1.

2.

The word “economic” does not appear in the text of the Department of Homeland Security’s webpage entitled “Obtaining Asylum in the United States”

is not uttered into the court record.

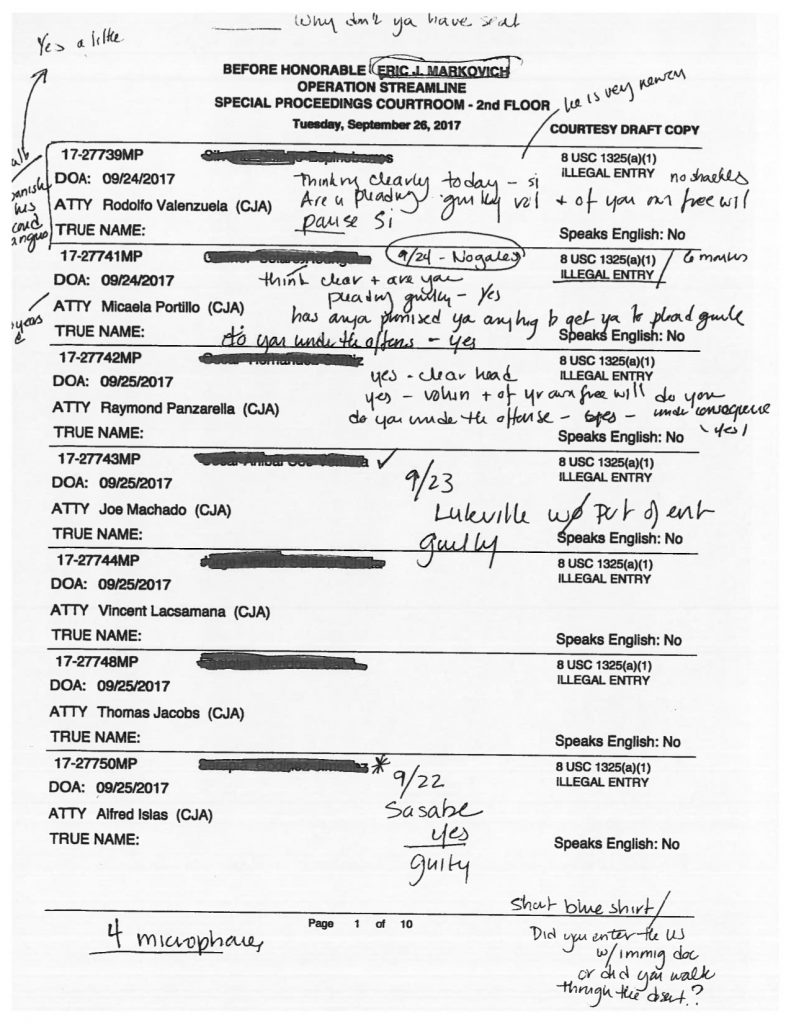

The word “economic” remains in my mouth at the back of the courtroom where I sit scribbling on a legal pad, dangling like a preposition, trying to trace a relation to the seven men who stand before the judge shackled at the wrists, waists, and ankles. [1]

The body is a condition, the nation another.

I used to believe the document tethered the poem to the earth, to soil that one could taste, that could be nutrient to more than one.

But a document can pull a nation out from under you.

In the US District Court, Arizona District, shackles chime like the riggings of a ship in harbor in the moments before beginning a voyage. Seven men approach the bench, one by one they speak directly into the microphone

to be a name in a document, a few words in the record, and one syllable of consent.

3.

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 17, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Nogales without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 18, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Lukeville without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 14, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Sasabe without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 18, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Nogales without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 15, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Sasabe without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 17, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Lukeville without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? On or about March 14, 2017 did you enter the United States from Mexico near Nogales without coming through a designated port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry?

4.

In an endnote to her serial poem “The Book of the Dead” about the murderous exploitation of miners in Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, Muriel Rukeyser wrote: “Poetry can extend the document.”

