably when something more interesting than usual is happening, it is just happening. It’s not as if one foot is placed in front of the other and then the other and then it’s [?] constructed. That certainly happens 95% of the time and that can yield some good results. In my experience, any time I’ve done something that’s turned out that a lot of people have attached themselves to, or that a certain number of people have attached themselves to, it’s generally been songs that were just there. And I think almost every musician has talked about how that’s how it seems to work. I suppose that’s my interest in the subconscious mind. And then also, prior to 2017, all of the lyrics the band dealt with had to do with very specific events related to the personal lives of people in the band or politics. And I don’t know why this turn was taken, but writing songs that are very specifically trying to put into words feelings that are related to or oozing out of that subconscious state also became something that could be dealt with. So the narrative and linear factual based ones are still very much a part of things, but kind of allowing--and again, pardon my use of this, “dream state” types of lyrics to come into play--seem like something that the muse was saying was okay to start participating in.

—You said “the muse”?

—Yeah, I don’t know how else to put it.

[laughter]

—I like that.

—And I guess… kind of feeling like a child until I was 40. That just came in a very typical way from being in therapy. There was some very specific abuse that I was dealing with. And other people talk about this experience too, but I had an intense physical reaction to having gone through it while I was in one therapy session. You know, all the typical things: a lot of shaking, a lot of crying, a lot of sobbing, running out of breath, physically vibrating. It was very much as if being exorcised. And it’s not as if the knowledge of those events is erased or anything, but the weight of it seemed to be largely diminished.

—The trauma becomes somatically stored, right?

—It very, very much felt like some physical object had been removed from the inside of my body.

—That’s interesting. I think a lot about the body’s black boxes—you know, these unknowable parts of ourselves that mark us and haunt us, and I think that kind of moment in a therapeutic treatment can be, like, either the black box becoming clear or the black box opening and smoke comes out of it, and you become someone different.

—Some of the smoke… a lot of the smoke floated away.

—I’ve had that kind of moment, a death within the treatment. There’s a really interesting diptych of books by these analysts who work at NYU called Ghosts in the Consulting Room and Demons in the Consulting Room, they’re clinical case studies. They’re really great.

—God, I never thought how that room must have been filled with so much shitty garbage.

—It’s great. We just transfer it to the therapists, right? And then they have to get a massage or something.

—To squish it out.

—Thank you for being open about that. I’m curious about the… These are questions I didn’t know I was going to ask; I hope that’s ok, but…

—This is a million times more interesting than talking about where the band name came from.

I place a hand down my throat and pull out a box lodged somewhere deep within me. The box loosens, but still I can’t come-to. I dislodge it as if it is a tooth. It is trapped near my heart, which is often so purple and sensitive I feel as if it is cuddling my spine. Here, there is something to be said about being attached to walls.

“Do I look like a slut,” I ask my substitute psychotherapist who went on tour with Xiu Xiu.

“Even if you do,” she says, “that should not have happened to you.”

On a particularly difficult afternoon—I have spent a psychoanalysis session shaking, crying, sobbing, physically vibrating, and being unable to find language—I have an appointment to go to the Lower East Side gallery where Xiu Xiu sings along with language and punctuation projected on a wall as part of a collaborative art project with Berlin-based actor and director Susanne Sachsse called I Was a Formalist Pensioner: An Anti-Opera. In a press release, I Was a Formalist Pensioner is described as “an installation with 27 horn loudspeakers, video, 40 miniature slide viewers, photos, objects and paper.” The installation’s language and punctuation is based on the libretto antioper by German painter and graphic artist Kurt W. Streubel. I write to the poet Christian Hawkey in Berlin and ask him if he’s heard of this text. Who translated it into English?

I am still in the process of conducting research for my essay, but the process of exorcising the present (which is also the past) has interfered with my writing timeline. On this particular day, I feel like shit and want to die, but the part of me that keeps going knows walking around in the world will induce at least a subtle alchemy.

