We Responsible Others

Commissioned to develop a sculpture, the artist instead found herself attempting to define the space around it.

What use is a sculpture without a room, a world? she’d asked her gallerist, who reminded her that the municipal client had come with a certain budget. Your job is to make things, the gallerist seemed to misunderstand, when she took as her task something bigger than that.

“Inviting perceptions,” she might’ve said; “convening experiences,” a wall text had once claimed, though she’d cringed at that one. Maybe in the end such phrases revealed that indeed her task wasn’t so grand, that plopping something upon a plinth was in fact the grandest part, grander than any motivating “concept” for her and everyone else to say emptier and emptier things about.

Regardless, she’d like to believe sculpture, at least as she practiced it, had learned it, transcended mere quote-unquote material concerns, but you’ve gotta eat and we have to too, her gallerist insinuated, suggesting that art was an issue of not the hand but the mouth. She wouldn’t go hungry.

Multiples

The street in front of the site conflagrated with cabs, moving vans, electric bicycles, masses. It is said that the first traffic jam on Broadway was precipitated by the excitement over Henri Bergson’s lecture “Spirituality and Liberty” at Columbia University. “The essence of pity is thus a need for self-abasement, an aspiration downward,” Bergson had previously written, hopeful.[i]

Two facts can be false at once.

The child exceeds tutoring. What’s this color called, he’s asked, the instructor or mother pointing to the sky, and in place of blue, cerulean, azure, sapphire, he replies, “everything.”

“All of them, you mean.”

You will obtain a vision of matter that is perhaps fatiguing for your imagination…[ii]

The artist recalled scant philosophy readings from graduate school, slant memories of art theory.

“Verbs surface in the description,” she remembered one art historian, the very obscure one, or, no, the one who wrote obscurely, she was prominent, writing in defense of the public sculpture everyone hated.[iii] “A kind of projectile of the gaze…”[iv] That turn of phrase, as if one could cast their vision away.

That was the artist’s trouble with description, dressing up experience with language: what could it bear on perceiving?

Hiders

Feeling bad about one’s self is not the same as being an artist, a critic had written in a review of her last show, slouched metal sculptures, which—despite being massive, looming and architectonic in scale—read popularly as bodies, frequently her own.

She had worked handily on them, that was true. She wondered to what extent the “she” she possessed had to do with these corporeal misreadings. Though figures they were, bodies they were not. She had sought to foreground the background but all she got back was noise.

Perceiving the edge gave means

out to questioning ends hidden from

what they contained that not absent

and from what snared in the fission

not yet becoming the ends chosen

lived to give up within a limited self

The child mistakes knowledge for affection. The child lives in an apartment leaking water he calls blood. The child locks doors behind him and says nothing inappropriate.[v]

True pity consists not so much in fearing suffering as in desiring it.[vi]

“Look, the city is fine with you placing it outside, so long as you don’t mess too much with the view,” the gallerist haggled over the phone.

The artist stuck on the throwaway “look,” what with there being nothing for her to look at.

Oh, so now I’m responsible for the world, she wanted to argue, but revised her thinking to believe that was already true.

“The whole problem for me—well, not the problem—the whole thing… It’s about the view,” she tried to string together an explanation but found description inadequate.

“Well, we’ll see,” the gallerist non-replied.

The philosopher instructs his wife to burn his papers and she complies.

It is said the child can only eat if his mother feeds him the exact steps. First: Fingers clench; now bend your elbow from seventy-five degrees to twenty-five, so on. It is said the child has never seen his reflection despite being presented a mirror. It is said the child fathered himself. It is said the child was told he was loved and didn’t know what to say.[vii]

Information Has a Way of Escaping

“Function is fused with the unfolding temporal and dramatic events,” the critic argued at a meeting organized at city hall as she tried to explain that the Big Thing for her was that it wasn’t the work that changed but you.

“Well if our vision comprises the world,” he continued, “and call me a solipsist, but I think it does—it does so in time.”

“Okay, I don’t even know what to do with

this issue of being ‘in’ time,

but a reduction to vision fails by the assumption that vision is distinct from other perceptual and bodily modes,” the artist countered the critic and his lonely our.

The critic seemed to say, fine, but text on the page is still something you see.

That’s not my problem, it’s all secondary! the artist wanted to scream, but the press agent and arts commissioner lurked beyond a glass partition. She understood that government funding didn’t prefer women who yell.

“Do you talk even when you fuck?” the artist asked in a low voice she hoped growly, and the critic moved his hand in a way that suggested he’d liked show her.

She wouldn’t like to find out

and so the child turns away from his uncurious mother and instead falls inside, wondering what made one thing real to the mother and not the other, the other things he perceives so vividly, so fully, not yet aching, back aching, head aching, knees throbbing, IT band strained, the bodily insistences that makes imagination less beguiling, makes internal elsewheres impossible

as they’d become

after years in the studio slinging lead.

