Lawrence Rinder

Most people who know of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha know only her remarkable book, DICTEE, published in 1982 by Tanam Press. This marvelously unique work—which combines poetry, calligraphy and other manuscripts, found texts, diagrams, and photographs— has become a staple of many university literature and postcolonial studies courses. It is one of those rare works of art that have the power literally to alter people’s lives. Through its appeal to the senses, to memory, and to a multiplicity of resonant cultural touchstones, DICTEE takes the reader on a journey that has left many with a feeling of almost alchemical transformation.

Yet so little is generally known about Cha or about her extraordinary literary and artistic oeuvre that the author of DICTEE may seem to most readers to be elusive or nearly anonymous. This state of affairs would not have been anathema to Cha herself, who in virtually every work she made sought release from the limitations of the individual ego. Deeply informed by Confucianism, Catholicism, Buddhism, and Taoism, as well as by postmodern theorists such as Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, Monique Wittig, and Jacques Derrida, Cha’s works constitute a pioneering exploration into the nuances of intertextual, omnimodal, multicultural identity.

This issue of Fence presents a group of Cha’s poems, published for the first time, as well as photographs of several little-known works in other media. The poems and many of the visual works were probably created during and shortly after her highly productive 1976 sojourn in Paris, during which she studied at the Centre d’Etudes du Cinema Americaine à Paris. It was in Europe that she immersed herself in a number of intellectual and aesthetic currents— French film theory, feminism, and an Icelandic version of Fluxus known as S¥M—that became centrally important in her subsequent work. What is immediately evident in the small sampling presented here is the profoundly interdisciplinary nature of Cha’s art and writing, an approach that will be familiar to readers of DICTEE. In her extended oeuvre, however, we can see even more clearly Cha’s highly conscious manipulation of form and mode to achieve subtle nuances of aesthetic and poetic effect.

Happily, simultaneous with Fence’s publication, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, home to the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha archive, will present a retrospective exhibition of Cha’s art that will travel to New York City; Seattle; Irvine, CA; Urbana-Champaign, IL; and Seoul, South Korea.

Juliana Chang

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s artwork materializes haunting and evocative qualities. Many of the images and words in DICTEE, for example, arise from an elsewhere that we cannot easily name or locate; her texts are often presented as remnants, traces of an other time. In her videos, words may dissolve into other words, or disintegrate into fragments, then reemerge. To encounter Cha’s work is to come up against the uncanniness of the symbolic order— its strangeness, but also its insistent familiarity. If we recall that one’s unconscious does not wholly belong to the individual, we might begin to grasp Cha’s approach. Her use of language and images evokes a sense of impersonality, because they seem not to derive from or pertain to a knowable individual subject with whom we may readily identify. Yet from within this disorder or mystery, we experience her writing and art as powerfully resonant. Cha’s art speaks to us not at the level of a coherent sense of self, but at the level of our unconscious: our memories, dreams, fantasies, desires. As Cha shows us, this unconscious is not purely personal, but is constituted within a web of larger forces: the violence’s of imperialism, the displacements of modernity, the lure of cinema. Nor is Cha’s emphasis on the symbolic wholly incorporeal: We encounter in her work the stain of blood, the orifice of the mouth, the organs of speech.

At one level, Cha’s work presents us with a crisis of symbolization: We cannot resort to formulaic notions of history, language, identity, or experience. But a crisis is also an opening: Her texts create an uncommon beauty from shards, splinters, and remnants. As Juliana Spahr notes in Everybody’s Autonomy, writers and artists like Cha demand new practices of reading and spectatorship. Rather than demanding that we master the text as something foreign and opaque, Cha’s intertextuality allows us to encounter our most intimate selves as this alien and ghostly other.

Juliana Spahr

Recently Thalia Field sent me an essay, for a collection I’m editing on poetry and pedagogy, about how she likes to give impossible assignments. What she finds valuable about them is their openness to the aleatory, the accidental, the reconfigured, the random as well as the related. Impossible assignments allow the classroom to arrive at a new place, to escape conventions. In this sense, the term “impossible” is useful when teaching a work like DICTEE. Whenever I present this book to students, it requires me not merely to admit that as a teacher I do not know everything; it also encourages me to teach toward those spaces I do not know— to see these productive lacunae as the point, not the afterthought or the guilty admission.

When I teach DICTEE, I begin by talking about what is possible and what is impossible for various readers. We examine DICTEE as a work written out of postcolonial and minority immigrant experience, which is nevertheless unlike most of the literature categorized as representative of these experiences. Cha’s text is built around discomfort. It offers little reading ease. It often teases and inspires readers to question what they take as proper, correct, or true, and gives false information— both obvious and not so obvious— along with verifiable facts. It addresses domination in many forms: the Japanese occupation of Korea, the internal colonization of immigrants, the self-perpetuating privileging of dominant culture over minority cultures, the demands of teachers over students, of men over women. DICTEE is marked by shifting and variable degrees of “accessibility,” in that one’s ability to read this work in its entirety depends on mastery of English, French, Korean, Chinese, Ancient Greek, and Latin, as well as one’s ability to recognize the book’s uncaptioned pictures.