The gallery, Participant Inc., is empty when I arrive sans for a person who opens the door. Inside, there is the sound of a very loud jackhammer. The person who opened the door apologizes several times for the very loud jackhammer. I want to tell her that the very loud jackhammer is a diegetic sound emanating from the storyworld of my brain, but instead I stand in front of a wall and wonder if I will ever feel better. I study the text on the wall; a typographer to whom I subsequently email a photograph of the text says the font is Futura. Behind a free-standing wall are outfits covered with televisions, though I cannot recall whether the outfits are concealing plush bodies, or if they are flat on the floor. In fact, I cannot recall if there were outfits on the floor at all, or if the outfits were on human bodies featured in videos playing on the televisions. There is a large speaker in the free-standing wall, or maybe the large speaker is a spiral decoration? I cannot recall. I go into the bathroom, wash my hands, study a stack of books. There is a full-length mirror and possibly one window. The very loud jackhammers are now increasing in sonic intensity. I decide to stick things out and sit down on a form in the center of the room. My back is turned to one wall; my face is turned toward another. I ask the person who unlocked the door how long the installation will exist. On an adjacent wall, fragments of language flicker across an LED strip as Xiu Xiu sings along: it’s nice; not done; the crew is happy; rich in soul; the person is; b o r n; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; why think of something without action; no effort; please negotiate. Is this language a blanket? Two strangers enter the space. They seem to know the person who unlocked the door who keeps apologizing for the very loud jackhammers. What pain lurks just beneath the surface of all of our flesh? I close my eyes and imagine a world in which we all have miniature LED strips running across our foreheads whose flickering words and phrases render visible everything we try to hide. All three people in the space excluding me—i.e., the two strangers and the person who unlocked the door—step outside to talk. Now I am alone in space. At which point the very loud jackhammers cease. I notice a grocery store across the street, recall purchasing guacamole contained in plastic from one of its Brooklyn locations, and begin craving a gluten-free vegan donut from a nearby bakery. Like a fun parent, I will walk myself to this bakery after my gallery visit for a little treat! As language cascades down the wall in front of me, I imagine the Berlin Wall collapsing, and the box in me continues to loosen:

to be to be to be

time period la la la la la

ah

no

ba

ah

a

a

a

in

n

n

n

no

n n

good morning you dry plums

have you slept well?

In August, Stewart and I emailed a bit about minimalist and concrete poetry. The confluence of that correspondence and this installation forms a full circle, as I am now listening to his voice sing punctuation: , , , , : tick tick tick tick. Beyond this synchronicity, that correspondence was a bright point during a difficult month. I remember receiving one email while I was locked in the car parked at a Salvation Army. It felt like a candle—lighght, as Aram Saroyan famously wrote—and I communicated that both in earnest and also as a manic response to my own pain. Now I’m listening to the phrase “chicken run” sung again and again and again, and it is a strange comfort:

As I watch text cascade down and across the walls, contort itself into backwardness, and illuminate and fade away on the adjacent LED strip, I receive a text message from a fellow concrete poetry enthusiast who informs me of his cancer diagnosis. Two months later, he emails me while receiving chemotherapy in a space he describes as a pod. As I envision my friend’s face in my mind, questions arise: What sufferings do we obfuscate? What do we hold inside? Does that really make us feel better? The dissertation I read about childhood abuse victims notes that psychotherapists should never ask Why aren’t you better but rather What happened to you, which feels like such stupidly obvious advice I want to delete the PDF from my hard drive, but instead I reread the paragraph and think about why such advice would ever need to be communicated in this world.

Eventually, another text message arrives. It asks me how I am feeling. In the lighght of day, the litany to which I listen is an apt call and answer:

not better

have tried

have tried

have tried

not better

have tried

have tried

/

Online, I read prose by Stewart about the circumstances surrounding his father’s death, including a detailed account of the day his father committed suicide. This prose appears to be a blog post Stewart published years ago that someone else processing a suicide archived on their personal blog, though I may be mistaken. In the style of Dennis Cooper’s I Wished, Kristin Prevellet’s I, Afterlife, or Blake Butler’s “Molly”—three texts that take suicide as their nucleus—Stewart’s prose about his father’s death is clinically precise and beholds pain as an amethyst. It does not eschew mind’s translucency, nor does it shy from zooming in on a devastating event. Because I have not read the book, I am unsure whether this prose will be included in Anything That Moves.

I send a draft of “Deep Tissue” to Adrian Shirk, a soulmate, collaborator and colleague whose stunning new nonfiction book about utopia, Heaven Is a Place on Earth, is forthcoming. In 2017, Adrian stayed with me for three days in the married architects’ brick Federal Townhouse. Prior to our “leap of faith into new friendship” (to borrow Adrian’s words), we had hung out only once, for the length of a single lunch.

