A utility amongst the swallows is their music;

they use it to avoid collision.

John Cage, 36 Mesostics re, and not re, Duchamp

In China, it is the year of the rooster.

Here I say it is a centenary for the ‘defamiliar.’

*

I am in a car and am driving away from a town I’ve only visited once before. A passenger to a driver. It’s the first day of another year—early morning—and I am thinking about when I had last been here some eighteen months or two years previously. The day’s coming up like a subject for conversation; its early morning here, and the stars don’t deaden with political diatribe; they’re ascendant and pluralist on a nightly basis. I usually leave the house after dark.

*

Elucidate some of those sentiments for me; blame it on the light.

Elucidate something and censor something else.

Pay me off in an inexpensive gestural play.

*

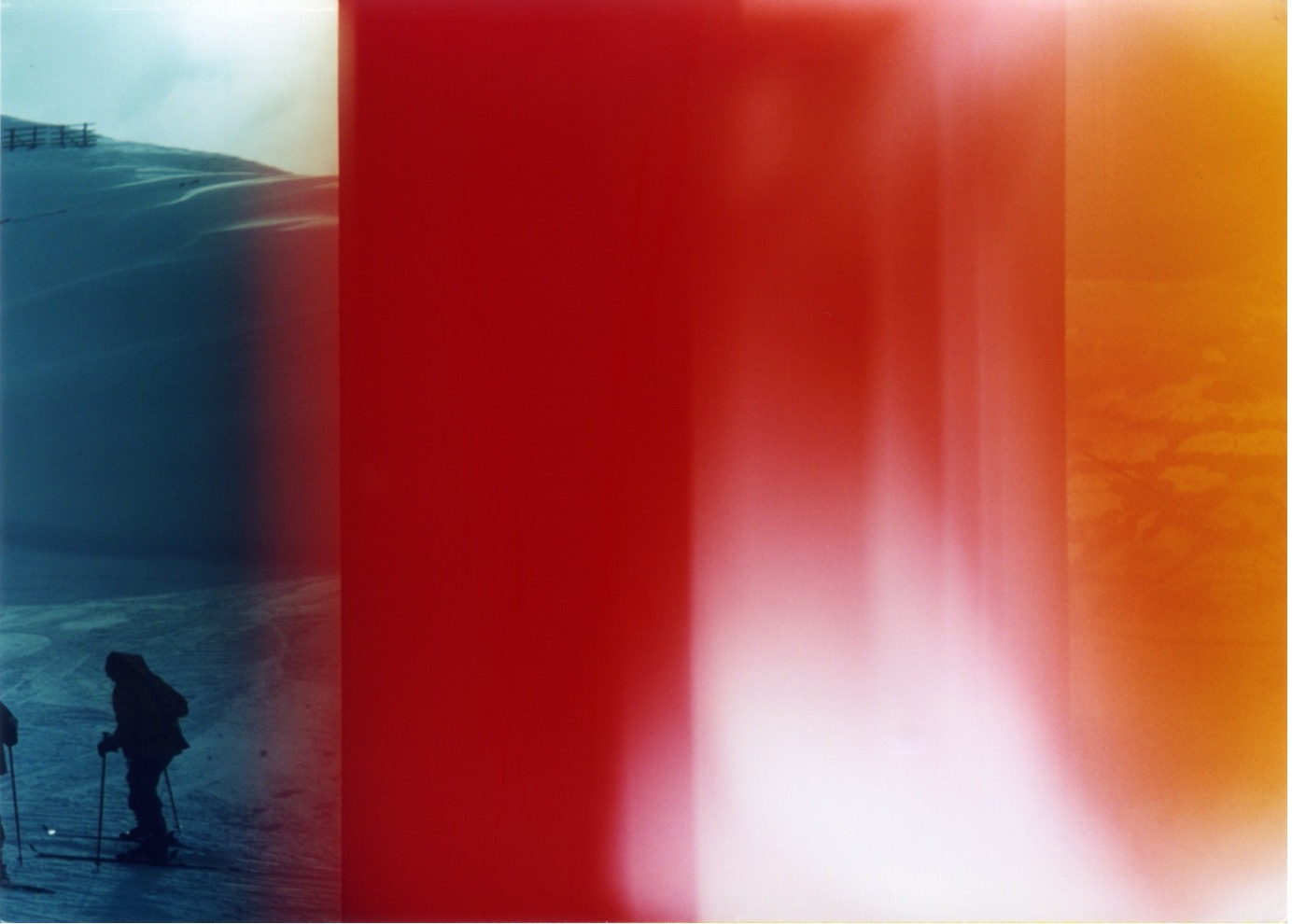

When I had last been in the city before the city had been grey and the work had been blue. My brother was working on an image for a show or a magazine, and the image fell out in hues of blue—two significant historical characters bathing in colour, represented as one hybridized face—and so, for the duration of the stay, work was blue in a city filling out with January’s grey. A mute grey: occasional flashes of burnt orange and ash; it always seems as though the light here is unusually sentimental.

*

Looking out from the window as promontory, the sun would pin irregular holes in between the adjacent buildings of mismatched age and the rain and the fog. Around midday, it would frame slurred constellations of colour that would sway, slightly, before giving way to the view. Shit constellations that distract, some.

*

Tangerine is meeting ochre.

The pink is coming up from the floor.

Seven or so in the morning, now.

Big broad road.

*

Adjacent to the building, there were facades that would run in correspondence—mirrors occasioning only flashes and glimmers of reflection. Recollected afterward, they were buildings that wouldn’t oppose one another, wouldn’t argue with each other, but make unremarkable conversation that could happily fill out the space in between them. Not historic, but not without some interest; not without some sporadic sense of comedy. It was the jokes that helped build a little parity between us, most of the time. We were overlooking a narrow avenue then.

The apartment we had sat and slept in didn’t belong to my brother but somebody else and was grey in that kind of plaintive empty way that always felt attractive, if a little cold; so, we sat there, quietly. Smoking quietly. We pull out occasional words from beneath each object of attention. I only ever saw the image on a screen twice. Once of a morning; once of an evening.

*

Driving a big broad road—

The light.

No stars.

A sunrise.

The image is a cocktail.

A sunrise.

*