“Why don’t you just give someone else the instructions,” her gallerist had once urged. “We’ll help you hire them, you’d probably make more money in the end. It would definitely speed up production time.”

She didn’t need the money—her career, her wife’s, the inheritance, it was fine, really. She didn’t need to make things, put on shows, to make a living. Why’d she keep exhibiting? she often wondered when indulging sullen moods.

The critic had also asked her whether she used studio assistants. She said hiring others made her feel uncomfortable, that there was honesty in her hand. He asked if she cooked her own food, did her own laundry, managed her own finances, installed her own work, etc., etc., and her impulse was to retort that it was none of his business but it seemed to her perhaps he was none too different from her handyman or accountant or the intern who had gotten her café au lait, devising a way for her art to be seen and sold, shoveling words to prop it up, or, as the case could be, tear it down, not that people wrote things so mean anymore. Well, except about artists like her, the old guard now, she realized.

Art as an Issue of not the Eyes but the Mouth

According to her ex-husband she’d manifested egomaniacal tendencies, was smug, was no good with the accounts. “All these people running around, wasting their time, supporting you!” was one of the last judgements she remembered passed on her, hurled at her, what, now some fifteen years ago?

Shows, things: The metal she herself hewed.

Rehashing press releases, that was what journalists were up to, was the conclusion from the critics populating the dinners she’d gone to, discussing the laudatory texts overwhelming the art magazines, written for everyone but her, she felt. She guessed she was an easy target for these young writers without care for knowing their history, the gallerists and curators chasing trends and cash and free drinks. As if she didn’t have to put in work to become “the establishment.” Bah!

She’d discovered most critics made their money composing the press releases for the shows they earned next to nothing to write on. It made her dizzy. Her wife handled the finances, thankfully. And the housekeeper, her laundry.

Lingua Franca

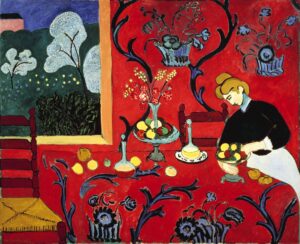

“…god, I’m so sick of all these weirdos in kooky glasses navel gazing, sending these incomprehensible emails with a bunch of words they’ve made up,” the artist overheard one of the city employees saying as she mazed her way through the cubicles to the elevator. “Even this one, like this is the most coherent we’ve gotten so far, but listen to it.” The employee put on a puffed-up pompous voice: “‘The basis of my thinking has not changed, but the very thinking has evolved and my means of expression have followed on.’[viii] Like, seriously? I was just asking if she had a sense of when she could come talk to the contractor.”

“I don’t think they understand what they’re saying half the time either, honestly,” a coworker responded. The artist feigned a cough; the employees remained unconcerned.

The elevator opened, she stepped on, inattentive, taking it up when she meant to go down.

Irreducibility

The pediatric therapist asks the child how long something took and the child cocks his head in a way that to the therapist suggests time wasn’t a measure he could keep external.

Love Poem

Her fist bloomed in the critic’s ass. “This is where we’ll keep your baby,” was her fanged whisper. What inspired the ‘we’? he wanted to know but was too afraid to ask.

She felt sick to her stomach and opened her eyes.

“To be a body is to be tied to a certain world,[ix]

and I’m just over it,” the artist complained to her analyst.

sense (noun) (1) a meaning conveyed or intended; (2) (c) the sensory mechanisms constituting a unit distinct from other functions (such as movement or thought); (6) (a) capacity for effective application of the powers of the mind

“I don’t mean to cause you undue concern,” the pediatric therapist says, “but it seems he lacks the concrete liberty which comprises the general power of putting oneself into a situation.”[x]

It can’t be said that the mother is shocked. “Be that as it may, how can we be certain he’s not better for it?” she inquires.

Whatever the therapist’s answer, it is clear to mother and child both that the therapist hasn’t considered the limits of using silence or words to construe the mind of an other.

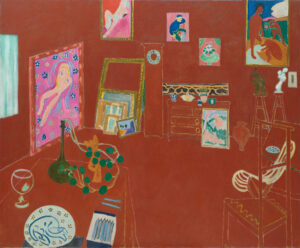

The woolly red carpet[xi]

keeps the child’s attention as the adults debate around him. He brings his eyes into focus where the carpet meets the wall, and then returns to its center, aware of its existence by virtue of finding where it doesn’t exist. He closes his eyes and gray surrounds him, annihilating the distance between him and his perception,[xii] between sensation and sensed, but something about the gray feels impure, though he wouldn’t know to describe it as that; he just knows it doesn’t feel like seeing nothing or being nothing, but it doesn’t not either.

