There was something so moving about how they would recede. The figures would waver in the vaguely human-shaped but more-than-human, larger-than-human, portals in the heights of the dome to take their fill. I would watch them come forth, lean out, gape. Their faces in gray distance visible as tiny, skin-colored moons set above the hues of their clothing. The eyes not there at all. So, from what I could make out, they were blank moons.

Yet those eyes must have been everything. They were taking in an immensity before, in a few seconds, or in some cases a minute or more, the little moons and the colors below them would sink backward into the shadows. I would watch them make their circuit of the universe. Slip into one body-gap of stone, command a facet of this world, then retreat, dissolve, and manifest in another portal. It must have been something to see all they saw in those clips of witness at the compass edge, to possess their brief, parceled vantage onto everything.

But from down here, there was only the sadness of repetition. Of more of them coming and going. Of each one sending its gaze, then dissolving. Then reviving farther along the circle. So I could follow the swatches of khaki or red or cobalt becoming undeniably real, before slipping back again and again. All day they were at it, taking their moments. Then ebbing and reappearing, then vanishing for good. While I had one long series of their unending returns.

*

We’d rented an apartment on the first floor a few streets below the butte of Montmartre. In the evenings sometimes my wife and I would walk up the railed steps and mill about the cathedral with the crowds. There was brash English hollered by Americans; smaller voices melding accents or searching for “pardon”; the complaints of children who desired Italian gelato but not Sacre-Coeur; and, here or there, still presences of carefully dressed women or men who stayed silent as their families shouted or jostled the crowd. The quiet reverb of these people brought our eyes. They seemed conscious of the gazes of others. They would examine their families as from the perspective of an outsider already annoyed, beset by layers of humanity adding nothing but more—more demands, loud hungers, more certainty this was the place they needed to be because so many others had found it.

