Jennifer Croft’s Homesick (Unnamed Press) is a coming-of-age story of a girl named Amy (based closely on Croft) growing up in Oklahoma, homeschooled, and whose childhood is branded by her sister’s diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Combining text and photographs, the book might also be described as a sort of photo album tracing the sisters’ childhoods. Each medium—language and photography—elucidates the other, carries meaning that is impossible to convey otherwise.

The cover of the book, with pastel blue mixed with strokes of yellow, red and black colliding in this fusion of dreamy, abstract-like painting, the title in bold in the dead-center, is a lovely representation of Croft’s impressionistic style. On the very first page there is a seemingly random photograph of Pont des Arts,shot from a distance and from behind glass. On top of the image there is a red graffiti note—but just a few letters, making it impossible to comprehend. From there a story of images unfurls: on the next page a picture of mountains; a child’s drawing of a house on a white wall; a window, shot from the outside of a house, slightly opened, inviting, pink curtain obscuring the view. Underneath the images are lovely, disconnected musings—which only later does the reader piece together to be a letter from Amy to her younger sister, Zoe. The letter could only be written years later, once there was distance from their childhood, the trauma, the guilt.

I caught up with Jennifer Croft the day after Olga Tokarczuk—whose book Flights had been translated by Croft—was awarded the Nobel Prize.

Nataliya Deleva: Jennifer, I’d like this conversation to explore a kind of translation not of one language to another, but of language carrying the meaning of childhood memories—of conveying trauma. More time needs to pass before Amy can understand all she’s done throughout her life to protect Zoe, to “capture and fix forever the presence of her sister, to contain her, to never let her go, or break, or even change”. It’s fascinating how the book dances between text and visual image: photography demands distance between the photographer and the object; and in your book the narrative is brisk, in third person, told in a matter-of-fact manner: there is, so to speak, distance between the narrator and the described events. Considering this is a memoir, and one telling a very personal story, I found this decision surprising at first. But then I wondered if the distance in fact allows for a wider view, almost as if the narrator is an outsider to the story – something you needed, perhaps, in order to tell the painful events. Was creating this distance more important for the narrative and the way it unfolds, or for you as a person trying to heal your own trauma? Or, perhaps both?

Jennifer Croft: Each of the very short chapters in the book is a kind of Polaroid snapshot, a vignette that captures just a flash of emotion, which I like because it substitutes that wonderful white space a Polaroid has around it, where the viewer (or in this case, reader) can fill in her own feelings and ideas, for the rumination or more theoretical flights of fancy that take the reader away from the main narrative, or else weigh it down. The subjects of the book are already heavy, so a lightness of touch in the prose was one way to help the reader get through them.

There is also distance between what the actual photographs show and what story the text tells, which evolved in a more gradual way. I originally wrote the book as a novel in Spanish while living in Buenos Aires, and in that version, the language is at once very familiar and very strange, since I started studying Spanish only in my mid-twenties, which means it still sounds foreign, but I also only ever studied Spanish in Buenos Aires, which means that my Spanish is also instantly recognizable as local. For the Argentine reader, the prose itself triggers a sense of suspense from the very first sentence. Who is this character locked in a closet while tornados roam the Oklahoma plains who nonetheless is speaking in this strange, familiar way?

The English version could not reproduce that effect exactly, for obvious reasons. So I spent a couple of years trying to come up with a strategy that might create a distance that would encourage the reader to forge ahead, to cover the territory Amy does in order to see her off into the world.

ND: I might say (although you might disagree) that your whole book is, in essence, photography. You open the lenses of your memory to allow the light in, which you then redirect onto the surface of the page and reflect through text, leaving sharp representations of the past events. Images not only supplement and contextualize ideas; each fragment, sometimes as long as half a page, is in itself a textual snapshot, a slice of time (as well as space). The text resembles the Hansel and Gretel’s path of crumbs: each time you encounter a piece, the next one emerges from the darkness of the past, and you have to follow in order to get to the end. You re-order and reconstruct reality with each image and fragment, reminding me of what Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography: “The camera makes reality atomic, manageable, and opaque”. The faceted structure allows or even demands the reader to assimiliate a single event at a time, and leaves open the question how to interpret the whole. I wonder what your reason for this structure was—did you find it more manageable, or even necessary, to write about your past that way?

