◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In the early 90's, at a massive flea market at the edge of Louisville, Kentucky, a woman from Jamaica looks over the wares. Someone says, Where are you from? She says, Dixie Highway and nothing else, doesn’t look up, just keeps checking out the antiques. She slides into that next unfettered moment in a kind of protective sphere. I'm from right here.

I strike up a conversation with a stranger who wants a sandwich. I go into CVS with him and he picks one and adds a soda. We go up to the register and very loudly he says to everyone nearby, White people don’t do this. White people don’t buy black people sandwiches. Count on it. This would never happen with a white person. I don’t tell him, on the one hand, that my white sister-in-law buys food for people she doesn’t know all the time. On the other hand, I remember that to her, my family and I are acceptable people to marry, we pass.

It’s 2015. I take walks in my neighborhood in Philly. I notice for some reason it seems white people do not say hi back, but all the Black people do. One day, a man with dreads on a bike sees me carrying lima beans back from the grocery store and says, Don’t look down. You have to look up. Don’t look down, the big bad wolf will get you. Chin up girl. And so I do. A few months pass at a time, but whenever I see him he says, That’s better or don’t let them get you down. I feel pretty distinctly this is not something he says to just anyone, and I try to picture how my face and gait must look to him but I can’t quite do it.

My colleague who grew up in a missionary family in Japan gave up her marriage and law practice to travel the world by herself for eight years. She traveled in disguises and went to many countries in solitude. She got to the point she was so used to being alone for days, she would try to talk to ants and get them to do a meeting with her. Better than nothing, better than no one to talk to at all. She remarks that when she was little, she knew in Japan she shouldn’t fight back, but that when they got to America, her father told her that now it was okay, now she could fight back. This didn’t make any sense to her as a little girl.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

With the Principia, Newton became internationally recognized. Among his circle of admirers was the Swiss-born mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, with whom Newton formed an intense relationship that lasted until 1693. The end of this friendship supposedly led Newton to a nervous breakdown.

It’s more comfortable to look at Newton’s earlier life, his many inventions. The fact that in 1668, Newton invented the Newtonian reflector, the first known telescope that used mirror technology. It includes a concave primary mirror and a second flat diagonal mirror. He used this reflector to prove that white light is made up of all the the colors. Any lens will refract light, so he needed mirrors to bypass this splitting. One mirror shows the viewer herself. The secondary mirror placed at an angle allows the light to be bent at 90 degrees, taking the image, literally, around a corner. Allowing precise looking to be done from a distance.

Only once in my life did I see someone I thought looked just like me, a little girl in a museum in London. She was playing by a painting on the other side of the room in a white dress with a ribbon tied around her middle. Her mother came around the corner, may have been mousy-haired, very tall, and British looking. I was so stunned I stared at this little girl for a good long while.

At my new job, I am invited to the going away party of the person who had the job before me. We joke that we should never really be in the same place because we are both half-Asian half-European, interested in the New York School of poetry, film, and the poetry of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: One of us will disappear or it will mess up the space time continuum. At the party his sister or perhaps stepsister walks up and says, Oh my, you look like Cindy! My sister Cindy! I look her up on Facebook. I can objectively see why people think we look alike, but no one looks like me, to me, the way the little girl in the museum looked like me.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Kelly Marie Tran is bullied online to the point that she actually shuts down all her social media accounts. She speaks out about her experiences, her “spiral downward into self-hatred.” Her co-stars defend her, but some have to apologize because they make inconsiderate remarks along the way. John Boyega mentions how for high-profile actors, social media is a place to engage with fans. And that for “those who are not mentally strong, you are weak to believe every single thing you read.” Boyega is called out on this, and he states he was referring to himself and refers to a previous tweet specifically about Tran’s bullying: “Harassing the actors will (change) nothing.”

Tran’s character survives to the final film, Rise of Skywalker. An Asian American writer describes the rationale that Tran’s character’s screen time has been whittled down, the studio says, because she had scenes with the late Carrie Fisher. Apparently, the attempt to cobble together scenes out of older CGI footage was not “photo-real enough,” and sees it as an excuse to trim Tran’s air time. A non-Asian American writer receives the same rationale and says if Disney wants to distance themselves from abusive fans who “can’t tell reality from fiction,” then Disney should “stop giving them what they want.”

For a long time I practiced Vipassana with a meditation teacher who talks about the relief he feels when he opens up his mind to nothingness. This kind of meditation brings me a lot of relief when I have anxiety. I did wait a long time wondering if he was going to say something to address the post I made on his Star Wars page. He says nothing. I say nothing. I wonder if his response would be nothing if he were a person of color or if, to him, that’s a mere category in the face of wu wei or not reacting as a kind of resistance to conflict.