I trust and feel divinely connected to Adrian, who recently moved to the Catskills and started a commune, The Mutual Aid Society. I visited the Mutual Aid Society last summer, sat and played guitar by her pond, harvested kale from raised beds, and spent time drinking tea near and taking 35mm photographs of Adrian's near-dozen pet chickens.

After reading “Deep Tissue,” Adrian wrote: I love this essay. This essay also saved two of my chickens from getting killed by a weasel which I will tell you about sometime, but not now. I don't think there is much to change or rethink. It feels like a living, thinking text. I was struck by the other commenter's idea of recursion but in a much simpler way. I just wonder if there are other repeating images / creatures / objects you might allow to return in that final paragraph / stanza.

The next day, Adrian posted this narrative on the social media application that designs the sights of strangers. The story gave me chills and made me cry. The synchronicity feels, as Adrian put it, staggering:

for two years, these laying chickens have been constant companions, collaborators, storytellers, gleaners, teachers, weirdos, entertainment, makers of abundant eggs. I raised them all from chicks & tended the first flock on my own & later Matthew stepped in as flock-father as we added more, & there were ten: Tiny, Maude, Scruff, Susan, Shy Shy, Amy, Artemis, Razzle, Mary & The Whore + The Holy Woman (full name). It is a sad day on the farm. [CW: Animal death.] Last night, a weasel (or its brethren fisher cat) slithered into the coop & took out seven of them, in a flash. I was standing on my back deck smoking a cigarette in the dark & reading an essay-in-progress by @somanytumbleweeds when I heard odd sounds coming from the coop across the pond. I waited a moment. They weren't shrieks of distress, but there was something eerie & muffled or moaning, & so I ran through the snow in my slippers & unlocked the coop & two survivors rushed to my feet & I said, What is it, what is it, what is it, holding them between my ankles so they wouldn't get loose into the night & there were all the dead hens on the floor in the sawdust. Weasels kill for sport. They do not eat the chicken. They pile the bodies neatly. It is horrifying. I screamed for Matthew or whoever would hear me & Bridget came & we rushed the survivors into the garage & then we returned to the coop. There it was, still snaking around: the weasel, dark brown fur & shiny eyes, shaped like an eel, but mammalian, with shark teeth & slicing claws, completely unafraid of me, pausing to turn & stare blithely into my cell phone flashlight. I was crying, but @bcarsky said, We need to stay & watch to see where it leaves through, we need to see how it got in. So we stood there watching it shimmy slowly up into the rafter & down into the one-inch split in the inner plywood wall it had oozed through. I felt such sorrow for the chickens, for their terror & loss. And I felt both disgust & something like relief that I had seen the weasel, that I wouldn't have to wonder or be haunted by a spectre or a question, that I would get to know what happened, who it was, how it got in, how it will leave, how it will stay out.

Weasels kill for sport. They do not eat the chicken. They pile the bodies neatly. It is horrifying.

/

“After I was raped,” a friend says to me in the midst of my writing this essay, “I started having sex with anything that moved.” She does not know the title of Stewart’s book-in-progress, nor that I am writing about it without having read it.

—Is your schedule written out on a piece of paper?

—Depending on what’s going on, there’s color coding. It’s very silly.

—It’s monastic.

—It’s like a graph.

—If your interior is a monastery, there’s a bulletin board with a schedule you can look at.

—It may be that half of the monastery has been doused with gasoline and is on fire. The internal monastery is a very mixed place to be.

—They say to practice like there’s a fire burning atop your skull. That seems like an apt image. You’re doing it. You’re in the fire.

Tissue, from the Old French tissu, or ‘woven,’ from the Latin texere, ‘to weave.’ If I weave together the variable parts of the past four months, to what do they amalgamate? I am presently writing this while sitting on a bench outside of the Knockdown Center in Queens. The date is November 20, 2021. Because everything happens twice, I am here for the second week in a row. Last weekend, November 13, 2021, I was here with my friend Cam for a hybrid Xiu Xiu/Wolf Eyes/Black Dice concert. Now I am by myself, watching a couple of friends in Florist play their first show in over two years. I took a break from writing this essay to travel here and listen, but now I am writing again. As I rode in the car, I felt safe, locked as I was within its sleek metal. But certainly my perceived safety was a delusion, for I was locked in the car with the car’s driver who was also a stranger, and also the car was a car, which is also a weapon.

