What makes Helen falter in front of the pawn shop is the beat-up electric propped up in the window, its silver paint peeling just clear of the glass. In her mind she had already touched it. It is so unlike Helen to open the door, to walk up to the counter, to stand doing nothing until she gets found. She angles her interest at a fleet of guitars pegged up high on the wall, a bright blue, a mean red, a flying V, no—those are too shiny, more swagger than sound. The counter guy catches her. “Looking for a good beginner’s model?” he says. He beckons Helen down the wall to the acoustics and lifts a small, shellacked model. “We’re no Guitar Center,” the guy says, “but I know a thing or two.”

Helen stands with the instrument. She hefts it, peers in the hole. She knocks once on the body and hears the hum of the strings’ vibration. She wishes she could explain about the sound she’s chasing: volume and treble, all crackle and spark. “I was thinking—” she says, and tilts her head toward the window display. To try to ask for something before she had the words for it—so cart before the horse, so not Helen.

“For one of those I’d have to sell you an amp too, honey,” the pawn shop guy says. Helen is holding the guitar by its neck. She presses her fingers hard against the nylon strings. It’s not like Helen to chase anything. “Okay,” she says. When she opens her hand she sees the channels the strings have grooved across her finger pads.

Helen carries the guitar back to Nature’s Direction in the soft case the guy threw in. The receptionist goes deliberately wide-eyed. “Do you play?” she asks, in the whisper-voice she uses when someone’s in session.

“Not really,” Helen says. She pushes coats aside in the staff closet to prop the case against the wall.

“I’ll keep an eye on that for you,” the receptionist whispers. Her voice brims with the generosity and affirmation one should expect in a place of healing.

“Thank you,” Helen says, trying to leaven her tone. When she completed her certificate last month her supervisor had suggested that she could work on coming across as more of a soother, as someone with an excess of warmth to give.

After work, Helen walks with her guitar to the west side, where tall trees mute the minimal traffic. She’d found a flyer offering lessons on a bulletin board outside the co-op. Two pull-tabs from the flyer were already missing, which she took as a sign of the teacher’s aptitude. His house has a big wooden door with a knocker she drops twice, three times. “Oh hey,” says the teacher, “Sorry, I was setting us up in the basement.” He’s in socks, a teenager. “I’ve never actually been inside the co-op,” he says, showing her in, “is it cool there? What did we say for the lesson, $20 for 45 minutes?”

“A half hour, I think,” Helen says.

In the carpeted basement the teacher has set up a stool and a folding chair facing each other. “Take your pick,” the teacher says. “Or actually...” He sits on the stool, by a big square amp. Effects pedals crowd the floor like toy cars in a kid’s room. His electric guitar is shiny and yellow, its headstock stamped “Telecaster.” Helen unzips hers from its case. “That’s a good choice for a beginner,” the teacher says. “Do you know anything about music?”

Helen takes herself back to the gray house on Stoller with the open window high on its front-facing wall, to the sidewalk outside it she’d stopped on, listening. “Like what?” she says.

The teacher reaches over and pulls and releases the fattest string on her guitar. “Like if I say that’s an E,” he says. “Does that mean anything to you?”

“Yes,” she says, hazily recalling a circle in the middle of a line.

“Oh good,” the teacher says. He’s already relaxing. He asks if Helen has an idea about what kind of music she wants to play. “You don’t need to be embarrassed,” he says. “I like everything—jazz, whatever.”

What she’d heard through the window, what pinned her in place: volume, distortion, more shards than song. Her face flushes hot. Her teacher is waiting. She says her favorite band is The Beatles, who she doesn’t like or not like.

The teacher says the first lesson will be all about how to hold the guitar. Because his Telecaster is a different shape, he borrows Helen’s acoustic to show her the right way to hold it. He sits and plays a pentatonic scale, wincing at the high notes as if they hurt him. “Not bad,” he says. He gives the guitar back and Helen holds it the way he held it.