I’m in a sangha listening to a group of newcomers who are largely a Black group of friends, they hear the lojong teaching about resisting conflict. That one does not want to use idiot compassion, which is letting people walk all over you. The group does not return. After my duties as an usher are over, I also do not return. The sangha loses people of color because, as far as I can tell, they are mostly white and don’t know how loudly that fact speaks, in gesture, in actions. As the poet Lillian Dunn writes in her poem, “Chicory is a boundary flower,” “‘you know you’re a vampire/when your invisibility/is the only sign that something’s wrong.”

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

I'm with a group of fellow undergrads talking about cultures and hip hop when a white student we don't see very often pipes up and says, What I want to know is what is white culture? What is it? No one talks about it, so why can’t I find it and have pride in it? I didn't have the words for what I felt. I still don't. A shark passed. Now, 25 years later, I see for the first time that white students refer in their writing, unprompted, to “white people.”

In my late twenties, I go to Greece on a holiday. I haven’t been to Greece yet. I have a strange feeling while I’m there. I look at the gymnasium, the original Olympic field, the buildings and the streets. It doesn’t feel foreign. I have been to China, the island of Guadeloupe, and most of Europe which itself carries an element of deja vu. But Greece seems familiar the way Seattle seems a soundstage replica of someplace you cannot place. I think back on the neoclassical Federal buildings on the quads invented by Jefferson and Greece doesn’t seem officially “foreign” to me.

A student writes a poem fierce and full of coal metaphors that ends, just scapegoats and killers. It’s clearly the best poem he’s ever written for any class of mine he’s been in. Another student suggests that this poem could be more positive and have an uplifting ending. Before I can tell him why this is not the point of the poem, the entire class raises their voice and in a kind of quasi-coordinated unison, they say no and each in their turn explain why the poem should not end positively.

I tell a white student about a story in Citizen by Claudia Rankine. The one about the therapist saying get off my porch. This is a student who does a pretty great job writing ruthlessly about his own privilege. The student gets a look on his face, kind of like a smirk and says, maybe she’s exaggerating. No, not exaggerating. Maybe she is. I don’t say anything but this sticks with me. I’m not angry at the student so much as whatever it is that ruined, for that particular object, his vision.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

When I was in the first grade, the teacher talked about how children and people from other religions don’t get into heaven. I think she picked her words very carefully so that we could understand it was our heaven, our idea of heaven. She probably didn’t want to blow our minds or get into trouble with parents. I remember sitting at my desk thinking that a girl I knew who was Hindu was nice, therefore this only-Christians-in-heaven scenario was bunk.

In Hinduism, the idea of samsara, the cycle of life, struggle, death, and rebirth, is the water that makes the machine of the universe turn, the water in the cogs. At the top of a diagram of the cycle of samsara, there are people in white climbing to the top of a wheel and people in blackness falling down to hell. It puzzles me that there is heaven and hell in Hinduism. I know that these lives lived one after another improve or worsen according to how much merit you have accrued but it turns out there are phrases of time between lives.

I pay, for my own single life, not much of a price for my difference. I know that there are many moments people ascribe goodness to me based on virtually nothing. That I can talk about my mistakes and people wave them off as nothing, or say I’ve sent out a manuscript for 13 years and people say, “Oh but I thought you said that it was quite short a time.” People who have known me for years often correct the narrative they have of me in their minds to something more successful than reality. I sometimes think about how coming back as a tree or bird could be a karmic step up.

This beloved first-grade teacher talked about animals not getting into heaven as well. She was re-iterating Catholic doctrine. Children worked their brains on this one and arrived nowhere. They don’t have souls, she said. We were completely stumped. I got the feeling you get when you see people talking in a car on TV and something is odd about their dialogue because they’re selling the car, not actually conversing. We already knew this was not a working system. The whole concept of authority seemed random to me, hers in particular. When I saw her writing on the board or handing out worksheets, I would think, I can do what she’s doing.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In the mid-aughts, I meet a friend of mine, not Asian, in Chinatown in New York City for dumplings at a very popular and good dumpling restaurant. She tells me not to order what I am going to order but to get the soup dumplings because they are the best thing the restaurant makes. I don’t really want this soup. I get it. I try to drain the pork fat out of the dumpling by stabbing it with a chopstick. She tells me it’s the right way to eat them. The broth inside is good for you. This broth is actually melted fat from a lump of pork.