—And how is the class [for Atlas Obscura] going? Did that start?

—It started yesterday. It went better than I thought it would. I think I prepared twice as much material as was actually necessary. So I had to email the other half of the text to the people who were there. It’s better than not having enough.

—Is it your first time teaching?

—I taught preschool for a long time. And I’ve done, like, guest lectures. But it’s the first time that I completely organized something on the topic. That’s your main job, right?

—I’ve been teaching for ten years. At the beginning, I remember teaching Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space and writing three pages of notes for a freshman composition class. That book’s inappropriate for freshmen.

[laughter]

On November 13, 2021, I watched Jamie Stewart perform a solo set as Xiu Xiu, or Xiu Xiu perform a solo set, while standing next to a potted tree. Cam stood next to me. He was flying to New York City via Manitoba, Canada when I texted him to say hi, but I did not know that at the time, nor had we spoken in months. We are interwoven. While listening to Paul Simon’s “The Obvious Child,” I had a premonition: In winter 2018, we listened to the song a lot, and in the present my body felt overtaken by what felt like a memory-urge to reach out. We had not seen each other since before the pandemic. Eating animal-shaped noodles in my apartment on November 13, we tried to recollect what we did the last time we saw one another. “Was it when I read to you about the virus in a newspaper? Were we sitting on the couch?” How do we begin where we left off when we can’t remember the ending?

Some images I recall from Xiu Xiu’s concert at Knockdown Center include: a food truck illuminated by Christmas lights that smelled like meat; a cavernous hallway; floor-to-ceiling windows; stretching against a bar; a plastic cup of seltzer; a full-length mirror; an orange balloon; a black guitar; striped socks I did not see (they were obfuscated by fellow audience members, and by the potted tree); a Swedish pop star dancing alone; a workout bench; a barbershop mushroom haircut; a girl with a basket of fruit; la la la la la.

Don’t make fun of my night out.

Or, standing under the red lights at the Florist concert this evening, I looked at the potted trees. They were tall, and red and white lights glowed through their leaves, rendering them alien, aliens. There were a lot of EXIT signs in the room, a fact upon which Emily Sprague remarked, and I watched as 50% of people onstage faced each other. One body was light. One body had a hood pulled over its head. In order to see everything, you must begin with what’s in front of you. As I studied the stage, I noticed the lights beaming down a Xiu Xiu logo, but I am always seeing letterforms in space.

It is November 24, 2021, the day before Thanksgiving. I am doing better, which is not forever, but the leaves have changed, the weather is colder, and I have been going to bed alone. Last night, I dreamt I told two strangers I was traveling by myself, though the where and why of my travels were unspecified. You’re courageous, they said to me.

Last weekend, my former life partner Jeff came over to pick up some objects that had been left behind after he moved out in 2017. We had not seen each other since before the pandemic, but many reunions have been taking place. It always feels strange in a non-linear way to see Jeff; it is always a time slip. I’m sorry you lived with me when you did, and that we saw the messiest parts of each other. The past is no longer, but it’s not as distant as we think. Nor has the future not yet taken place. Like tissue, it is woven between us.

May I take your portrait?

Jeff is sitting at the base of a tree. He is wearing a baseball cap and a Pumpkinhead t-shirt. Smile, I say, and it’s suddenly yesterday. And then like a cinema jumpcut, we are standing in front of his VW Jetta, saying goodbye. Its inspection sticker reads 1111. I believe in grace and mystical forces greater than me but am trying to loosen my delusion that every symbol means something beyond the fact that my unconscious mind is attuned to them. Whose mind doesn’t want to try and organize via magical thinking the ambient and concrete losses that accompany being alive? Jeff’s car’s name is Trakl, the name of a dead Austrian poet about whom the aforementioned Christian Hawkey, based in Berlin, wrote a book.

Jeff drives back to the city where he now lives.