For Rukeyser poetry became a tool to expand the documentary record, because the profits of Union Carbide, the parent company responsible for the gross negligence that lead to the silicosis poisoning and deaths of anywhere from 764 to 2,000 miners, the majority of whom were African American migrant workers, did not appear in the Congressional testimony about the events,

because centuries of systemic racism did not appear in Congressional testimony or newspaper reports on the “disaster.”

Rukeyser needed to situate primary documentary evidence against eyewitness accounts and interviews as well as within larger systemic forces and legacies in order to make clear that the Gauley Bridge “disaster” was not an exception,

but rather another coordinate in a long trajectory of white supremacy and exploitative capitalism.

I summon Rukeyser now because the words “economic,” “family,” or “asylum” do not appear on the court calendar on the days I attend the Operation Streamline hearings,

because the salary of the private prison corporation lobbyist is absent from the record.

When Rukeyser writes “poetry can extend the document,” she suggests that the poem can account for a document’s limits as well as its elisions and erasures.

The state shapes documents to articulate narratives that benefit the policies of the state, political narratives as fixed and transparent (in places) as the wall that cuts through Nogales, a view to a fractured city or a sky redacted.

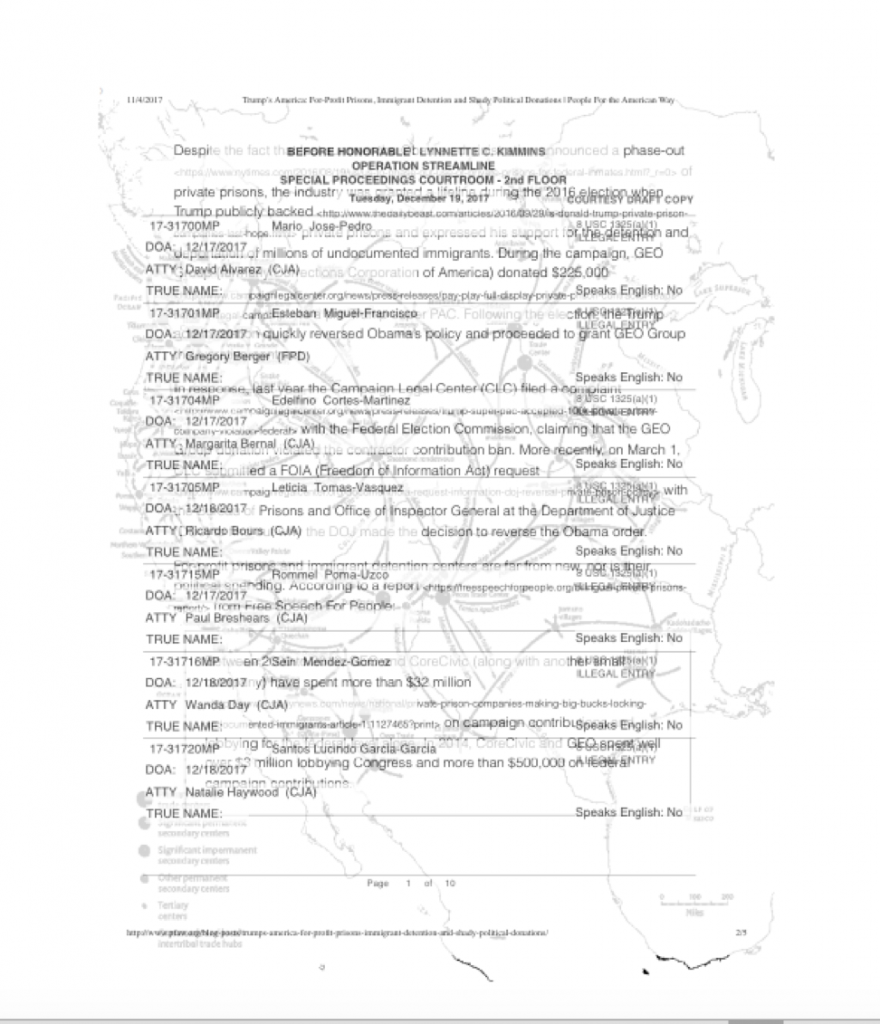

The court calendar for the Operation Streamline proceedings I witnessed includes the defendant’s name, date of arrest, their lawyer’s name, the charges they face, their English language competency. The complete calendar extends 10 pages.