On Goodreads there is a review of the first book I wrote. In that book are paragraphs like these. There are many reviews of the first book I wrote but the first one talks about how the book simmers with a passive aggressive rage that makes the reader feel ill at ease. Almost sick. This makes me feel funny. When I was young, I was the quiet sensitive person in my family while everyone else had some kind of a temper. The older I get, the more I discover my immense temper. My friend jokes that when she asked someone for a complimentary summary for the back of the book on a book she hadn’t yet completed, the writer called that Buddhist aggressive. On hearing this, immediately I strive to be Buddhist aggressive in all things.

Things that don’t bother me at all: many. Things that bother me incredibly: a few, but they take me down. I discuss with friends how everyone has approximately three things they never want to see in movies. My mother: Nazis, animals being hurt, rape. My friend Peter: alcoholics, Vietnam, abusive priests. Me: animals being hurt, torture, rape. The things that I couldn’t bear to see in scary movies when I was little are different than what I can’t stand now. I was often sent out of the room to not see violence, war violence, or dismemberings.

There is a relief in assuming that Rumi’s poem “Story Water” could be true: “Water, stories, the body/all the things we do, are mediums, that hide and show what’s hidden.” What we see versus what we don’t see and the absolutism of valuing the visible. The poem ends: “Study them/and enjoy this being washed/with a secret we sometimes know/and then not.” This seems a way to negotiate the problem of matter, of being in the world, of dealing not with others but the samsaric worlds created by others. There is only one world. We can’t easily perceive it. Maybe we can’t at all. Maybe I love the name of a camera that doesn’t exist.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

I’m in grade school and watching Trading Places on cable. Dan Aykroyd is a rich young investor, and his mentors make a bet that if a black guy took his place he could/could not be as successful as Dan Aykroyd. They find Eddie Murphy, who has been scamming people by posing as a blind disabled vet in Rittenhouse Square. Years later, I move to Philadelphia and realize that I am exactly in between the rich neighborhood and the not that rich neighborhood. A few years later, a friend reminds me the movie contains blackface.

In Philadelphia, I eat a dosa and some sambar for dinner but maybe too quickly. I walk home and suddenly feel sick. I sit on a stoop to catch my breath and try to recover. I realize I am sitting on the steps of a fancy brownstone not unlike the one Dan Ackroyd’s character walks out of and lives in, in Trading Places. I become simultaneously anxious and indignant, wondering what will happen if someone comes out and sees me doubled over on their stoop. I start to think of things I will say, including an imitation of Eddie Murphy’s character rife with righteous indignation. In Louisville, it wouldn’t occur to me to become anxious or indignant if I happened to sit on a fancy brownstone stoop in Old Louisville. Why not?

It’s a sweltering day in Philadelphia in the 2010’s. A white man walks across the street and addresses a Black man in a maintenance man uniform who is sweeping the sidewalk. The white man is older and has a canvas tote bag and some kind of a hat on. This is in a pretty wealthy neighborhood. The white man says, I cannot believe you people working so hard on a day like today. How do you like that. It must be in the 90’s. The Black man stops and looks and nods but doesn’t engage with this white man. The white man goes on and on and every time he calls this guy my brother a few more times. I can’t see the Black man’s face. I roll my eyes broadly at the white man who doesn’t even register it. I walk on by.

A poet posts on Facebook something he overhears as two women are getting into a cab near Rittenhouse Square. One of them wonders what happens to the people who don’t get into places like University of Pennsylvania and why. The other one says it’s all about the genes, some people just don’t have the right ones. I find myself noticing women in equestrian outfits with ironed long hair and statement necklaces and indiscriminately wanting them to drop dead. I start making for the first time in my life, remarks about white people—to white people.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Back in 2006, a white friend invites me into her bedroom to look at something and while I wait for her to come back from the bathroom, I notice some very feminine shoes. I tell her how pretty they are, and she says thanks, and for some reason I say jokingly, Don’t look like a person who would like shoes like that, do I? She pulls a book off the dresser and says I might like it. It’s called Dictee and it’s by a Korean-American performance artist. Later, I read this book and wonder what else I might be missing.

Later, my all-white dissertation committee recommends that I have a certain professor on my committee which I am confused about until I realize she is the person who teaches Asian-American literature. During a meeting, she remarks that there’s a strong affinity between Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and myself because of her engagement with the French language, displacement, Asianness, Catholicism. I have never, somehow, considered this clearly and consciously while writing about her, though I do sense her work has something to teach me if not directly tell me. The depth of my not seeing this, of my internalized and owned whiteness, of holding myself outside of the nameable, of holding perceived evil away from me, stays with me and changes, eventually, into something facing outward.