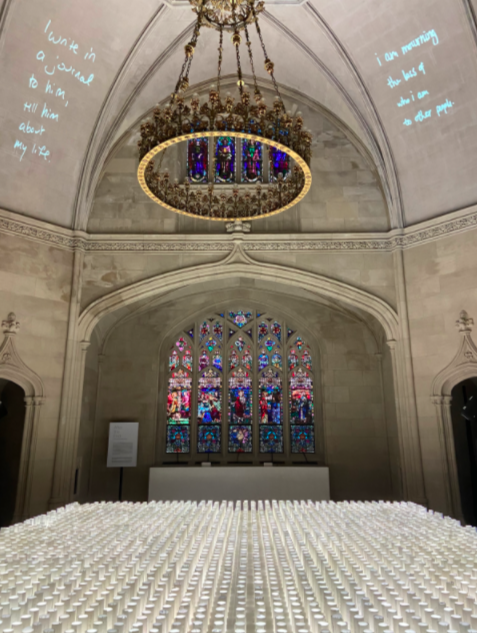

After saying goodbye, I visit Greenwood Cemetery with my friend Savannah. We circle the lake and watch the sky turn pink before entering the Historic Chapel, where a public installation called After the End is showing. Created by artists Candy Chang and James Reeves, After the End is described as “a public ritual to contemplate loss in all forms [...] equally influenced by religious ceremonies and science fiction.”

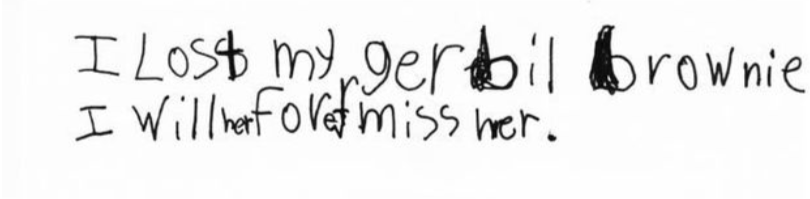

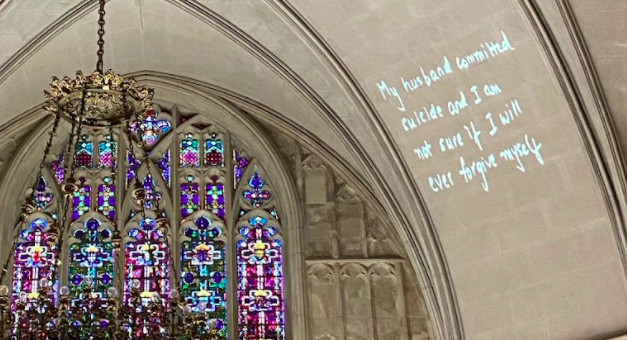

In the Historic Chapel, a sign invites visitors to share their losses on sheets of 8.5x11 paper. These sheets of paper are stacked beneath stained glass windows on opposing sides of the Chapel. Viewers are subsequently invited to bind the scrolls and place them upon an illuminated altar where they resemble devotional candles or glow-in-the-dark cylinders. Visitors can interact with these scrolls, and the contributed losses are also scanned and projected in their original handwriting upon the Chapel’s walls:

The handwriting contains grief of all ages: My husband committed suicide and I am not sure if I will ever forgive myself; loss of FAITH; Things that used to sustain me don’t really anymore; I lost my gerbil Brownie I will her forer miss her; I am mourning the loss of who I am to other people; We love you and hate that COVID-19 took you; people don’t know my disease; WHY DID I LET YOU GO? The projections of these losses remain on the walls for a few seconds at a time and then, like the Berlin Wall or a strong feeling or the details of a day, fade away.

Using a communal marker, I write down my loss on a sheet of paper. I draw a heart next to it and roll the sheet into a scroll. I place the scroll upon the illuminated altar and weep. In silence, Savannah and I sit down on a bench and take in the installation. Sitting on a bench and looking at the projections, alone together with Savannah and everyone who has passed through this room before us, it occurs to me my tears are not my own. The grief is mine and yours, yours and everyone else’s.