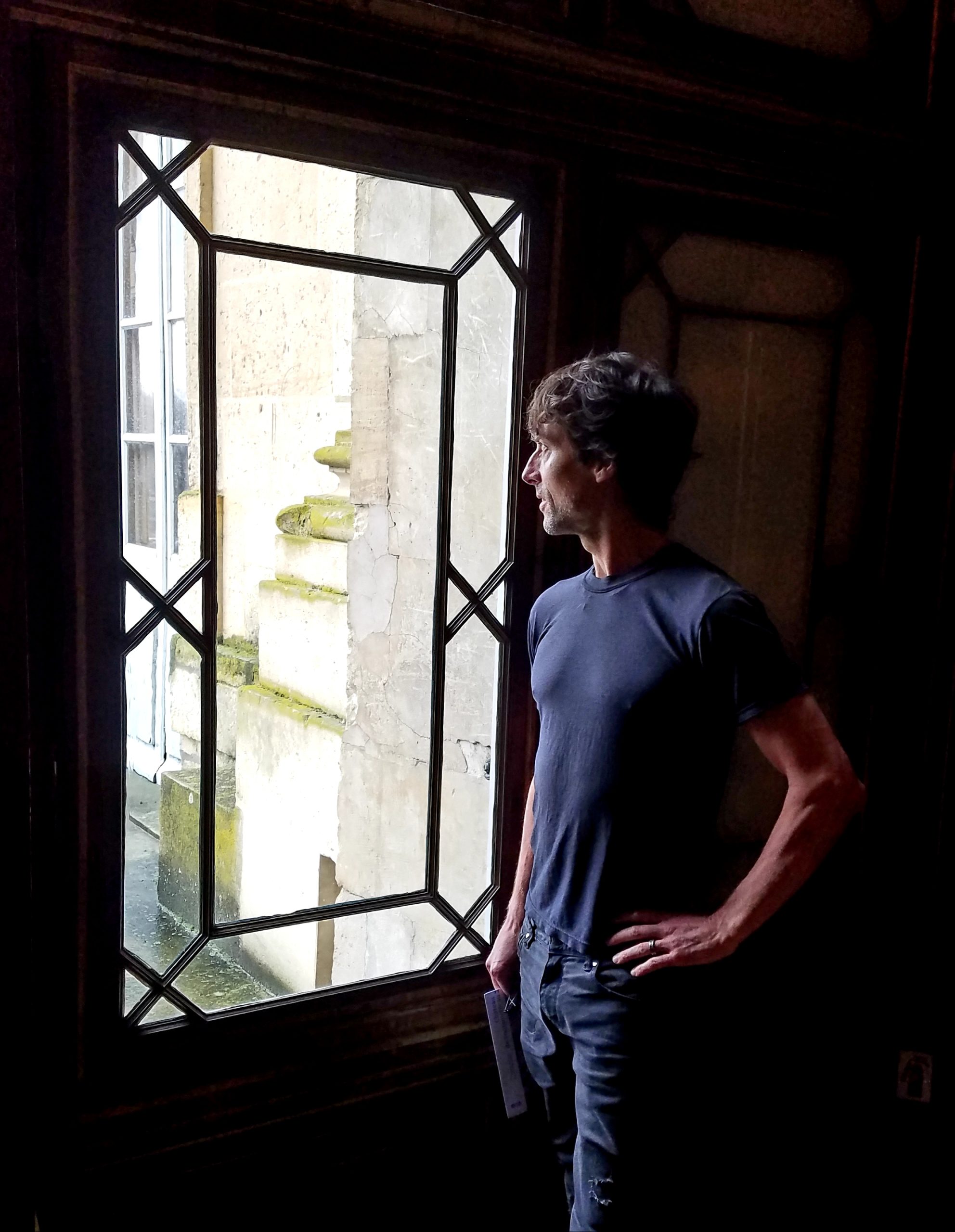

In the afternoons, I would climb the five flights of stairs in our building to the hole-in-the-wall we called “the eyrie.” From there I could look out over the roof tops at the rising immensity of Sacre-Coeur. The slim bell tower foisted among its domes. I could see through gaps in the structure the peak of the great bell hanging in the shade. And the sooty roof of the church that shone iridescent, fog-enshrouded on the clearest day. Down the narrow, winding hall from me, on a small door to what had to be another miniature apartment, hung the jesting, serious sign, “L’Entrée Des Artistes.” Throughout, I was conscious the artist was in there, dozing perhaps, drifting raptly through far-away domains, or gazing out at the cathedral and recomposing what was possible.

My wife’s professor, who was always really kind to us, had offered the key to the eyrie for the last week of our summer. It was an amazing place. She’d rented it while she took French lessons then been afforded the chance to stay in a larger apartment elsewhere in the city. Her brother was coming to Paris for a visit, so now it made sense she move. And having written two scholarly articles within those tight walls in a cramped space of time, she could vouch for its powers as a workspace. On her last night, we all climbed the stairs then took turns at her window, staring upward over the zinc rooves at the illuminated cathedral.

*

While the professor was at her new address and my wife spent a sedulous week at the Bibliotheque Nationale researching her dissertation, I ran the steps up to the cathedral and hung out in the eyrie. But I got no work done on my novel. I could hear the booming of the church bells one hears, it is said, at a distance of five miles on humid summer days. I pictured stone passageways beneath Sacre-Coeur where, in a candlelit enclave, worship of Christ’s heart is ongoing, performed on a schedule of hourly relief around the clock. So somebody is always attendant, worshipping.

From my window, I couldn’t see the tourists choking the entrance to the cathedral. It was difficult to believe they were up there around the walls of the church in a circus of soap bubbles and strollers. All I could hear through the window were the groans of delivery trucks and customers at an Ivorian restaurant and susurrations from sidewalk cafes, making slow time out of smoke or deep murmurs or laughter. Above them were Vietnamese and Algerian and Polish workers pounding on rooves, mending window frames, repairing and rehashing and reinforcing Montmartre which slopes off the hill and hangs over the circles of the city that grow out into the distance, past the river, toward the mirrored towers of La Defense.

More often than not, by mid-afternoon, the great structure of the cathedral became unmoored and began to float above its bustling quartier. The tops of the domes gave up their anchorage. An upwelling occurred, as in a nocturnal sea. Once, I saw the ochreous flare of a monk’s robe shifting from one high portal to the next, the dome itself cut off from earth by clouds. Far below him, swallows rafted through the air. Fog swathed the hillside and buried roof tops, leaving cupulas and the bell tower stranded in the sky. In the thick of that, a brown butterfly floated into view. I tried to work. Yet the monk stayed and stayed. For reasons hidden in our world, he could look over Paris and brush my window with his absent eyes; but though my shutters were swung wide, I was one thing, it seemed, he couldn’t make out.