In the frame we’ve Coco Chanel standing in front of or on top of or behind Vladimir Lenin; one, or both has issues with transparency and so their faces are merging into a single pair of eyes; a single pair of eyes that would peer out from behind these hues of blue and occasional magenta. They have become a single celebrity that looks like a range of celebrated actors from historical motion pictures. The chin is foregrounded by a gentle antique of a political jaw, the neck elongated by virtue of some now-famous pearls that would frame a face from the neck up. Knee deep in the complex plot of a money-maker, a special-in-serial for television. Huston or Welles. Lenin and Chanel shared in a year—1917—and their conflation marked some reference point for the formalities of radical change. Dirt road revolution. Set up in the one frame, they were two institutional hands—two museums pointing in different directions—but now, for a moment, they are looking the same way. Serving as some prefiguration to a meeting point determined by more than just a simple history, the image connoted a meal in a restaurant remembered after the bill. Dinner shared. Bread broken. Politics and fashion as two intermingling topics of conversation; a little confusion of political, emotional, and cultural capital, here everything would converge. I close my eyes. Put things in my mouth. We always liked to eat. Everyone was always eating. I watch the room move over your shoulders and we chew through our subjects; constellate our terms; conjugate our verbs. Skylight at night-time. Knowing that the stars are always ascendant things, we’ll strive to alienate the important ones and set them straight as a shelf of talismans. Point them out in a graded negative as they shine back to us; reversed on bone-white china. Dinner for two.

*

Bleeding colours now. The blue? A shifting political quietism. The pink? A picture of an audience’s attention span. In liquid crystal, the image fights its history and the screen lights some small arc around the image that blindsides the room as he spins the computer around in slow motion. Practical diminutions rather than any temporal lockdown, we’re not looking for any fidelity to a clock-time. The grey is giving way to a magenta and, falling down, the image fades to a puce with flashes of umber, embering again. The colour of The Financial Times, occasionally. Here and there.

*

We sat there for a time, me and my brother in a room; I was in the way so I walked out; couldn’t speak the language on the pavement, so would just walk through the afternoon, intermittently pause for a drink; let a drink feel like a piece of work. I was making lots of notes about audiences and about money at the time. About acknowledgment. About duplicity. About purchase and receipt. But light was the thing. Our sunrise was always artificial, meaning we could direct it where we desired.

