My relationship to language is an overdetermined, tangled mess: the end result of unequal parts-learning disability, educational deficiency, and self-stylized coping mechanisms. Although I write through it everyday, I'd never considered writing about it until late in the summer of 2007. The novelist Selah Saterstrom sent around an email asking friends to share a brief story with her. She was going through a period of grieving, unable to write, yet overcome by the necessity of engaging with stories, even other people's stories. My writing life thus far had made little room for the purely autobiographical. My mother once asked when l was going to write one of those poems that tells a personal story, like the ones she hears on NPR. My answer was simple: ever. Of course, I was wrong. I sent Selah the following paragraph:

The gutters on the house were dented and old, so clogged with leaves from last autumn that they drained by spilling water over their sides. In later months, they grew huge icicles, a row of teeth surrounding the house. My brother and I would toss snowballs, try to knock them down. Mostly, they shattered as they fell. Sometimes the pieces were salvageable. I took the foot-long tip of one of these and put it in the freezer. I suppose I wanted to commemorate something. Later, I tried to eat it. My lips stuck on its surface. What I didn't know: put your head under the tap and run the water; it'll unstick. Instead, I pulled. The first layer of skin from my lips remained on the icicle. It looked like a kiss. T touched my mouth, moved my hand away. There was blood everywhere.

After this paragraph, I wrote another, and another, until there were dozens and I realized I was actually writing a book. Because so many of these paragraphs were built from the anecdotes and ephemera of my dedication to language and its collision with the errors associated with a peculiar learning disability that I have, I decided to name the book after the disability. Dysgraphia is a work-in-progress, which will be composed of autonomous paragraphs that circle around moments of awe at the discovery of the potential of expressive subjectivity, and then dread at the actual difficulties of inhabiting that expression.

The OED defines dysgraphia as an "inability to write coherently." What sort of coherence is this? What does coherent writing look like? What does coherent writing read like? Barthes, justifying his tendency to employ fragmented brevity, quotes from Andre Gide: "incoherence is preferable to a distorting order." ln Canto CXVI, Pound pulls down his own vanity with the admission, "I cannot make it cohere." Obviously, one can write without coherence; one can orchestrate constituent parts without making explicitly clear the relation of each to the whole. This is nothing new: the palimpsest, the Book of Hours, the collage. As the art critic Meyer Schapiro notes, "Distinctness of parts, clear groupings, definite axes are indispensable features of a well-ordered whole. This canon excludes the intricate, the unstable, the fused, the scattered, the broken, in composition; yet such qualities may belong to a whole in which we can discern regularities if we are disposed to them by another aesthetic." Didn't the Modernist epoch teach us that coherence is a fallacy?