“Your left thumb, make it more perpendicular to the neck,” the teacher says. “So you’re kind of bracing it?”

It feels as if someone else’s arms are attached to her body. She pays the teacher $20.

Though it’s late, Helen takes the long way home. She’s never passed the gray house in the evening. She sets her station on the sidewalk. As if someone had been waiting for her, a yellow light flicks on behind the high-set window. An unseen hand reels the window open and delivers a chord like a boat with a hole. The sound sparks every point on her body. At the edge of the lawn she’s a pin on a map, the lawn is a plane and the sound is a loud line across it. The line reveals the distance between the open window and Helen.

*

Because Helen is Helen, she doesn’t let herself walk down Stoller every day. She cuts through the park, strolls her lunch break on Cleary, occasionally takes the bus. She goes for beers with the massage therapists and acupuncturists—they’re celebrating that one of them just bought a house—and drinks a stout slowly, considering the massagers’ body-dips and cadences, how their voices stoke ease. The pub speakers are playing “Hey Jude.” Helen finds herself talking to a Ren with square glasses. “I’m trying to figure out the best sounds to play during sessions,” Helen says. She’s tried beach, rain, chanting. Her clients, unsocked on the table, eager to be unharried, tell her whatever is fine. “Do you know, does the clinic have a music library or something?”

“Music library?” Ren says.

The next day, after her last morning appointment—Helen went with the ocean—she walks past the park to the gray house. She unwraps her sandwich and stations herself. The window is closed and the house is silent and still, betraying no possibility of disturbance. If she were bolder she’d knock on the door. She’d wait on the stoop until someone came home and ask: What do you call the music that eats quiet? She knows that in college there was something called Noise, clumps of kids hunched and tinkering, twisting the knobs, but that wasn’t this. There was no body to it. Helen waits out her lunch hour, one foot on the lawn.

*

The guitar teacher tells Helen that she is now holding the guitar adeptly enough that he can begin to teach her to strum. She should hold the pick loosely, he tells her, but with control. He indicates his laconic pinch. He does some impressions of how she should not move her arm: first—stiffly and from the wrist, next—wildly throwing his shoulder forward so that he pitches from his stool. The proper motion, he says, is from the elbow, “steady like a clock.” The arm, he tells Helen, should always come down, then up, whether or not she plans to hit the strings on both the down and the upsweep. “Be your own metronome,” he says. He suggests that she tap her foot. For minutes and minutes he has her strum, tapping, advising her now to relax, now exert more control. She’s not depressing any strings with her left hand and the sound is murk. She asks: “How do I make it sound... sharper?” The teacher says, “For now, we’re not worrying about sound.” He gives her strumming patterns to practice. “Next week we’ll try a chord,” he says.