All this asks students to think about what they know, and why and how this knowledge changes the act of reading. In order to begin with these questions about impossibility, I often have students form small groups to map the chapters of the book on butcher paper. I ask them to list the documents and approaches included in each chapter, and to mark in different colors what they as a group know and what they do not know. Then together we assemble on the board a composite map of our readings. Each class produces a different chart, but taken together these diagrams are a testament to the sheer varieties of data in this book.

From this point, I concentrate on DICTEE’s refusal to be English-only. I have the monolingual English speakers attempt the research necessary to understand Cha’s other languages. They use dictionaries, but also, more important, they go out and talk to other people to discover what is being said in the non-English passages. From this attentiveness to the limits of English-only knowledge, I find our discussions of DICTEE enriched with a sense of ethics. In other words, by beginning with linguistic impossibility, we are better able to hear what this work has to say about nationalism, about immigration, about difficult belonging, and about reading, and communication itself.

Walter K. Lew

In 1983, the “Clio History” chapter of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE was published in a group of pamphlets by various authors, titled PARTIAL TEXTS: ESSAYS & FICTIONS, that forms part of the since-neglected artistic and political context of Cha’s innovations. Except for the quotation from “Paths,” the passages below were all picked from PARTIAL TEXTS and arranged by Me-K. Ahn, Eura Chun, Eleana Kim, and Walter K. Lew one evening at a Mindeulleh Youngto cafe in Seoul.

Clio & Historiography

1 .

Two sisters wearing polarized glasses and separate hearing devices, and watching different television programs on one system.

2.

Semblance thrives on the destiny of divided purpose.

Sentiment as emancipated reference raised to the oblique power

3.

For this time, however, the pure, magical states (before any “making” even begins), the artist, given the gift of Medium, partaking in transformation processes, captures eternal wonder. I cannot help but to express the overwhelming sensation that almost resembles a returning, an abandon, a salvation from the struggle of being human, to only the purest of pure

4.

The removal of . . . unscientific doctrine that good or bad genes are the monopoly of particular peoples or of persons with features of a kind will not be possible, however, before the conditions which make for war and exploitation have been eliminated.

5.

Patricia: How long will we be as bloody and dirty as children?

[…]

Father: Your statements are reactionary cause you can’t so simply put ideals on top of what’s actually happening to you. If this society in which you’re living shits, you have to shit.

Patricia: But ideals can pick holes in the social fabric. ‘True’ and ‘false’ is besides the point. Even if they did nothing, they’re the only tools we’ve got.

6.

that political meaning is nascent at all levels of social relations (not just world affairs or “current events”); that the emergence of a radical political language entails an awareness of and a transformation of the forms of writing and codes of communication; and that there is now an urgent need for a reevaluated and revivified political consciousness within language itself.

7.

rendered incessant, obsessive myth, rendered immortal their acts without the leisure to examine whether the parts false the parts real according to History’s revision.

8.

from the apex comes a continuous stream of heads without bodies. Faces from every history speed furiously down the tunnel, some glancing off my windshield. One stops, a pale Persephone, like a bee hovering. A moment of eye contact through the glass and then she accelerates to past. It is fast in this era, there is no time for these dismembered shades to stop and tell their stories, to ask of their sons and daughters

Works By Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

Cover

Aveugle Voix, performed at 63 Bluxome Street, San Francisco, 1975 (rehearsal at the Greek Theater, Berkeley) +

Back Cover

Untitled (Audience Distant Relative), 1978

Text stamped in ink on six white envelopes 6.25 X 9.5 inches each

Insert

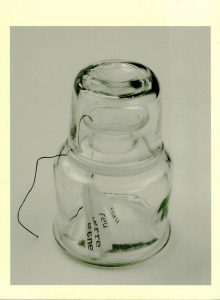

Untitled, 1980

Glass jar, thread, typewritten text on paper

3 X 2 X 2 inches

Gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation and Noelle O ’Connor

Untitled (VIDE), not dated*

Untitled (pearls), not dated

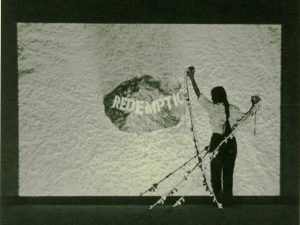

Image from an untitled slide installation

Untitled (wash wash exhale), not dated*

Untitled (recit), June 1976*

Other Things Seen, Other Things Heard (Ailleurs), performed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1978 (rehearsal)

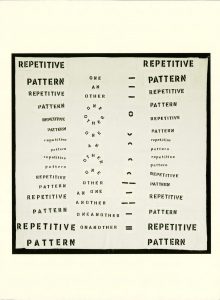

Repetitive Pattern, 1975

Text and symbols stenciled in ink on cloth strips, sewn with thread on cloth

46 X 46 inches

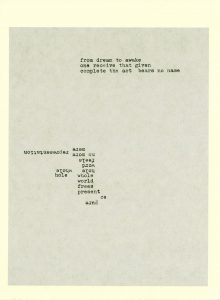

Untitled (from dream to awake), not dated*

* photographs by Benjamin Blackwell

+photograph by Richard Barnes

+ photograph by Trip Callaghan

Special thanks to Stephanie Cannizzo, Curatorial Assistant, who selected these works from the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Archive.

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2001 issue of Fence.