On another afternoon, a pied swathe of gray and aquamarine bloomed in a portal in the dome. The bells began to ring just at that time, while the colors stayed. Material extended toward an invisible ground. Something akin to solidity started to form. That gaze off traveling. Then the vertical center of the portal trembled—its sleeping ribbon come alive. So distinct from the darkness that had lived there before. Then it faded and was gone. The bells still rang but, unlike other forms, this one didn’t reconstitute at predictable intervals within the bottle-shaped apertures around the dome. It came once, not again.

By the end of the week, I treasured brief moments when there was nothing. No interruptions of the form of the cathedral or infiltrations from within. No fleet presences in the gaps under the dome. No sudden arrivals or stagings of desire. No engulfment by shadows. No dramas of rehearsal. It was such a relief. I tried to capture these instants of concerted stillness in the architecture by looking steadfastly. But they never lasted. If I held my gaze, took things in fully like they took them in up there within the portals, a body would return—low, pale, eyeless moon for a face—and that round structure of dark aporia would be marred. The prospect that it could be over and this circular parade of yearning held within itself an end, that it might not recur senselessly ad infinitum, with new beings materializing, beholding a vast world, then flagging, fading out in their turn, would diminish like a receding form.

It went this way through the stretched length of those long afternoons. It wasn’t tiring. Nor did I dread it exactly. Instead, I looked toward those hours warily as one might foresee a dark fascination one hopes is not self-destructive. By the close of each day, there was just the sun. A scorching ball of fire hung over the cathedral. Profiling the high domes against its light. The church became a world, all in gray-blackness. In two dimensions. The massless power of a great object that heralded something deeper, but for now was just its outline. Later, lit with human lights, there would be another iteration. Visible in familiar ways. Brilliant and desirable. But, at sunset, the cathedral thinned against the sky to a mystery. Composed by subtle architects of memory. By the belief I’d been staring at it all afternoon.

At that late hour, pigeons flew out of the bell tower just before the sound of the bells. They knew everything in advance. They fled their roosts at the behest of visual cues preceding the sound and concealed inside the tower. From the eyrie, I could just make out the glint of mechanics, the growing ecstasy of movement, and detect an initial quiver in the air, a sense of resounding depth through the sonic distance. Then the bells.

The pigeons circled the dome. They floated on mild thermals that rose from motorcycle exhaust toward the empyrean. As light bled out, they scrolled the dusk into a loose parchment hung over an invisible trail. To decipher their fluttering script from so far below, from across such a field of air, to decode it before they alighted within the narrow bell tower and adjusted themselves, folded their wings, would have been akin to remaining in a single portal and beholding the world in the round.

*

“Did you write?” my wife asked when I came down Friday evening, long after sunset. The six o’clock bells had rung hours before. Their waning, the subtle gradations that shifted toward silence once the hour had pealed, were folded into blue darkness. She had come from the library. She’d walked across the city. Now she was standing in our apartment in Montmartre, waiting patiently, generously. With so much beauty.

“No—just looked out.”

But I wanted to tell her how my eyes were still filled with bumblebees who binge in the heights of Paris at balconies freighted with delicate summer flowers that need watering cans—human rain—to make good on the promise of their colors. And with bats I’d seen at dusk, feeding just after the swifts had roosted. Swooping through dusk in their shallow, cut-off arcs. With a harrier who’d spent two wingbeats in the galactic air to cross the dome and soar toward Pigalle. I wanted to say I had the feeling now the figures in that dome were keys to a vast, visual piano. And they were the shortest of notes. How the piano is played through them, with them even, but not by them. How, standing in the heights, they were instruments within an instrument.

So at the possibility they’re bodies, you’re stunned. By the suspicion they have minds, bowled over. Presented with the chance they’ve got eyes—then, just as you desired, all the portals of Sacre-Coeur are empty. For only a moment. But from inside the Entrance of the Artists, you have to imagine, that moment confirms everything.

Wil Weitzel received an MFA from New York University Writers’ Workshop in Paris and his story collection, Nights From This Galaxy, is forthcoming from Sarabande Books. He’s at work on a novel focused on the natural world and cross-species relations. Reading:

Poems by Kevin McGrath

Empress, Shan Sa

Thousand Cranes, Yasunari Kawabata (thx to recommendation by MFA colleague, Jamie Stockton)

Till We Have Built Jerusalem, Alan E. Craven

Photograph by Michelle Weitzel