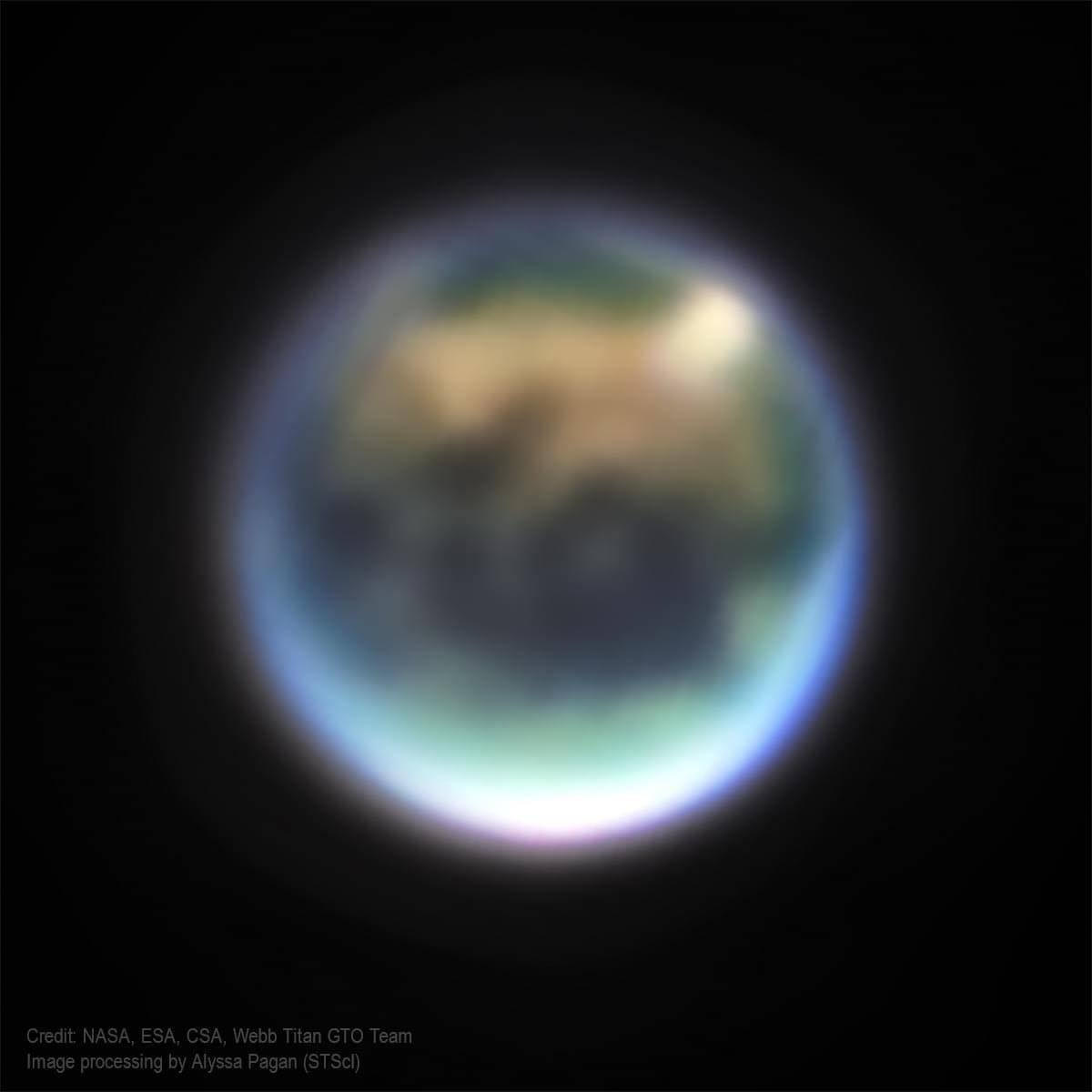

Helen has a late session, and she takes her guitar back to work. She answers “Fine,” ungenerously, when the receptionist asks how her lessons are going. After everyone has left for the evening she strips the sheets and sits on her table and practices a pattern: down-down-up-up-down. She plays the pattern over and over, ignoring the murk, like a pendulum and not. She plays to the posters in the room, the ones left from the previous practitioner—the blue Earth from space, a poem about geese—and her own map of pressure points. She focuses her sight on the point for the shoulder, for vertebrae, as she feels her nerves sizzle and prick.

*

“He’s not home yet,” the teacher’s mom says. The mom wonders how old Helen is but doesn’t ask. Helen, sitting on the hard couch with a glass of water, considers leaving. The mom asks how long she’s been playing. Helen says it’s her third lesson. The mom asks if Helen goes to school with her son.

“I’m 27,” Helen says, which is exactly the age the mom would have guessed.

“Pardon me,” the mom says, “you look so young. What’s your secret?”

“I walk,” Helen says, her typical answer—though she knows the askers seek miracles, products, something they could find in a tincture or tube.