It does not tell us: what spiraled and scurried in the wake of these travelers? What screamed and cried? What debt? What tender? What moans?

Most migrants are permitted to add only three words to the court record: “Yes,” “no,” and “guilty.”

5.

In 2005 Operation Streamline began the prosecution of unauthorized migrants sending them to prison prior to deportation. Each migrant processed through Operation Streamline will leave the proceedings with a criminal record.

In this sense, the process is documentary.

Critics have called the proceedings “assembly line justice,” because as many as 75 migrants might be brought before a judge in a single day, plead guilty to the felony offense of unauthorized entry or re-entry into the United States to serve jail time or face jail time should they be caught again.

Proponents call the process a “deterrent” despite evidence that most of those caught will try to cross again. Many have family in the United States and have lived here for many years prior to deportation. Others flee violence or death threats. Others flee desperate economic conditions.[2]

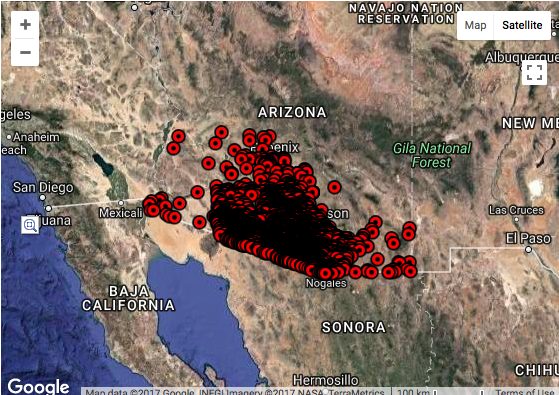

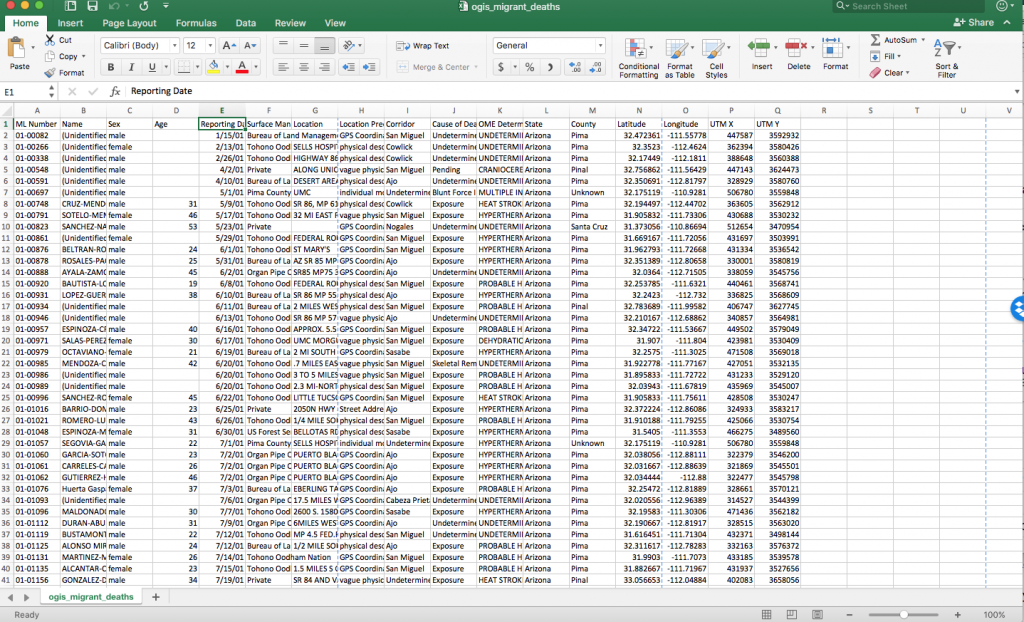

The threat of criminal prosecution and imprisonment often compel those attempting to cross to do so in remote and dangerous terrain, increasing the risk of suffering and death. Since Operation Streamline was first introduced, the border death rate has risen 127 percent from 52 deaths per 100,000 apprehensions to 118 deaths per 100,000 apprehensions in 2010. [3]

However, it is undeniable that the proceedings are successful in their goal of turning the migrant men and women who stand before the judge into criminals.