He cups his hands like a telescope about his left eye and zooms in on a small portion of the carpet and what was undifferentiated color blurs with woolly texture, with shadows cast by furnishings, with shadows cast by small threads, with one thread in front of another, one behind that, so on. Against a new backdrop the child can try to conceive this color that his mother has referred to as “red” and which he refers to as “there.”

“To know sense experience, it’s not enough to have seen a red or to have heard an A,” he hears the therapist telling his mother.[xiii]

“I dunno, recalling the qualities of a thing isn’t the same as sensing it?” she upspeaks back.

“Sure, true, but with your son, well, normally it’s the perceived that makes perception but…” The child again closes his eyes and smooshes shut his ears and he can’t feel his skin, almost can’t hear the grownups, can feel the carpet, not as if against him, no, doesn’t feel it, has become it, threads, woven, not yet pulled apart.

Pacifier

“What good is time to a text?” she tried to ask the critic.

“To a check?”

“No, well, also yes. To a text, I said. It’s not that I don’t believe you, trust me, I’m slightly dyslexic, it takes me a while to read, but I’m not convinced that this whole ‘sentential temporality’ thing is a given, but I’ll agree that it takes a moment to turn a page.”

“I think you’re missing the point,” he missed her point.

The critic leaned over, knuckles clammy as they knocked against her wrist, his arm having moved to the side of her chair, and whispered, “philosophy introduces us into spiritual life. And at the same time, it shows us the relation of the life of spirit to the life of the body.”[xiv]

Spirits! “Existential thinking is no excuse for mentalism, dualism! Existence isn’t a two-for-one!”

You can’t just cherry pick from half-forgotten theory to suit your half-formed needs! they both yelled at each other.

“Do you feel my hand?”

“Yes”

“Do you feel focused?”

“No.”

“Do I feel external?”

“…”

“I said, do you feel external?”

“Yes.”

The child asks his mother from where they are coming and she says, “Please, just look ahead.”

“You promised my baby would come out alive,”

the child’s mother wails. “But he’s here, right in front of you,” the therapist insists, pointing at a plastic comb, a pile of muddy clothes, some underwear, eyeglasses.

“But this isn’t the same, those glasses aren’t even his.”

The child opens the office door, squishing his way across the high-pile carpet as if atop a sea of blood and for the first time takes his mother’s hand.[xv]

It is said

that disagreements over matters of perception and perceptions of matter might be reconciled if one quits the business of ornamenting language about them, the press release read for a new hot-shot abstractionist picked up by her gallery. She put down her white wine to take a swig from her aluminum water bottle.

The young painter ambled about the show, hunched slightly to hear the critic trailing his ear. The painter was drinking mineral water, the critic nothing. A white-shirted waiter came to the sculptor and gestured with the tip of a bottle and she nodded and the waiter topped off her pinot grigio. The waiter was off before the sculptor could remember to say thanks.

“What I’m saying,” the critic was saying, “is that I think it’s really original, what you’re doing, this whole business of resuscitating the anti-retinal.”

If it’s original, how’s it a resuscitation? the sculptor thought to herself, and the painter nodded and asked the critic a question much the same.

“Well, I mean, I think—I think, these trends, you know, today with all this neo-figuration, neo-surrealism… Such a commitment to the mind as yours, that’s been forgotten.”

“I hope it’s clear to you that my paintings are in fact things that demand the eye,” the young man said as he made his way past the sculptor and out of his own show.

—

When the sculpture was unveiled at the civic square, a concrete-tiled plaza fringed by short, runty shrubs and color-changing lights, there was a ceremony presided over by the gallerist and the deputy mayor.

Standing in front of the work, Sense II, all the politician could muster was to note that “the job of art is to defy our expectations.” He cut a ribbon that had been suspended between two brassy stanchions. The red polyester fell onto the sculpture, an inlaid strip of metal that read to see.

[i] Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will

[ii] Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

[iii] Rosalind Krauss, “Richard Serra”

[iv] Rosalind Krauss at the hearing over Tilted Arc in New York in 1985. Perhaps the artist is misinterpreting Krauss; perhaps the artist doubts “vision’s intentionality”; perhaps the artist ought to take a walk.

[v] The mother would like to dispute this last point.

[vi] Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will

[vii] The child would say he prefers peas to carrots and apples to raspberries if he were asked; the mother would find his mouth more willing.

[viii] Henri Matisse, 1908

[ix] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology and Perception

[x] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology and Perception

[xi] An example of Merleau-Ponty’s, after Sartre, who was writing on Matisse.

[xii] After Merleau-Ponty

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution

[xv] We all have choices—or don’t.

Recommended reading: The Activist by Renee Gladman, Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson, The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli, Margery Kemp by Robert Glück, Experimental Animals by Thalia Field, Tropisms by Nathalie Sarraute