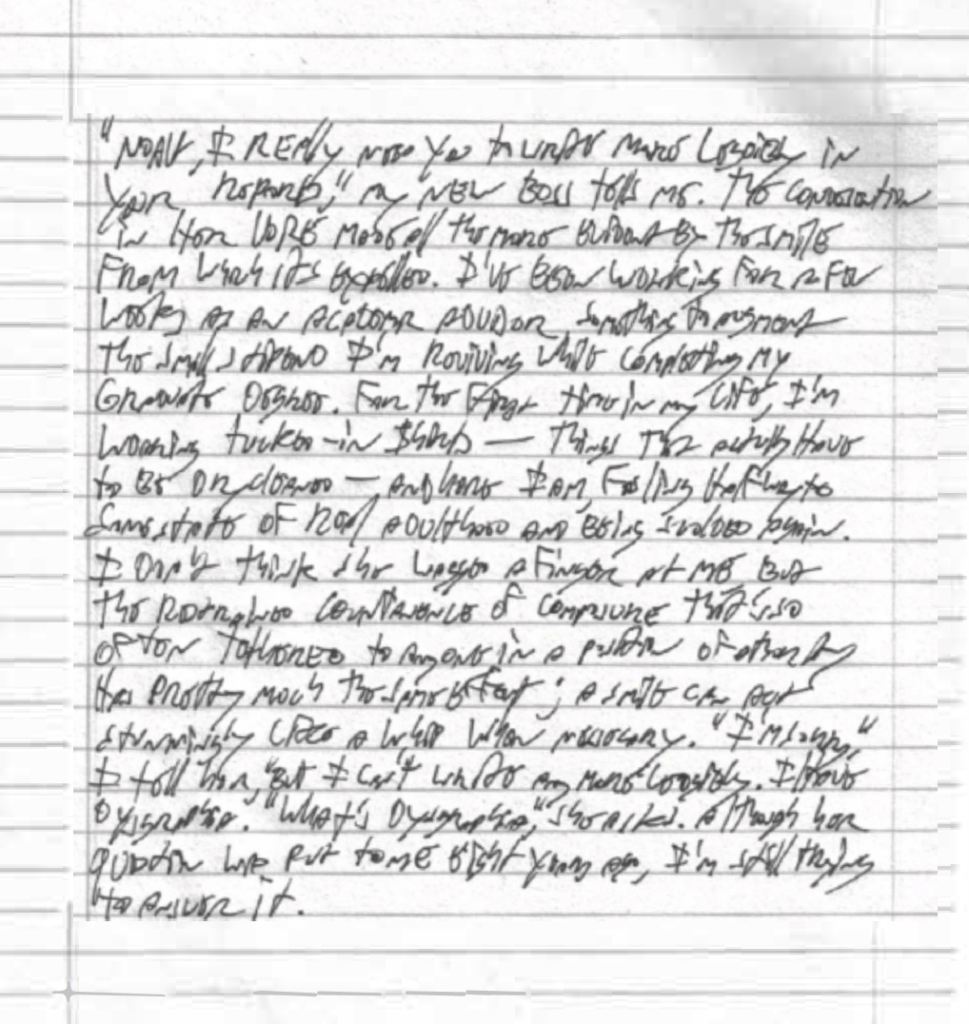

But this is structural coherenc the supposed unity of content and form, part and whole: line, stanza, sentence, paragraph. The relationship of dysgraphia to coherence is rooted in the creation of individual letters and words, in a graphing impairment. Those of us who suffer from dysgraphia are predisposed to problematizing the signifier and the ignificd, to Schapiro's above-mentioned other aesthetic, if only pictorially, in the scattered, broken, and unstable composition of our handwriting. So, the OED definition lacks the requisite specificity. In fact, its entire definition reads: "Inability to write coherently (as a manifestation of brain damage)." While it may be true that brain injury or trauma can lead to the onset of dysgraphia in adults, some of u are born with the condition, whose actual origins are unclear.

My birth was induced with pitocin, a synthetic form of oxytocin, the naturally occurring hormone that causes uterine contractions. Although it is co=only used to aid deliveries, it is also known to potentially reduce oxygen to the baby. My mother tells me that the moment she was given the injection she was gasping, unable to take in a breath, and was given another drug the doctor told her would slow down the effects of the pitocin. The delivery was further complicated by the use of forceps, which left an enduring scar on my cheek. I don't mean to overdramatize my own birth, only to point out its potential link to my learning disability.

The problem with dysgraphia as a term is that it's lexically and etymologically misleading. Dysgraphia doesn't mean an inability to write; rather, it indicates a neurological issue that manifests itself as a deficiency in one's writing. I' m 34 and have published several collections of poetry, as well as dozens of reviews, and essays. There is no inherent incongruity in a prolific writer who suffers from dysgraphia. In navigating grammar, syntax, spelling, and the motor functions associated with forming letters, one simply has to work differently.