Despite the consultations with lawyers (whom the migrants meet for the first time briefly before their hearing), despite the headsets and the court interpreter, despite the judge’s (sometimes) detailed statements about rights that they are giving up in order to accept the plea bargain, some migrants cannot follow what is happening.

Do you understand the consequences of pleading guilty? the judge asks.

Yes, I am guilty, the migrant says.

And when the judge asks the migrant why he does not understand the question, the migrant (for whom Spanish is a second language) explains: It’s too fast.

6.

7.

If a line is a dot that went for a walk, then a wall is a line that divides

Nogales, Arizona from Nogales, Sonora.

A deportee is a man who left his kids at a bus stop, was pulled over by the cops, could not produce a social security number and was sent first to jail, then to Nogales, Sonora, to be handed his belongings in a large ziplock bag from the Department of Homeland Security.

The frame determines what we see:

a man walks across the US-Mexico border along a partitioned walkway, a man walks across the US-Mexico border in a caged walkway, US officials escort a man across the US-Mexico border in a human cage.

And if I refer to him as a father of two.

And if I refer to him as a man.

And if I refer to him as a refugee.

And if I refer to him as a migrant.

And if I refer to him as undocumented.

And if I refer to him as a defendant.

And if I refer to him as illegal.

And if I refer to him as a criminal.

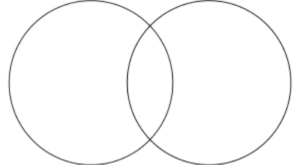

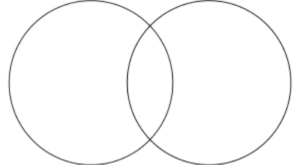

Metaphors make circles of our lives: a Venn diagram of contrast and resemblance.

Who goes where?

8.

In this year of social media algorithms, big-data, fake news, alt-facts and news bots, documentary poetics offers a tradition and a space in which a writer can situate events or experiences within broad histories, without the burdens of mainstream journalism’s anxiety over “balanced coverage,” its obsession for presenting “both sides” to issues that are matters of fact, its imperative to build ratings or market share, its tendency toward representing opinions that favor middle-class white stability. (See NPR.)

Investigative or documentary poetry (or prose) can become a space to record, to unearth, to witness, and to contextualize. But we must not fetishize the document. In isolation it is meaningless, a blank slate upon which any story can be written. (See Wikileaks or Vanessa Place.)

The first step in extending the document might be to discern its limits and to situate it against those other sources that extend its narrative and contextualize its meaning.

Rukeyser knew this.

Sometimes we need to deface the documents to write back through them or into them, to fill in what’s been left out or suppressed, to break a cage of words or reveal a cage of words in order to speak some version of a truth.

In the poem “West Virginia,” Rukeyser transcribes an historic marker at the site of John Brown’s execution (“Site of the Execution of John Brown Leader of the Raid at Harper’s Ferry”) then writes in between its language:

the granite SITE OF THE precursor EXECUTION

sabers, apostles, OF JOHN BROWN LEADER OF THE

War’s brilliant cloudy RAID AT HARPER’S FERRY

With her addition of “sabres, apostles” on the monument, Rukeyser makes Brown (whom she describes elsewhere as “that meteor”) both activist and martyr. She does more than cite the official record, she responds to it.

When writing Zong!, M. NourbeSe Philip focused her attention on one official document, a two-page legal report from the case Gregson v. Gilbert that dispassionately recounted the massacre by drowning of some two-hundred enslaved Africans on board the slave ship Zong in 1781. She explains: “I was convinced that the stories of the events that took place on board the Zong were locked in those two pages; my challenge was to figure out a way to get to those stories.” [4]

But the document did not yield until NourbeSe Philip vowed to trap herself in the body of the text “as if I had locked myself in the hold of the ship,” in order to release everything confined within the legal description. After months of work and research, NourbeSe Philip began to cut into and apart the mere 500 words that constituted the entire legal document; it was then that she was able to channel an experience in order to conjure the full catastrophe.