*

When light is the thing, when light is sentimental, it becomes harder to fracture the real sense of cogency around the scene. The memory of it has a greater purchase. Owns it. Elucidating some things, censoring others. We’ll think more about our arrangement of it, its unfamiliarity. Any capacity to remember it right, recall it, feels like the more important thing. This scene has its protagonist, and the light spins on them; on the middle ground between us. This may be a fleeting contract, or it may not be. Whatever the case, it feels like an understanding. Heavily. We are talking two different languages but she speaks more of mine than I do of hers but that does not feel important. We are sat on a middle ground that’ll follow us, a foot below the car, hovering gently above asphalt that feels like it’s waking up. Destination wasn’t an important buzzword; it was the light that makes it by memory. The light humming as we work on rapport. A real experience of structure, or sentiment, or collective ownership. No script. Returns. No solo and all duet, it’s a push from word to word.

*

I shut a mahogany door behind me and sat in the first bar I happened upon at the street’s end. I had spoken to my brother there on the phone before; I recognized the predominant red of it behind his shoulders, framed on a little screen, the dark wood tables—the light, a plastic orange, would bounce off the red—I ordered a wine.

I’d told myself I was making way for a gallery; it was a couple of miles from the apartment, and I was walking there with no reason other than to see the city. There was an exhibition of pamphlets, poetry from Brazil from the late 1970s. Concrete work. Which already felt like the punchline to a joke that might get told tomorrow if it could find its way into some coherence. Find some anchor point to segue out of the colour of conversation and into this grey, pockmarked as it is with flashes of lightning; some way in which it could interlope as a referent for those shit constellations, proverbial or otherwise, these shifting colours of the day. My brother would tease me saying I was lighting out for material; it was cynical, but perhaps carried a shade of truth to it.

*

Maybe Victor Schklovsky could have his centenary here?

A foot above the shift of the road.

*

Defamiliar.

*

We are looking for a small room, and do not have much money to spend on it. Looking for another promontory. Looking to shut out an orange light as it turns down on its volume and looks like an ochre.

A burning colour.

Not talking about the middle of the day.

*

Victor Schklovsky first applies the word ‘Defamiliarization’ to his work in 1917; in 1917, in his essay ‘Art as Technique’ or ‘Art as Device,’ depending on who you listen to or depending on who’s talking. Under either title, Schklovsky is aping an increasingly popular stance advanced by critic Alexander Potebnya in his Notes on the Theory of Language some twelve years previous. They are both talking about repetition and about adaptation. Both talking on the idea that art amounts and that literature aggregates some ‘special way of thinking and knowing.’ That an engagement with culture proves tantamount to a ‘thinking in images,’ that it advocates some self-centred cognitive process predicated on an ‘economy of mental effort.’ A process of repeating oneself, picking upon prior patterns and trains of thought, of coercing new impressions into the coherent, running order of a logic picked up from an elsewhere. His is the quiet idea that reading underpins personality, and that each line demands relation to its predecessor. Demands its embeddedness in a heavy cache of older thoughts and ideas. A bunching up of the bedsheets. It all needs the logic of an imposed narrative order; Potebnya contends that the ‘relationship of the image to what is being clarified is that: (a) the image is the fixed predicate of that which undergoes change, and that (b) the image is far clearer and simpler than what it clarifies.’ The ‘purpose of imagery is to remind us, by approximation, of those meanings for which the image stands.’ We are standing for all our attributions, all of our associations.

Equating the claim that ‘art is thinking in images’ with our constant manufacturing or making of symbols, he attributes this mode to an old idea and argues that it survived its supposed demise, withstanding long after its heyday in the late-nineteenth century. Schklovsky argues that this conception of art and literature gives rise to the view that the ‘history of imagistic art’ is tantamount to little more than a ‘history of changes in imagery.’ The problem with this stance, however, is that the images change very little to his eye. From century to century, from nation to nation, from poet to poet, they’ll remain contiguous pictures; lessening maybe, or enlarged here or there, but the images are imposing themselves upon each other. Upon us. Vying for our eyeline. Our attention and priority. He can’t speak to the differences anymore. Their distinction. The possible alienation of like from like. This from that. Only sees the bleed. The blur. The problem with Schklovsky and his ‘economy,’ one that he would fatten out a little when he would come to pen a little excurses on love some years later, is that images belong to no one. As with any sentimental light, as sunrise; –set; or heavy dusk, possession seems remiss; connotes meet like the bleeding colours of a clock. Tangerine, pink, and ochre. Here, here and here.