The teacher apologizes for being late. He smells like cigarettes. “Check out what my buddy just taught me,” he says, flicking on his amplifer and settling on his stool, playing a flashy run of notes up and down the guitar’s neck. “We’ll get to something like that in a few weeks, ha ha,” the teacher says. He starts Helen out with an E chord. On a page of Helen’s notebook he draws a grid and dots it. “Chords are shapes,” he says. “That’s basically the most useful thing to remember. I have these names for the shapes in my mind but you should make up your own.” Two of the dots are on one line—one fret—and the third on the fret above them.

Helen tries to see something in the simple design: a legless chair with its backrest reclined. “What’s your name for this shape?” she asks.

The teacher picks at his pickguard, tries to hide behind his hair. “You should make up your own,” he says, “they’re personal?” He shows her how to read the grid and position her fingers on the strings in arcs so they won’t mute the strings behind them. The shape her fingers make on the guitar is not a reclining chair but it is something, she gets it, a feeling, as a bridge describes the river it crosses. The shape suggests intention. She strums and the sound is buzzy and muted, presses harder and it’s better, arcs her fingers more roundly and the buzzing takes tone. The teacher says he is actually impressed. Lift up your pointer and you get an E minor.

*

It’s raining, but Helen refuses Ren’s offer of a ride. She walks to the gray house and stands on the sidewalk until the playing stops, and a hand she can’t see reaches up to reel the window closed.

There’s a path she can take and she knocks on the door. The person who answers is holding a guitar that’s so dark purple it’s almost black. It looks a little like the Telecaster but the model on its headstock is painted over. She’s wearing a black T-shirt. “I heard you playing,” says Helen.

“Was I too loud? I have no way of knowing.”

“No,” Helen says. “How long have you been playing?”

“I’m pretty much self-taught,” she says. “So, forever? A few years? It’s raining,” she says.

The house has gray wall-to-wall carpet and woodpaneling and a kitchen with a cut-out window. It’s almost empty, often vacuumed. It’s the house of someone without a job. “I’m minimal, when it comes to things,” the guitar player says.

“Me too,” says Helen.

West takes classes part-time at the college. “I should be working,” West says. Helen has always worked more than most people she knows. West holds the guitar by the neck as if she might drop it. “Can you play drums?” West asks.

“Me?” Helen says. Something skids inside her. Thank god she hadn’t shown up with her guitar.

“I’m thinking just something kind of spare and messy,” West says. “Like, anti-rhythm but steady, you know?”

Helen feels herself nodding. She knows how to breathe to douse panic. West waits—guitar hovering, sure she’ll end up with the answer she wanted. Yes, Helen has worked for the $60 she has so far spent on guitar lessons, for the $100 she spent at the pawn shop, but her work is satisfying. “Sure, I can try drums,” Helen says. “If that’s what you’re looking for.”

*

Helen calls her teacher to cancel her next lesson. She doesn’t give a reason. At home she takes her guitar out of its case, sits in her one chair and stares at it. Now she sees that she did everything wrong: wrong guitar, no amp, and when her teacher asked what she’d wanted to learn she lied. She might have been able to answer honestly if he had put the question differently, something like “Does sound make you see things?” or “What is your current relationship to loudness?” She closes the case, locks and closets it.

*

West plays guitar in her bedroom—a twin mattress on the floor. A wooden dresser. Helen is surprised by how small the amplifier is. “This little guy’s a monster,” West says. She flicks it on and Helen feels then hears the meaty hum, the sound that precedes the sound. West picks up her guitar. “Is it stuffy in here?” she asks. “Would you mind opening the window?” To reach it, Helen stands on an orange milkcrate. The window’s crank resists her pull until it doesn’t.