To access the stories locked in the text or excluded from it we must not only research, we must listen for the voices silenced from the page. We medium. We imagine. We do not appropriate nor ventriloquize. We train ourselves to tune into alternative archives.

On the cover of Zong! just beneath her own name in reference to spirts that spoke through the legal document to her, NourbeSe Philip includes the phrase “As told to the author by Setaey Adamu Boateng.”

9.

The word “economic” does not appear in the text of the Department of Homeland Security’s webpage entitled “Obtaining Asylum in the United States.” The word “family” is absent. The word “asylum” is only spoken into the record twice in reference to a legal privilege the court cannot grant.

A frame structures. An archive divides. Suppressions abound, an old trick of white supremacy (ref: the Gag Rule, a series of rules that prevented any mention of slavery on the floor in the US House of Representatives from 1836-1844, by tabling, without discussion, any petitions that contained the word).

We must not replicate the elisions of the state. We can extend the document or deface it to discern its limits and to situate it against those other sources that broaden its narrative and contextualize its meaning.

There is the court record and then there are the articles of clothing found and four sets of remains recovered in five days in December 2016 from volunteers searching in the area near Ajo, Arizona.[5]

There is the court record and then there are the poems of Javier Zamora, a Salvadoran poet who crossed the desert here near Tucson, who writes in the poem “To the President Elect”:

….We craved water;

our piss turned the brightest yellow—I am not the only nine-year-old

that has slipped my backpack under the rancher’s fences.

To access the stories erased, sometimes we must record the knowledge we receive from our unarchived experiences. Sometimes we must look to non-traditional sources: folk tale, gossip, rumor, dream, the talk that talks like trees underground sharing sugar and water and energy, the talk we talk in poetry.

In her essay, “Poems are not Luxuries,” Audrey Lorde writes: “For there are no new ideas…. only new ways of making them felt…”

To which I add this corollary: There may be no new atrocities, only new imperatives for finding new ways to make them felt.

10.

11.

In the final row of the courtroom with a legal pad and a draft copy of the calendar, I can only glimpse the migrants’ faces when they enter or exit. I lose track of which defendant speaks, can’t hear what their lawyers say.

About Operation Streamline, the poet Brandon Shimoda observes: “It is easy, in a space designed to bleed people of their stories, for the imagination to go dark and stay dark.”[6]

The court reporter’s face is lit by a screen.

The marshal in the back row rubs his eyes, checks his phone.

Whatever I show you is a representation, filtered and partial.

As witnesses, as researchers, as those who possess an “imagination enlarged by compassion,” (to rewrite Shelley) we need to understand our documents as well as ourselves within the web of power and processes that produce them. We cannot use the documents to serve the “logic” of our poems or our world views, but we can use the poem to help ourselves and others situate themselves within the world.

Sometimes it helps to sit inside a building and feverishly recreate what’s beyond its walls, in order discern one’s orientation.