JC: The girls read Hansel and Gretel near the beginning of the book, and that is also an important structuring guide for their story, particularly for Amy, who tries so hard to protect her sister and leaves all these crumbs she thinks will allow them to get back to where they started, to this idyll she imagines based on the summers they spend together in the beautiful, verdant semi-wilderness of Oklahoma, before Zoe gets sick. But of course there’s no way for them to ever go back to before Zoe’s illness, just as even the healthiest of siblings inevitably lose some of their initial closeness as they age. Homesick argues that Amy’s strategy of photography goes hand in hand with that kind of delusion, or at least wishful thinking, whereas translation, which she discovers later, is a more dynamic way of relating to others while maintaining true intimacy and connection.

ND: Have you read Naja Marie Aidt’s When Death Takes Something From You Give It Back: Carl’s Book? It is also a beautifully written memoir, though very different in form and style from Homesick. In both books there is pain—just as you expose the wounds so they may heal, so does Aidt. But in contrast to the distance you’ve created, she takes a very different approach, perhaps because she writes the book while experiencing the raw grief: faced by the sudden emptiness of language, she finds solace in quotes from other writers, poems written by her sons, notes in her diary. The silence between the lines, the meaning that sprouts from the unsaid, is something else in common. You employ the image of an octopus as a metaphor of the unsaid, the untranslatable. Amy begins wishing “we could be octopuses, so we would not need words.” The octopus is also the ‘safety net’ that Amy clutches to when in despair, carrying her octopus toy with her.

JC: I haven’t read that yet, but now I’m even more excited to! One of the books that influenced me was Romina Paula’s August, which I translated from Spanish for The Feminist Press shortly after I wrote the first draft of Homesick. It, too, is more raw and more explicit than my book, but it was a helpful way to start thinking about grief in adolescent girls and how mourning can become almost a separate physical presence—almost another person in the room—that also changes over time. Paula does leave a lot unsaid, as well, not giving the best friend who committed suicide a voice, and this was also something that interested me, the journey that Amy takes just to reach the point of actually listening to Zoe, after a lifetime of trying to teach her things, “civilize” her and protect her.

There were certain images for me that did become crucial as I worked, like spirals, which kept cropping up in the pictures I found in old files and which felt like the perfect way to think of the sisters’ movement through the text. On the one hand, they are both progressing in their lives, but on the other, they keep coming back to each other, as one of the captions says, “like the intertwining spirals of our common DNA.”

ND: It’s interesting what you say about Amy somehow moving towards that moment of learning how to listen to Zoe, as opposed to teaching her and protecting her. I guess this instinct is in all of us older sisters. But I wonder if there is another feeling entangled in this late realisation—namely, guilt. To what extent was guilt a driving force for Amy? I recently completed my second novel, which is in fact part fiction, part memoir, and which also narrates a childhood trauma. It took me more than fifteen years to feel strong enough to start writing: I had to free myself from the subconscious self-restriction I was terrified that by writing about my childhood, I would evoke and even re-experience the nightmare events from those early years. But as I went deeper and deeper into the process of planning the book, I approached the very core of what had branded my whole existence and influenced my adult choices—and that was guilt. In your memoir, throughout the many traumatic events Amy experiences, the guilt is constant. She feels guilty that she is the well child, while Zoe is the sick one; she feels guilty that Sasha, who Amy has fallen in love with, takes his life; she feels guilty that the terminal children in the hospital die because, in her mind, they’ve lost the game against Amy. And so on. This guilt – as the root of trauma – is something that people cope with differently, but in every case the healing can’t happen until you’re aware of, and subsequently expose, the guilt– whether in a conversation with others, in a text like this one, or even self-reflection.