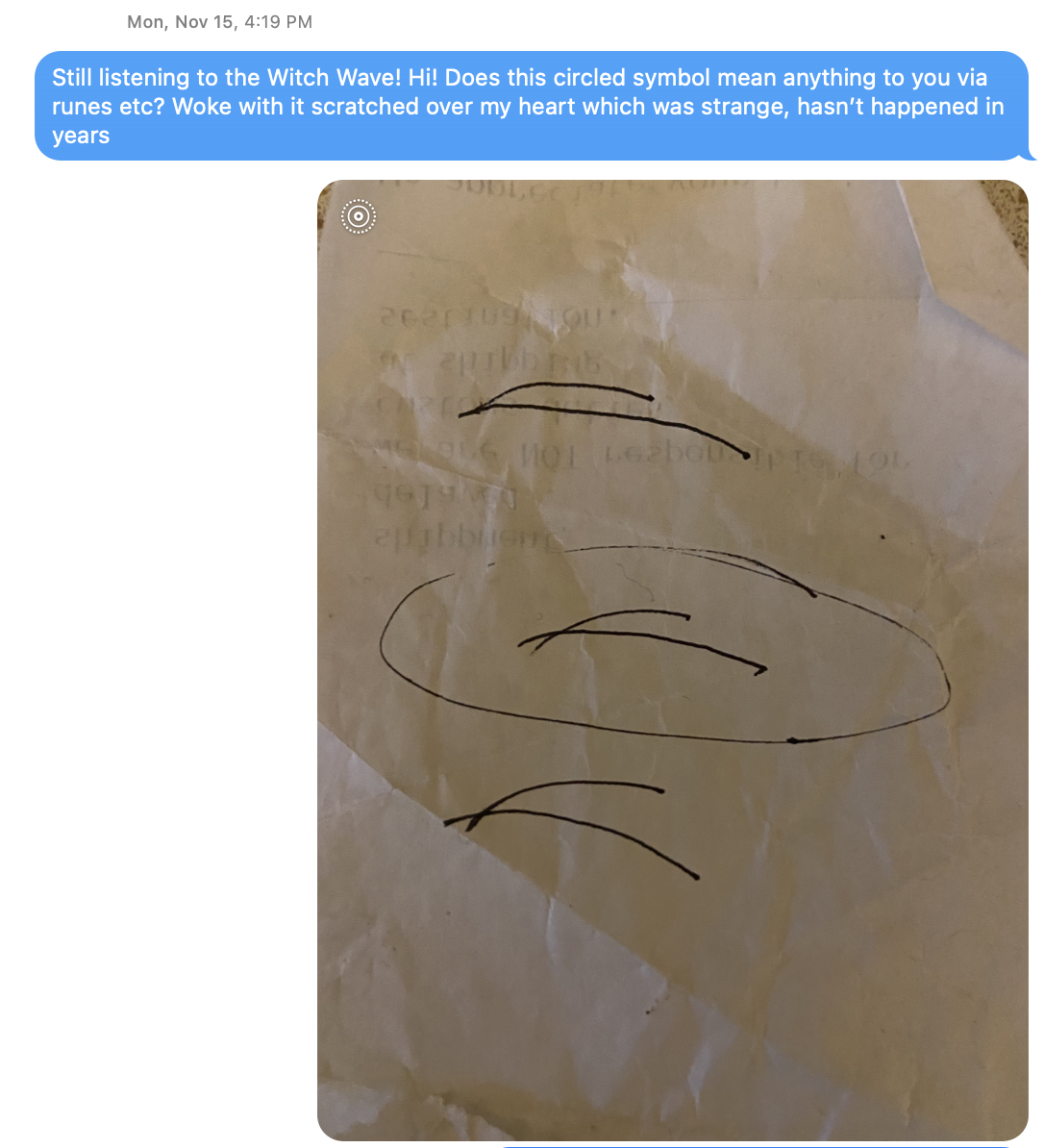

Two nights later, I wake up with a symbol etched over my heart. I had not woken with a mysterious symbol on my flesh since 2017, when the symbol ⨂ appeared on my right oblique, a phenomenon I wrote about in “Potted Rubber Trees,” a twin essay-interview at GoldFlakePaint. Studying the symbol, I write to Jeff:

The next day, I talk on the phone with a cat rescuer about the possibility of adopting a cat. My late cat, to whom I was always nicer than I was to Jeff, has been dead for over a year. The cat rescuer to whom I speak wants to know if I would like to adopt not one cat, but two—a bonded mother and daughter pair. I get cold feet but the image stays with me.

—I don’t know if anybody’s said this to you before, but on Amazon.com, there’s another Jamie Stewart who wrote a book called From Heroin to Marathon Mom. It’s a book about a woman who was a heroin addict who became a committed mother.

—That sounds like the most boring book in the entire world.

—The design is heinous.