I give a reading at a poetry festival at a high school and students in the very back are talking as I’m reading which doesn’t exactly bother me, but I can see from where I’m standing that they’re Asian American or Asian. I pause and take a look at them and keep reading. It’s fine. Someone from the organization later says it’s important for students to hear from someone who might not have enjoyed the same upbringing they have. This takes a minute to register. I have grown up in a very Martha Stewart looking 1940’s subdivision of colonial style homes, columns and all. It’s more like I have been a product of some very white-esteemed cultural capital and grew up so white adjacent that I definitely feel both recognition and familiarity, and oafishness. I’m taller and bigger than most of the Asian Americans I ever meet.

My family is made from two narrowly *not* lost causes. Two people who lived through WWII on two different continents. People who made it because they hid, or flew out, or were sent to the countryside for safekeeping. My existence is built on my father being at the head of a line of people, most of whom did not make it, or who were left behind, or who chose not to make-decisively. Or a man too sick to take a plane ride who gave up his seat. The survivor’s guilt feeling, still, like culpability.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In college, I spend hours reading my English homework in the library. I sit by a giant tree growing up past a window. I sit in the poetry corner of the library. I sit at carrels. One say I’m writing notes, for something so old there might not be a known author, and I see something scratched with an ink pen into the carrel about “I want to fuck Asian babes”: A small caricature of a naked Asian woman in a kind of pretzeled up position, pubic hair and exaggerated eyes. This makes me feel extremely strange, like I want to pick up my books and run to another country. But I just get up and avoid that carrel forever.

I reflect on the one sentence from a professor that lasted me until now and always: We sentimentalize those we oppress. An activist I know supplies the partner quote from Aimé Césaire: "And most of all beware, even in thought, of assuming the sterile attitude of a spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of grief is not a proscenium, a man who wails is not a dancing bear." Where does one stand in relation to one’s fellow people? Where do you stand if your people don’t exist? And what do you call that space?