*

A centenary for ‘Defamiliarization.’

*

The more you understand an age, the more convinced you become that the images a given speaker used and which thought his own were lifted or taken almost unchanged from somebody else. Work is classified or grouped as per the new techniques that a reader discovers, shares, and is parsed according to their arrangement and development of the resources of language. Each reader becomes much more concerned with the arrangement of images than with creating them. Images are given over to order; the ability to remember them seems far more important than the ability to create them.

*

As a picture of a boy doing impressions of a long-necked bird, I calmly stand with my head cocked down, submerged beneath the surface of some shallow depth of water.

*

I am sitting on a bench reading Schklovsky on my phone and self-identifying as a tourist who has not taken a single photograph since arriving at his chosen destination. The rain is coming down now, so I cut a line for some cover. Wanting to get off of the road, I walk into the botanical gardens. I hide under a canopy. Buy a coffee for 60 cents.

The garden itself was an inimitable push for analogue. It doesn’t bloom but looks like a monetary system. A personal economy of arranged elements. An arraignment of heavier symbols. A little carnival for the quieter ones. A reminder of Schklovsky’s work; the remainders of a gardener’s work, thinned out. A memorial to money spent. A bad joke about Monet. About flowers. About time.

The rain would ease up a little and, walking through, it was the camellia japonica that would come up. A veritable rose of winter, it would come up though the scene was something to talk to; emboldened, it outstrips itself of its own vocabulary, colouring the words in a vulgar pink. Grotesque within expectations of colour and a want for primaries as a puritanical drive in January’s call for some elective value; this month has its eleven cousins. Here, they all compete for some attention. Looking at the japonica, the japonica looks like a Navajo necklace. And if turquoise is a thing that symbolizes little more than its hard-and-fast opacity, this’ll be a coral-pink, meaning history, but only in the vaguest sense of the word.

*

The proper distribution of light being a shared commitment, this time it’s only you in the frame; we can look to share in that. Share in that picture. We paint a picture of a protagonist as a moment of collective action: we’ll pick their active verbs. Their doing words. Tangerine is meeting ochre. Will live on that middle ground for a number of hours. Do and be.

*

In the garden, I would be thinking backwards. About family dinners in Texas, about early memories of other cities in the rain. In San Antonio it is raining. Pointed fingers formed of glass. A point made, then broken, then dispersed—a semblance of idea now flat across the floor in reservoirs of association. By memory, we are leaving a restaurant: we are leaving a restaurant and we are running for a car; we are running for a car amidst the rain. In my mind, the restaurant could be recollected as a cavernous space; predominantly, or, permanently dark. Obtuse and twisted around itself. An envelope or a sailor’s knot. This darkness would expand the architecture of the scene. Inevitably and invariably. Not being aware of the room’s defined parameters, it would continue—on and on—an endless array of numbered tables and chairs. It is a dark room, it is breathing with crowd: an undefined number folding in, out, and in on itself. Conversation reverberates. When thinking of the restaurant, being only a child then, all I could remember was the darkness of it; the darkness of it, the breadth of the table, and a jar of honey shaped as a small bear posing as a small boy.

*

Driving back from that hotel in the morning you tell me the radio is sounding out something and it sounds like something straight out of a Howard Hawks film. Dressing up this little year in my own false nostalgia, you tell me that before I can get there. I remember how young I am; I try my luck for something funny to say.