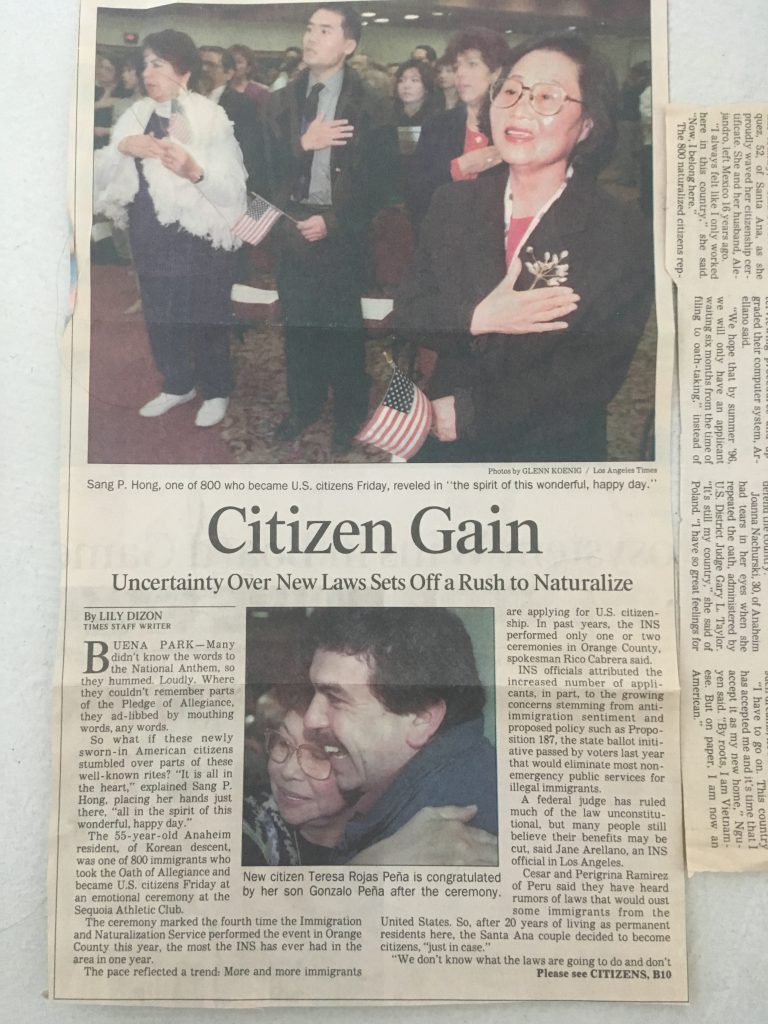

In a safe in our bedroom closet in our bank owned house 72 miles from the US-Mexico border on traditional lands of the Tohono O’Odham Nation, my husband, Farid, keeps his naturalization certificate, a newspaper clipping of his naturalization ceremony, a letter from then President Bill Clinton.

“I want to congratulate you on reaching the impressive milestone of becoming a citizen of our great nation…” President Clinton writes. “You now share in a great experiment: a nation dedicated to the ideal that all of us are created equal, a nation with profound respect for individual rights.”

Not a “milestone,” Farid calls his naturalization a “defensive measure” at a moment when politicians such as Newt Gingrich, former Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, and Pete Wilson, former Governor of California where Farid and his family were living at the time, spread significant anti-immigration rhetoric and promoted anti-immigration policies.

In an experiment, there is no certainty.