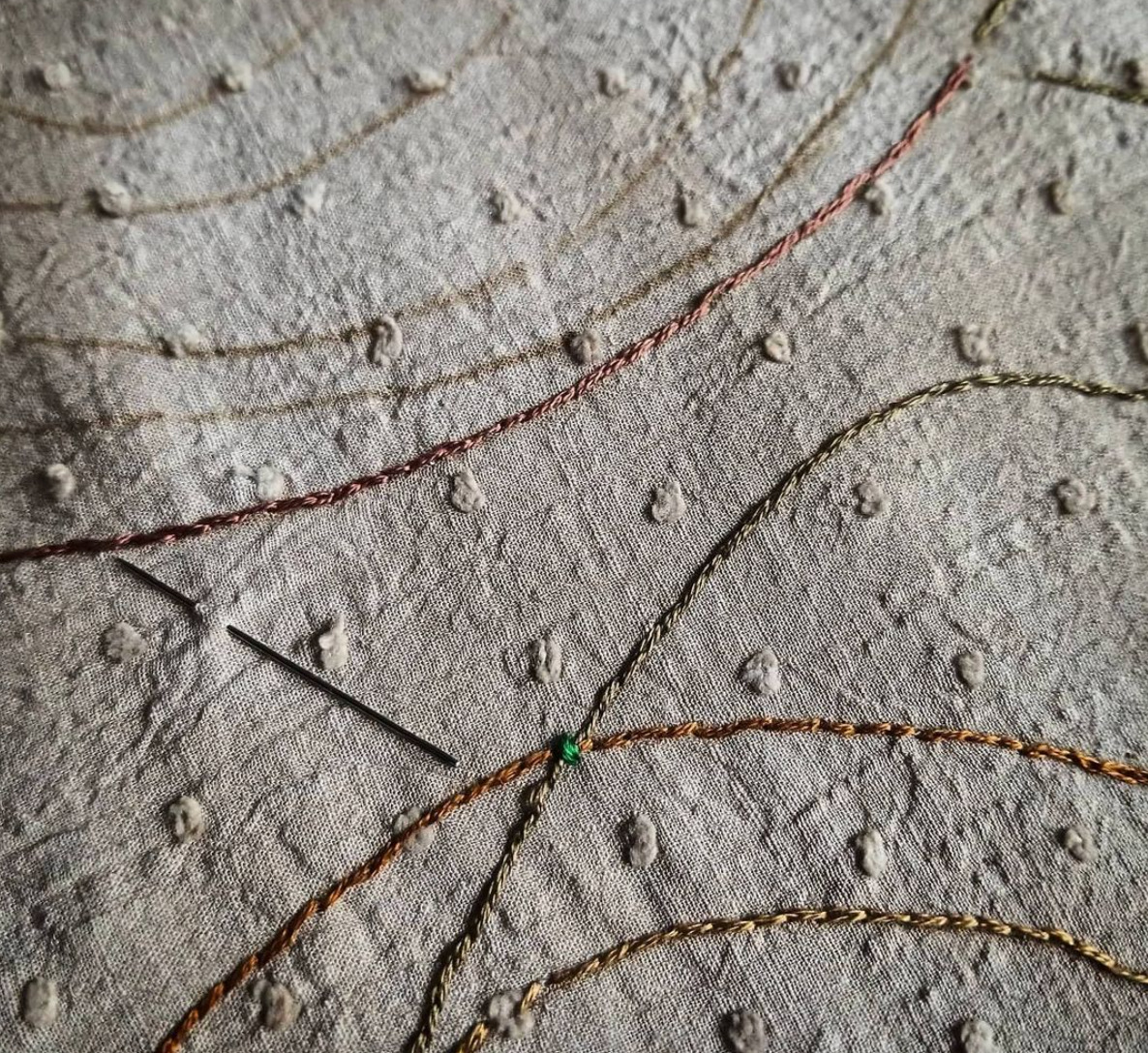

For the quilt of nine stars of Bethlehem, I was using what quilters call a blender fabric, one that would be the unifying background for all the disparate colors on a background. I had found it in person with the stars in the shopping cart so I wouldn’t make a mistake buying fabric online that might be a different shade than its photo. So, I used this fabric and spent so long making the quilt that by the time I realized I needed more, it was no longer in any quilting stores. Anywhere. In the whole country. I put its name in Google and searched for an image of it which I finally did. It was posted for sale on a very old blog site for quilters that looked like it couldn’t be active. But it was, and I bought this remnant, the very last of it.

I spend a few days at my friend’s house in California. It feels more like home than basically anywhere besides the house I grew up in. I stay in the spare bedroom and then go to the kitchen and through the living room at different parts of the day. Sometimes you go through the room like a ghost, she says. Or I hike with a different friend who says, Being with you is easy. It’s like being alone. When I am small, people often turn to me in the back of the car or yell to the stop of the stairs, You’re so quiet. Are you still alive?

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

I spend a summer living in my Asian-American friend’s house while she’s away. Her neighbor, a very old man who has a webcam trained on the parking spot in front of the house, seems aggravated by my comings and goings. My friend comes back and the neighbor makes a remark about “you people.” This almost seems funny to me, like a kid throwing a toy net on me and missing. My friend tries to reason with him but he thinks of many awful things to do and say and eventually she has to call a peace officer.

It is uncommon common knowledge that in 2050 or so the population of the US will be majority brown people. All of California has already returned to being majority non-white. In 2015, John, the man I had gone to China with and dated for five years, talks to me about his children being cute. They each have a different mother but both daughters are half Asian. See how my kids are not completely white? he asks. I see the writing on the wall, he says, this party is over.

My friend sends me a Saturday Night Live skit before the 2016 election. In it, very arch Anglo people dressed in formal business wear, even when they are clearly at home and off the clock, explain that they have had a good run having their men be President of the United States. Slowly their explanation reveals that they have maybe three or four white Presidents left and that since the population of the USA was tipping towards people of color, they should get used to others being President. One of the stiff men in a suit takes an inflated globe and hands it with a commercial smile to a man who seems like he is from Central or South America. This video made all of us laugh, but soon, when we went to try to find it online, it had disappeared.

While at the book fair for the Associated Writers Program book fair, I sat within earshot of another table setting up early in the morning. A woman was chatting with another woman at the table about how to set up the books, when I overheard the brown woman mention that someone’s husband was white and the Anglo woman at the table was very indignant. He’s just a husband, not a white husband. I think about how people signal race in conversations with me all the time. I sit there trying not to stare. I can see people around us at other tables, also trying not to stare.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Cynthia Arrieu-King lives in Philadelphia and is an associate professor of creative writing at Stockton University in New Jersey. Raised in Louisville, Kentucky USA, King has lived in France and has traveled Europe, the United States, Iceland, and China. In early 2021, Noemi Press published the book-length The Betweens. She is the author of numerous additional books of poetry. She posts updates on her blog located here.

Detail of quilt by Judy Hill

https://www.instagram.com/spiritcloth/