*

Between clients, Helen texts West: What music do you listen to? West: The radio. Helen: What station? It takes West an hour to write back: Depends. Helen writes, What should I listen to? No response after her 2 pm session. Nothing after her 3. Helen prides herself on being present for her work, but all she can think about is that she’s blown it, appeared too eager, too unformed. At the end of the day the screen’s still blank. Helen unpins the space poster and the geese from the wall, stuffs them in the trash. It takes West until the next morning to send a link to The 25 Best Riffs of All Time. Then she sends a link to The 30 Best Riffs of All Time. Helen would equally believe that West has studied these and that she has never heard most of them. She would believe that West has never heard of Noise music and that she has a shoebox stacked with tapes in handmade covers and a Walkman that still works, that as she walks or drives or takes the bus to class her ears are never free. She doubts West takes the bus.

*

The next time Helen shows up, West has put out on the floor of her bedroom a metal pot, a box grater, one nicked-up drum stick. West suggests that Helen keep an eye out for those thick wooden sticks from South America. “No tambourines, obviously,” West says. “Did you say you were saving for a drum kit?”

West flicks on her amp. She stomps on her black distortion box. Is her strum metronomic? For the rhythm she’s keeping? For the current of a squall or the foam that feeds it? She starts out standing. She sits on the milk crate. It’s choreography. She stirs up a massy rumbling, bends her knees as if to store momentum for a jump, straightens and stops: “Is the window open?” Helen puts down her drum stick and climbs on the crate. West sets her fingers into a shape Helen recognizes as E. Coated in distortion, the major chord is wheat with sugar, the long lawn, the field. West hits and hits the chord, trashing its optimism, rending its cracks. She faux-falls back onto the mattress, just missing Helen.

Helen, Helen, scratching the drum stick across the grate.

*

Helen’s guitar teacher calls after Helen cancels her second lesson in a row: “Are we cool?” Helen waits to see what case he’ll make. “You were progressing,” he says. “I mean really. It’s slow at first. Some people say start with a song. Should we have done that?”

“Maybe,” Helen says. “Don’t you have other students?”

“I tore those pull-tabs off the flyer myself,” he says. “I heard it was what you were supposed to do, was that shitty of me? We could do a song,” he says, sounding young and desperate. “You like The Beatles, right?”

“My tastes are erratic,” Helen says, trying to keep her voice down against the thin walls. She can hear a brook gurgling in the next room.

“Oh. Okay,” the teacher says.

“Erratic. With an ‘a’,” Helen says.

The teacher doesn’t want to get off the phone. Helen is at work, changing the sheets. “It’s hard when you’re passionate about something,” he says. “The lessons were my mom’s idea.”

“Did she teach you?” Helen asks.

“I wish,” he says. “I mostly learned from YouTube.” He takes Helen’s silence as critique. “Should I have put that on the flyer?” he says. “Would you still have called me if you knew?”

“I don’t mind,” Helen says.

“It’s just hard when you’re passionate about something,” he repeats. “You know? I think you probably know. What’s your job again?”

Helen tells him. “That sounds cool,” he says. “I think I could use some of that. Do you have, like, your own office?”

She books him for a session next Tuesday.

*

West puts together a note, a chord, another, plays through the chain again, again, drops it as soon as it establishes expectation. She mangles riffs. She feeds them from the front end of her intention and unravels them before they achieve their first full cycle. West shreds riffs, kicks at the confetti.

Helen knocks the nicked stick against metal. It’s her job to stay solid, to fortify through repetition, to create the background of ease against which West can flail willfully. She knocks, she works, she walks, she sleeps, she listens. Each day she wakes up the same, feeling different.

*

When they’re hungry, West makes chips and salsa. She makes mac and cheese, and frozen broccoli she shakes into the pot while the noodles are steaming. Helen eats what West offers. There’s a six-pack of Corona in the fridge. Helen is sick and asks for coffee, and West finds some instant and a single-serving drip machine that came with the house. Helen is welcome to bring some coffee to keep there.

After practice, after mac and cheese, West lies down on her back on the carpeted floor of the empty living room and stretches out. Helen lies down. The caffeine thumps in her veins.

“I never wanted to be president,” says West.

“I never wanted to be an astronaut,” says Helen.

“I never wanted kids,” West says.