For example, as I type this essay into a Word document, dozens of red squiggles appear underneath numerous misspellings. In the paragraph above, I'd written entomologically rather than etymologically. Sometimes, it takes me upwards of ten minutes to come up with a spelling that matches closely enough my original intention so that I might be able to click on the correct choice. When I write even a micro-review, say 300 words long, it can take me a few hours to normalize my prose. Handwriting presents even more difficulty, as mine is often illegible, switching haphazardly between upper and lower case letters-textbook symptoms associated with dysgraphia.

It's not the symptoms that make writing difficult; it's their distortion of the expressive impulse. "Dysgraphia can interfere with a student's ability to express ideas," notes The International Dyslexia Association on one of only a handful of web ites that doesn't recycle the same information on the subject (www.inLerdys.org). "Expressive writing requires a student to synchronize many mental functions at once: origination, memory, attention, motor skill, and various aspects of language ability. Automatic accurate handwriting is the foundation for this juggling act. In the complexity of remembering where to put the pencil and how to form each letter, a dysgraphic student forgets what he or she meant to express." As any writer knows, the lag time between a thought and its written articulation can be an annoyance. For those with dysgraphia, it's often monstrously debilitating.

My diagnosis came only about a decade ago, as an undergraduate on the verge of dropping out because of my inability to complete the foreign language requirement. I stared for hours at Spanish vocabulary words and still was unable to pronounce them. A school counselor suggested I take a battery of tests for various learning disabilities. Nearly ten hours of testing resulted in a 22-page document, which I keep in the top drawer of my writing desk. This report gave me an exemption from the foreign language requirement, but it didn't answer all of my questions about the origins of my difficulties with expression.

Unable to tie my own laces, I wore Velcro shoes until the fourth grade. I stopped

skateboarding in the eighth grade because, unlike my friends, l couldn't figure out how

to ollie--the aerial leap that's foundational to any further tricks. l was never any good

at video games, pool, bowling, anything requiring hand-eye coordination. I learned how to drive a car when I was 25. But what do these deficiencies have to do with writing?

Aren't they simply indicative of some sort of lapse in cognitive motor skills? Yes, they

are--but so is dysgraphia. Dysgraphia itself lacks any solid, clear, universally recognized definition, and instead is discussed in tandem with other learning disabilities and disorders, often as an ancillary component of dyslexia or an additional complication arising from a stroke or other serious trauma. For one attempting to make sense of the condition, this is an irritable uncertainty.

The first moments of my realizatioo that there might be something uousual about my engagement with language were colored with a kind of shame a psychological equivalent to the computer screen's red squiggles. I was in an undergraduate class taught by the poet Martin Espada. We were studying Neruda, and I volunteered to read a poem aloud. Although I can't now recall exactly which poem, I know it was from the collection of Neruda & Vallejo edited by Robert Bly, because my copy of the book is covered in the corrections to Bly's fanciful flights of translation Espada was always quick to point out. Things were going well enough.

Moving across the lines and down the page, suddenly, I was startled. Here and there were words I could define, but couldn't pronounce, couldn't shape into anything sayable, couldn't stop from just sitting there on the page, staring flatly up at me. These days, it's a common enough occurrence in my own classroom, where I often help my students through multisyllabic roadblocks, but this was different. The shame I felt wasn't at my inability to pronounce a word; rather, it was at the instantaneous, public realization that I read in a rather odd way. I don't

sound out words. l memorize symbols, making each word into an individual visual image that I then assign an auditory value while registering its referential significance. Sometimes these auditory values sound preposterously off the mark. I called "dogs" gwoggies as a child, which is cute; as an adult, it's not. A "dandelion" is not a dandy lion, yet, to this day I have trouble remembering so.

Here is a telling passage from the above mentioned assessment document: Mr. Gordon's difficulties with reading phonology [. . .] were evident on a task of reading single-syllable nonsense words. He consistently mispronounced the nonsense words that had a silent "e" at the end. Rather than altering the vowel sound, Mr. Gordon pronounced the word as if the "e" were absent (e.g., "gare" was pronounced as "garr"). On this task, Mr. Gordon obtained a score of 20/36, which is equivalent to a third grade level. This phonological difficulty, most likely, has an impact on Mr. Gordon's experience of decoding, novel word recognition, and reading rate with unfamiliar words.