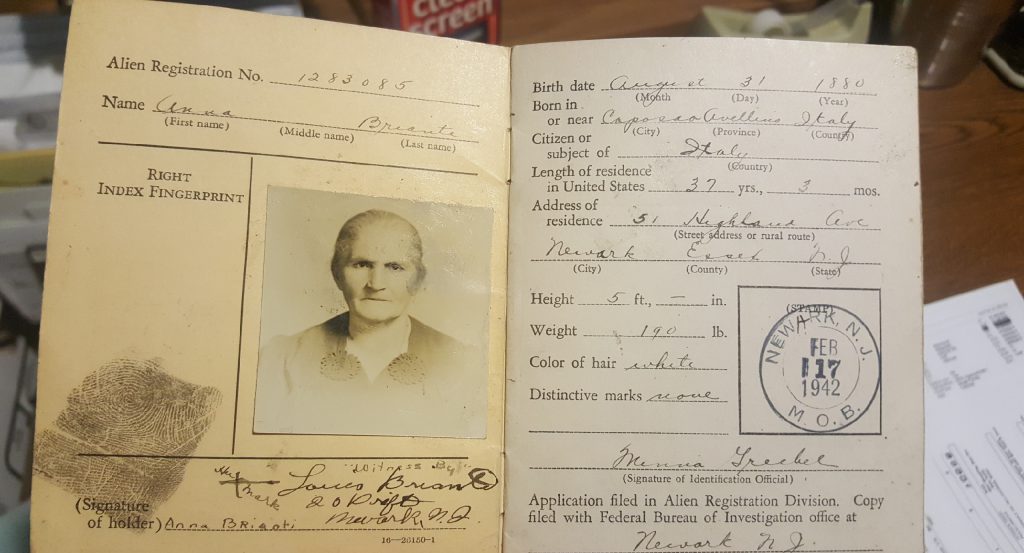

On my laptop, I open a scan of my great-grandmother’s enemy alien identification card issued in 1942 when she had been living in the United States for 37 years. The US government required the card be carried by Italian-born immigrants (classified as “enemy aliens”) during World War II as part of a series of measures that included travel restrictions, the seizure of personal property and internment. My great-grandmother signs her name on the card with an “X” beneath which are written the words “her mark” then “witnessed by” and the name and address of her son. Because of her illiteracy and the war with fascist Italy, she could be deported today under the current president’s immigration policy.

But she was not.

And although I live on occupied lands, nobody asks for my papers.

From my great-grandmother’s illiteracy to my place in the middle class might seem a story of American opportunity, where generations appear like stepping stones toward some goal of a mortgage and a 401k. But the documents do not make evident the structures of white supremacy and limited economic expansion that made “progress” possible, what rights my ancestors’ luck and effort have afforded me.

The metaphors make circles of our lives: a Venn diagram of contrast and resemblance.

Can a metaphor make a human cage?

I do not want my family’s story to be a frame, bent to resemble a human cage.

12.

The words “economic,” “family,” and “asylum” remain unspoken as I sit in the back of the courtroom scribbling on a legal pad, dangling like a preposition, trying to structure a context and trace my relation to the seven men who stand before the judge shackled at the wrists, waists, and ankles.

And you, can you improvise your relation to the phrase “illegal entry,” to the large seal of US District Court, District of Arizona, that hangs above the judge, eagle suspended with talons and arrows pointing?

Perhaps your relation stretches like a wall, bends like footprints towards a road, perhaps your relation spindles and barbs, chollas or ocotillos, twists like a razor wire on top of a fence.

Perhaps you do not improvise, perhaps you shackle, you type, you translate, you prosecute, you daily wage, your mouth goes dry when you speak—paper, palimpsests of silence, palimpsests of complicity and connection never made evident on the page.

Speak into the court record the amount of profit extracted from such men as those before the judge shackled at the wrists, waists, and ankles not limited to the amount of profit that will be extracted from such bodies through the payments that will be made per prisoner per day to the Corrections Corporation of America and GEO Group, but also inclusive of all the profits generated by trade agreements that make labor in the so-called developing countries so cheap.

How can we digest it?

Best of luck to you, the judge says.

Que le vaya bien, the lawyers say as the migrants begin their slow procession out of the courtroom in chains.

And in that moment, from the back of the courtroom, we can decide to accept or forget what we have seen, to bear it or to change it

because we love it, we want it, we don’t care enough to stop it, we hate it,

we can’t imagine how to stop it, we can’t imagine it, we can’t imagine.

13.

[1] In 2017 the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the use of shackles in court violated detainees’ right to the presumption of innocence before their cases are decided. Thus, the shackles are now removed from detainees before entering the courtroom and replaced once they leave.

[2] Both economic conditions and violence in Mexico and Central America can be traced to decades of US policies. See: Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How it Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions among others for an explanation of those links.

[3] Brady McCombs, “Crossing More Dangerous Than Ever for Migrants?” Arizona Daily Star, August 4, 2011. http://azstarnet.com/news/blogs/border-boletin/border-bolet-n-crossing-more-dangerous-than-ever-for-migrants/article_29360a06-be31-11e0-95cf-001cc4c002e0.html.

[4] M NourbeSe Philip from “The Weight of What’s Left Out: Six Contemporary Erasurists on Their Craft,” The Kenyon Review Blog, Nov. 6 2012.

[5] Curt Prendergast, “Four sets of remains found in Ajo area in new effort on crossers” Arizona Daily Star, Dec 30, 2016.

[6] Brandon Shimoda “Operation Streamline” The New Inquiry, May 3, 2017.

Susan Briante is the author of three books of poems, most recently The Market Wonders (Ahsahta Press 2016). She teaches in the MFA program at the University of Arizona. Defacing the Monument ( a meditation on immigration, archives, documentary poetics and the state) will be published by Noemi Press in December 2019.