JC: I wrote an essay recently about translation and the work of individuation I had to do in order to become a well person despite my sister’s illnesses called “The Daily Alchemy of Translation.” This involved working out my guilt around speaking in someone else’s stead in translation, too. It’s a tricky thing since it implicates empathy as an almost pernicious force, but too much identification with another being did prove almost fatal for me.

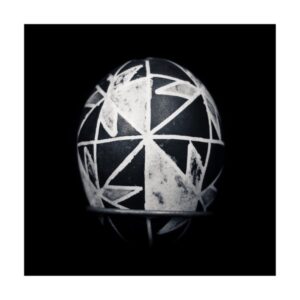

As I mention in the essay, Buenos Aires (where I wrote Homesick) has the highest density of psychoanalysts of any city in the world. I was inspired to do a year of therapy in Spanish and found it incredibly helpful to think about the events of my childhood and adolescence in a language different to that in which they originally happened. It stripped everything down to its essence, making it possible for me to understand in a way I never had before. In Homesick, I write of Amy’s early travels that “[i]n country after country she will calculate exchange rates and learn words, lie when she’s missing the words for the truth and be lighter in translation because all words without memories are beautiful and hollow like the eggs Amy and Zoe used to dye each Easter that Zoe always tried so hard to keep from breaking.” I think of fresh words and their relationship to memory like this (also taken from Homesick, a photograph I took in Ukraine):

ND: This ‘essence’ is, I think, so well captured in the letter that Amy writes to Zoe underneath the photographs. “Oh Zoe, what does it mean to have already done something you know you’d never do?”, and then: “It’s so hard for me now to understand myself then, which makes me want to trace things back to where they started, and sometimes I wonder if it might have been that afternoon I burned my black dress in the sink.” But I had the sense that the text and the image flow in the opposite directions: while the story-in-photos starts from the early childhood years, the story-in-text underneath the photos streams back in time, from the present moment towards the past. The letter feels almost like a self-therapy session–the only way to understand and heal is to go back to your past and re-experience it. The two narrative threads move towards each other. And just as “when a Russian word meets an English word, it creates a spark”, as you write in Homesick about the translation process, these two narratives explode when they meet; this is when Amy realizes: you cannot undo death, all you can do is to connect. I think form is such a critical part in conveying the narrative. I’ve always been drawn towards non-linear structures. I was fascinated by Jane Alison’s book Meander, Spiral, Explode – a book in which she imagines alternatives to the Aristotelian progression of beginning, middle, and end. It makes you view texts in a completely different dimension.

JC: Yes! While the vignettes take the form of Polaroid snapshots, the whole is a double helix. It’s Yekaterina Gordeeva and Sergei Grinkov spinning on the ice, clasped in each other’s arms. It’s how texts (original and translation) that are in permanent relation to one another, totally inextricable, and yet perfectly separate and distinct.

Jennifer Croft is an American author, critic and translator who works from Polish, Ukrainian and Argentine Spanish. She was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in 2018 and a National Book Award Finalist for her translation from Polish of Olga Tokarczuk’s FLIGHTS. Croft is the recipient of Fulbright, PEN, MacDowell, and National Endowment for the Arts grants and fellowships, as well as the inaugural Michael Henry Heim Prize for Translation and a Tin House Workshop Scholarship for her memoir HOMESICK. She is a founding editor of The Buenos Aires Review and has published her own work and numerous translations in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Granta, VICE, n+1, Electric Literature, Lit Hub, BOMB, Guernica, The New Republic, The Guardian, The Chicago Tribune, and elsewhere. Croft is currently translating Tokarczuk’s novel Księgi Jakubowe (The Books of Jacob), that won the Nike Award in 2015.

Nataliya Deleva is a Bulgarian-born writer living in London. Her debut novel Four Minutes (www.fourminutesbook.com), originally published in Bulgaria as Невидими (Janet45 Publishing, 2017) and then translated and published in Germany as Übersehen (eta Verlag, 2018) won the Best Debut Novel Award and was shortlisted for Novel of the Year in the most respected literary competitions in Bulgaria. Deleva recently completed her second novel, which is part fiction, part memoir, written in English. Twitter: @nataliedelmar