I've developed a circuitous and eccentric system of phonetic cues for myself. Before

I give a reading, or in preparation for a lecture, I'll meticulously scan a text, fashioning in the margin my phonetic equivalent of any word with the potential to give me pause: ink-co-itly for inchoately; plue-tark for Plutarch; theo-low-gins for theologians. Interestingly, The Teachers & Writers Handbook of Poetic Forms uses a similar method, offering gems like "EL-uh gee" and ''l\SS-uh-nance." My own system embarrasses me. After a recent reading, I accidentally gave away one of my annotated books. I'm not sure who received that particular copy, but it must have been another poet, one I shamefully imagine scrutinizing and mocking my eccentric marginalia. As a participant in a poetics reading group in Denver, I try not to sit too close to anyone, fearful that a stray glance at the notes in my book might reveal this crutch.

On the 1987 television show Star T1·ek: The Next Generation, Geordi La Forge,

played by Levar Burton, was born blind, and outfitted with a prosthetic visor that

to most teenagers looked suspiciously like a banana clip spray-painted silver. This

visor enabled him to see the electromagnetic spectrum. Before his stint as La Forge,

Burton hosted Reading Rainbow, a children's televi ion show on PB , which promoted

reading through book recommendations, reviews, and celebrity appearances.

For nearly a decade, I've carried in my bag a small device that my close friend, the

poet Eric Baus, calls Geordi. Geordi is an electronic spellchecker. Does spelling have

an electromagnetic spectrum? Without Geordi, I feel a kind of blindness.

In first grade I was enrolled in a Montessori school, where students from first through third grade were grouped together, and had three years to work through a sequence of educational rubrics. I put off phonetics. Unfortunately, by the time second grade rolled around, I'd transferred to a public school, where I found myself behind in numerous areas. Perhaps this compounded my future difficulties with language.

A few years later, a sequence of behavioral issues led to my expulsion from the public school system. I wa sent to Beach Brook School, whose website lists the following among its available programs:

- + An intensive treatment unit for the most seriously disturbed children and adolescents

- + Residential and day treatment for elementary through middle school age children with serious emotional and behavioral problems

At Beach Brook, some of my classmates were dealing with much more serious afflictions, including severe obsessive-compulsive disorders and extreme autism. One boy, Tony, would have daymares. He'd be looking out the window, seemingly docile, then suddenly erupt in a bloodcurdling scream. This electrified the room, setting off a chain reaction of nuanced behavioral oddities among the other children, children who never spoke, children who couldn't stop moving, children who, because of Tourette's syndrome, suffered through an endless stream of profanities whenever they spoke.

Education took a backseat to simple containment. Our classroom was a place to practice stillness and submission, not fractions or history lessons. The same was true when I was again institutionalized for nearly three years in high school, this time at a residential facility, as a consequence of numerous behavioral outbursts resulting from my inability to handle the public education system. Were the difficulties attached to my learning disability manifested in my behavioral problems? Were my issues with authority enhanced by dysgraphia?

I can't answer these questions. All I can do is write through them.

Selah's solicitation was a gift. Out of her grief came my J's unshackling. Having come to poetry in the shadow of the anti-expressive, post-confessional, fully problematized I, use of the monolithic pronoun has been for me fraught with anxiety-the ever-present fear of projecting a purely self-aggrandizing stance. Is my I worthy of exploration? Is my I really all that important? Is my I any different than others? These are questions I've embedded within my poetry, but the writing that precedes this essay is something different.

As a disability, dysgraphia rendered my I illegible, untrue; as a writing project, Dysgraphia is an attempt to reveal it, an act of reclamation. Goodbye (for now), je est un autre.