*

Walking the avenues of the garden there was a bust on the east side of the central house, settled back in the left-hand corner of the square. A metal mountain. Ruben A.: a writer, under pseudonym, shown here from the shoulders up and cast in metal. A bust. Ruben A.; Ruben Leitão. Little pig. A dead man of letters in some ignored gardens. Ruben A., 1920 to 1975. 55 years of life. 20,075 moons. Leitão, born in Lisbon—May 26th, 1920—would die as two people in Lisbon—September 23rd, 1975. A., a writer, a novelist, essayist, historian, critic; author of several notable autobiographical texts, A. would write under a pseudonym; his middle name as a middle ground; A. was one thing, Leitão was a different animal. Some kind of bird. A., perhaps a pelican; his head dressed in water from the neck up. Ruben A.: distanced from his time playing his part as a professor, 1947 to 1951. As Leitão, A. is looking at Leitão—another character entirely. An official at the Brazilian Embassy, ‘54 to ‘72. A. is a train of rhetorical miles; the distance walked away from the work of an esteemed politician to the quiet preoccupations of poetry. The remoteness of two glyphs. As between A. and B.; as the gulf between me and thee. Leitão is watching Leitão pace the garden path. He is considering what would happen when his eyes and mind would be so anchored to a single spot. Antecedent to his statuesque status, he is imagining Ruben as a quiet star. Not a useful Polaris, but mythic; Gamma, Delta 1, or Epsilon. A point of light fighting the point and perspective of its place in a constellation, in conversation; consoling itself with its own selfish little light. Its occasional power to illuminate a given thing. Indicate a given way. A direction or rubric for living. Leitão’s pseudonym—his letter—felt locked in on Schklovsky’s track somehow. A. was representative of an effort-apparent to disrupt the logical progression and development of a given name and, instead, sit in a hiding place under a sole initial. Under the romantic colour of a quick photography. The perspicacity of a polaroid, A. was tainted by the imposition of a frame and the qualities of a machinic photometry when sat here in metal. A. was perhaps here a memorial for self-invention. A limiter for exposure. A remote control for the small hours. Click, click, click. A portrayal of the lessening minutes of a life. He had to change his name in order to reframe his memories; cast them as material, recast himself as more fodder for a reader’s arrangements. As a little pig primed for slaughter. A. was breakfast. Was bacon. Was a theory of defamiliarization. An assured assertion of ownership. A marker for the qualities of a place rather than the virtues of a person. A figure on his own, flanked in this orange hue. Rendered still with an alchemical fix. Confused by the private money that grounds him now, shot through with damp terracotta—and raked in light—here his face is prefigured as a constant party to those very shit and fleeting constellations he was here excluded from. The ones above. Overhead. They felt like things below. Here, markers for the mud. Here, Autumnal leaves. He is counting out their various points of light, now. These constellations. Renaming them for his own purposes. Naming himself after them, point for point. Their various ideas and insinuations. Maybe I was green for his anonymity, envious of his repudiation. His invention of a closed system of things around an invented name. A., an asterism. It was hard to tell. The copper had oxidized some; gone green. I guess I was a little jealous. A mirror for the garden’s own ideas of itself.

*

Small fireworks now, we’re reaching for a cord to pull on a lamp; room on a third floor in a cheap hotel; the short, orange light of a roman candle or a machine sensitive to low light, we’re primitive like a candle now, more or less. Primitive like a candle.

*

I was thinking about A. on the morning of January 1st. We were on the road, had been, and were driving out of town around seven in the morning. We had been looking for a hotel for around an hour and had cut a path away through slow and slurred conversation as the nighttime gave way from a deep blue; to pink; to orange. Finding some consolation in the little constellation always apparent between a driver and a passenger, we could do nothing but build on from there. I had only known her for around an hour, but there was a connection there that couldn’t be dissected and so it felt like we had to be honest with each other. Ours were investments in that mental economy, trying to settle an exchange rate for emotional capital in the apparent sentimentality of this orange light at seven in the morning.

She had asked me something about films, something about the importance thereof; I thought about Schklovsky, and the totalizing tendency in his notes on cinematography wherein he would so declaratively talk about cinema. A total of maybe eight or eleven films had been made when he would put pen to paper and the book would find publication. Time, on his side, allowed him to total his commentary like a car. Where he could swing a sweeping hand, with precision, now his comments were lost to generalization. If defamiliarization was now one hundred years old, we were trying to run under the weight of its centenary. Of that invented sense of precision. We were looking for that general feeling amidst the specifics of detail so we could run with the minor differences. Celebrate them. Forget about certain things, commemorate and communicate others. Too much education, we proclaim and raise our declaratives—after Schklovsky—and think a little about the various definitions of dedication; a little for you, a little for me. Tangerine and ochre. At this point, I’ll keep my mouth closed.

*

RUBEN A.