[laughter]

—And when I looked up your audiobook which, as you say, is not online anymore, it showed on RateYourMusic.com. The descriptors are really funny, so I thought I’d share them with you. They’re like: sexual comma concept album comma bittersweet comma introspective comma monologue comma male vocals comma disturbing.

—I will shy away from none of those. And I’m glad Jamie Stewart kicked heroin addiction and became a mom.

Before I even began writing “Deep Tissue,” it became an analysis of itself. After all, both my world and writing function in an intensely self-reflexive way, wherein lived experience becomes lodged inside my body until it is loosened via text (or until it literally inscribes itself upon my flesh from the inside-out). As a writer, I am led by intuition and the path of my unconscious. Stewart, who said in this interview that he resists certain forms of analysis, shares my affinity for the unconscious. I trust that what burgeons within us—what I transcribe and offer you as a part of us that both is and is not us—burgeons in service of homeostasis and “the complexities and ambivalences characteristic of that which we experience through the senses,” or what I understand to be Anne Dufourmantelle’s multivalent definition of gentleness.

“I am not an intellectual,” Clarice Lispector wrote in The Hour of the Star. “I write with my body.” Another partition.

Or, as Dufourmantelle writes in Power of Gentleness: “In order to approach and indeed to heal from trauma, we need to be able to go as far as where our body was hurt. We must sew another skin over the burn left by the event. Create a protective covering ad minima without which liberation is impossible lest the trauma haunt the individual’s life.” Nothing can sew up a wound but creation, she posits.

Why did I write this essay? By trying to write the book I have not read, am I suturing tissue within myself, thereby becoming sound? Or am I attempting to essay the book I have not read as a curative treatment? Is this essay a double to Anything That Moves, and if it is, what sort of double is it? A resonance? A synthesis? A convalescence that is shared? And if it is a twin, it must be, as all twins are, different from its counterpart.

Writing these words across a landscape of months helped ease my pain. I don’t want the essay to end, which I hope doesn’t indicate I’m clinging to despair or am fearful of freedom. Because, as Dufourmantelle writes, “[Returning] to the freedom of a non-violated body and to healthy words is already a creation. It rediscovers primitive sensations from the origin of desire, and perhaps also the origin of time.” I am alive and writing these words and am cognizant that, as they move across the page, time slips.

As a gentle organism, “Deep Tissue” hides behind a constellation of writerly defense mechanisms. I disassociate and hide via linguistic fragmentation, rely on ellipsis in order to evade pain, and engage with such intense proto-analysis of my thoughts that the essay could go on forever. And it’s true. I could go on and on with “Deep Tissue.” I do love the idea of an essay or a feeling that continues forever, infinity, a promise, to hell. Yet I’m already different than I was. Nothing I hear sounds the same, and when I look in a mirror, I no longer see myself.

Everything will be taken away.

I open Japanese Death Poems, read a poem about a cuckoo. To it, I listen.

I breathe in on the syllable re- and out on the syllable -lax. To each breath, I listen.

There is breath taken, yet also awe and wonder.

I scatter my body into spatio-temporal shards, if only

to contemplate the word wander in reverse.

On my way back to earth from the woods

[a bird cries]

That’s a sound.

That’s my home.

How do I atone for years?

Am I writing a letter? And if so, to whom?

I consider my cell phone’s wallpaper, then

take a photograph of a weeping willow

and deliver it into the ether.

The author wishes to thank Erica Ammann, Savannah Hampton, Kristin Hayter, Jeff T. Johnson, Anastasios Karnazes, Anna Moschovakis, Will Newman, James Reeves, Cam Scott, Emma Seely-Katz, Adrian Shirk, Nik Slackman, Jamie Stewart, and Felix Walworth. And with oceanic gratitude to my students at Pratt Institute, who inspire me to be more courageous.

Claire Donato is a writer and multidisciplinary artist. She is the author of two books: Burial (Tarpaulin Sky Press), a novella, and The Second Body (Poor Claudia), a collection of poems. She also wrote the introduction to The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer (Fence Books). Recent writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Chicago Review, Forever, GoldFlakePaint, The Brooklyn Rail, DIAGRAM, The Believer, BOMB, and Harp & Altar. Beyond the page, her art practice includes illustration, 35mm photography, video, and songwriting. She teaches psychoanalysis-inflected courses and advises theses in the MFA/BFA Writing Program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she received the 2020 Distinguished Teacher Award.