“I never wanted to buy a house,” says Helen.

West says, “Can you do that thing for my shoulder again?”

West takes off her socks and Helen kneels on the floor in front of her. The point for the shoulder is just below the pinky toe. Helen feels with her thumb until she finds it. She bends her thumb and presses, lets up, presses, lets up. She is opening the channel. Of course West’s shoulder burns, she wears her guitar slung low, and when Helen isn’t there, presumably, curls over her laptop writing papers. Down West’s whole arm, Helen sees sparks. She presses. “You might not feel it right away,” she says.

“I feel it,” says West.

*

Helen’s teacher is impressed with Nature’s Direction. “I can’t believe you’re a doctor,” he says. “If I keep giving lessons, can I put on my flyer that I taught you?”

“I’m not a doctor,” Helen says.

“I knew you would say that,” he says. He rolls his socks into a ball, gets up on the table. Helen hits play on the pink noise she’s settled on. It sounds like nothing—dust held by the sun in an empty room. “So have you quit lessons for good?” her teacher asks. “Think about this: if I like what you do today, maybe we can work out some kind of trade?”

She feels for his liver point. “My friend already plays guitar,” she says. “She needs a drummer.”

“No way,” he says, “you have a band? You really didn’t tell me anything!”

Helen senses her focus mottling. Usually the pink noise coheres her. She lets up on his foot. “I started taking lessons because I was standing far away from something,” she says. “I thought that was the thing I was supposed to get closer to, but what you think you want from far away is different, because you can’t really see what you’re looking at.”

“Who else is in the band?” the teacher asks.

“You don’t know her,” Helen says. “She takes classes at the college.”

“What kind of stuff does she play?”

“I don’t know how to describe it,” Helen says.

“Oh, come on,” the teacher says. “I told you, I like everything. What’s she into, country?”

Because the teacher appears vulnerable with his socks off, because she actually likes him, she decides to try. She almost-whispers, speaks evenly. “You know how there’s a kind of loudness that feels like it’s breaking the air,” she says. “Or—it makes a different kind of air that not everyone can breathe? She has this way of taking sounds and—”.

“Oh, okay. I get it. I think there’s a name for what you’re talking about, it happens a lot in bands,” the teacher says, leaning up on his elbows. “My buddy was just talking about this.”

“I don’t think so,” Helen says, her voice too loud.

“Do you want to be it or fuck it? That’s the name,” he continues, unaware of the walls’ thinness, comfortably barefoot. Helen taps up the volume on the pink noise. “It’s really okay,” he says, sitting up. “I’m not offended. Anyway, I know the names of some good drum teachers.”

Helen doesn’t charge him for the session.

*

West has found another drum stick. Now Helen has no choice. West waits for Helen to count her in, even if she will soon demolish meter. Or forget it? West stops playing. “Aren’t you going to keep hitting the drum?” she says.

“It’s a pot,” says Helen.

“It’s a placeholder,” says West. “Are you still saving?”

Helen is always saving. She could buy a drum kit right now, if it didn’t mean that the money she’d spend on it would no longer be money saved. In her head, she tries something out: would she buy it for West? If what her teacher said were true, is that what she wants: to unveil the hi-hat, then fuck on the floor? The problem is with the word “want.” “There’s something I like about the pot,” Helen says.

West puts the hood of her hoodie back up and stomps the distortion box. Over the electric buzz Helen clicks the sticks against each other four times. West’s guitar creeps and attacks and fake-flourishes, hides in plain sight. Helen knocks the sticks against the pot. Not hard enough.

*

Helen takes herself on a date with Ren from the clinic. The sex makes her feel unHelened in a broad, finite way. She decides she does not want to fuck West or be her. Should she worry, then, about being replaced? Should she diagnose West as in search of a spotlight, Helen becoming baggage before long?

No. Helen, above all, is sensible. West may need a drummer, but she also needs Helen. No. Helen did not arrive on the lawn, at the door, because West needed her, or because Helen needed West. West brought forth a sound. Helen heard her.