Poor Redundant Algorithmic A/ Old, rotund, retiring A./ reminiscent A., and his notional nostalgia/ Randian A./ Ruling A./ A. is failing now as a relinquished A./ A. returns, recollects himself, and reminds himself of A./ A remuneration/ A remonstration/ A Raw A., for a Ritalin supposition/ A remembered A., for his relatives and others/ A rotten A., chewing on some cliché played out on the woods, the trees, their fruit/ a Roman A., for the mythmakers/ a Royal A., for the range/ A., a Roman á Clef/ a novel with a heart, ripe for adaptation/ turning out as a first-rate film/ A., a round of applause/ A., a critic’s adulation/ Whilst spinning out the many ratiocinations of A., A., now romantic, would see a version of A. romance nothing but a mirror image of A./ would see nothing in the merging middle ground between A. and Leitão but a representative, rewritten name coming apart as a single character/ a glyph/ an A./ A. is now renouncing himself/ A. wants to re-emerge as another A./ A. is unrecognizable to himself/ A. wants to be reoriented/ reiterated/ be remembered, but selectively/ be recollected as an award-winning A./ A Recidivist A./ Racemic/ A., a thing resolved/ A resolution/ The Mexican Revolution/ Rheumatic Ruben/ Ruben A./ an A., waiting to be eclipsed by the logical progression of an alphabet…/ A, and on/ A., and on/ A., only after the glean of a mirror image/ An echo/ A train of A’s in a graded delay/ A., seeking returns on Saturn/ A., Looking to see himself in middle distance, in the muddy mid-terms of a compromised reflection/ A. can think of nothing but his own continuity/ A, and on/ A., and on/ A., only after the glean or glamour of an open door/ an open hour/ A. is unrecognizable to himself.

*

The day has its contracts. The incorporation of a morning as it so insistently joins hands with an afternoon and goes into business with the evening; withdrawing some details, talking over others, this is escapist rather than censorial. The joint work of the hours. The day’s business.

*

I would write to her later that month and she would write to me later that month and tell me about a fire on a beach; tell me that my face was changing constantly during the night. She would tell me she sat with the fire until it was a little dark, and then leave the beach. Were we two mirrors? Looking for a little middle ground? Looking to define our terms and round out the difference between some mathematical recompense and a cheap poetics of escape? A mirror looking at another mirror; There was a value in that that could keep us talking. The various definitions of escape. Of bouncing light. Its contexts and its necessaries; the absence of its closure. Bouncing light in an early morning car.

*

Running remarks on a centenary for the defamiliar.

*

But the sentimental light…

There are orders of candles, set against personal activity.

*

I hold a candle.

I am lighting a candle to you.

I burn a candle;

I am burning a candle at both top and bottom.

*

Francisco de Sá de Miranda

‘what can you do when everything’s on fire?’

ENDS

‘January 1st (Ruben A)’ is the first in a series of 36 photographs and correspondent texts in a collection titled 36 Exposures (forthcoming from Dostoyevsky Wannabe). Over the course of a single year, Houghton would send Jaeckle three photographs a month from his archive; Jaeckle would respond with an accompanying prose-work for each image. At the year’s end, the resulting collection would cover twelve months, comprising 36 images and 36 reactions, and express itself as a roll of film in the abstract. A contact sheet spoilt by written interventions; an index of distractions and elaborations; an array of materials that pictures a false or disrupted communication as ideas are exchanged and images developed over the course of a calendar year. From the onset of the project to its end, Jaeckle and Houghton never met in person—this exchange of materials was their only means of communication—and thus, this collaboration is a form of conversation twelve-months wide and three-hundred-and-sixty-five days long. The texts number fragments, at turns essayistic and anecdotal; short stories, prose-poems, and assimilated citations. The images are largely personal: snapshots; familiar faces; passing objects of interest and attention. Whilst each text in the series was prompted by a single image, this publication of ‘January 1st (Ruben A)’ features an additional quartet of photographs from the same roll of film that carried the first image in this suite, the initial and only basis for Jaeckle’s first response to Houghton at the onset of this project.

Hoagy Houghton is an interdisciplinary artist based in London. His artwork is autobiographical, drawing on observations of the melancholy and humour in everyday life.

Dominic J. Jaeckle is a writer, editor, and broadcaster. Jaeckle curates and collates the irregular magazine Hotel and its adjacent projects (partisanhotel.co.uk), and runs a minor publisher, Tenement Press (tenementpress.com).