*

“I never wanted to be thrown a surprise party,” says Helen.

“I never wanted to learn to cook,” says West.

“I never wanted to be famous,” says Helen.

“I never wanted to be famous, either,” says West. “Is the window open?”

“You must have nice neighbors,” says Helen’s teacher.

“Where do you live,” West says, “in the Hebrew Hills? In WASP Hollow? We live here because we’re free-range,” she says. “We’re free.”

Helen’s teacher is over because there’d been an emergency: West’s guitar had been stolen out of the back of her Corolla. She’d been sure it was gone forever, but the next day Helen had had an idea. Remembering how the pawn shop guy had forced the acoustic upon her, she’d called her guitar teacher and gotten him to pick her up. They’d walked into the shop and seen West’s guitar shining purple-black high up on the wall. Helen’s teacher asked to see it. After, he’d wanted to come with Helen to return it to West, and Helen couldn’t say no. They were indebted.

The teacher plows a chip into the salsa bowl. “You hate the police, is what you’re saying,” he says. “Is that what makes you feel free? Have you guys written a song about that?”

“Helen started a cool one about an astronaut,” West says. “What was the line about the galaxy?”

“Your galaxy doesn’t impress me,” Helen says.

“That’s so good,” West says. “What’s bigger than a galaxy?”

“Nothing,” Helen says. “The universe.”

“Space is the best,” the teacher says. “I was definitely one of those kids.”

“We all were,” says West. “But that doesn’t mean we are now.”

The teacher balloon-animals his face into a caricature of disbelief, looking first at West, then Helen, then back again. “You’re saying that if NASA called today, or Virgin Moon, you wouldn’t drop everything you were holding? Immediately?”

When Helen and her teacher found West’s guitar at the pawn shop, Helen asked her teacher to wait there for a minute while she went around the corner to the ATM and took out $400 from her savings. Her teacher said there must be some way to prove it had been stolen, to not have to pay, but Helen had asked him, politely, to keep his mouth shut. “It’s easier this way,” Helen said.

Now, the guitar Helen rescued is lying on its back on the floor next to where she lies with her socks and shoes off. Helen lets her hand sweep across the strings. Keeping her eyes on the teacher, she says, “National Asshole Space Administration. You couldn’t pay me to go to space.”

Helen feels West get up from her chair. She feels the guitar slide slowly from under her hand, she can sense as if seeing her that West is low-slinging the guitar over her shoulder, walking over to the amp.

“Oh tight,” the teacher says. “That little guy is a monster. What do you use for effects?” West shows him the black stompbox. “That’s it?” the teacher says. “I could bring by my Fuzz Face if you want to give it a try.”

Helen stands up. “She’s minimal,” Helen says.

“Whoa,” says the teacher.

“She’s right,” West says. “Stay, if you want, but we’re fine.”

The teacher shrugs. “No worries,” he says. He shakes out his hair as if he’s settling in. “Alright,” he says. “Let me hear it.”

West flicks on her amp. Helen hears the the sound before the sound.

*

Later, at home, Helen writes a text message to West: What is the loudest song you know? It might take an hour or a day for West to respond. Helen can wait.

On the floor of her room, Helen has lined up a drum stick, a chopstick, a ruler, a hammer. She unzips from its soft case the guitar from the window, a silver Telecaster knock-off, that she went back to the pawn shop and bought for herself, plugs it into the small box of the practice amp she also bought, turns the amp on and the volume up. She sits cross-legged on the floor and lays the guitar across her lap. She starts by barely touching the hammer to the strings, then shakes it until she’s making tiny taps, stirring up a warm hum that fills the room. The room contains it. She makes a hum with her voice that matches the pitch. It’s more of a feeling than a sound.

Sara Jaffe's story collection, Hurricane Envy, is forthcoming from Rescue Press in 2025.

Recommended Reading: