The three of us: Sean, my brother, holding a cat strangely named Brother, my father, Paul, in a sailor’s cap, kneeling and offering up the fruits of his garden, and me, Regan. Circa 1972. Photo by Ruth Thompson Good.

After our mother died, The Father began to go through his reporting papers and the heaps and hills of family documents kept in a large wooden chest from Mexico, locked with a giant iron lock and key. The chest, part of the spoils from their years abroad, smelled of candle wax and toasted wood. He quickly became overwhelmed by the jumble of hundreds of letters, photographs, manuscripts and other paper ephemera generated by decades of life as a son, student, father, husband, and exceptionally curious man. Now, alone, The Father rummaged through ancient undertaker’s bills, Steeplechase flyers, autographed photographs of bullfighters from Spain and Mexico, newspaper clippings of lightweight boxer Great Uncle Howie Boyd with Joe Lewis, plane tickets, satin baby books and movie ticket stubs. His career as well-respected journalist had produced reams and reams of paper; paper is the debitage of the writer’s life. He’d been Latin Bureau Chief for CBS News in Mexico City, and then Bureau Chief of Atlanta, where he chronicled the major events of the Civil Rights Movement. The Father had known the Rev. King and his entourage well, and when King was assassinated in Memphis, he had been the only white man asked to accompany John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, and Ralph Abernathy to view his body. He’d written a book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, after those reporting years, and never recovered from King’s murder. He wrote two reports for the Commission on Civil Rights, one on race relations in Cairo, Illinois, called Racism at Floodtide, and another, Cycle to Nowhere, examining the intractable systems of both white and black poverty in America. As the nation-at-large boomed, he traveled the South, reporting on infant mortality rates, poisoned drinking wells, and the squalid living conditions inside tarpaper shacks. This reporting turned into the book, The American Serfs, dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., who, The Father wrote in the book’s epigraph, “was killed on the eve of his ultimate campaign to end the American serfdom.” His sorrowful reporting beats exposed the country to the worst blights on its soul, as the trouble he’d seen exacted damage to his own.

The Father pored over school report cards, recital programs, pictures my older brother Sean and I painted and drew as children, birth and death certificates from the 1800s, Xeroxed poems, yearbooks, his dead father’s Social Security card, his mother’s cruller recipe, index cards where charming things we’d said as children had been memorialized. (After my mother explained evolution to me, apparently, I had said, at age seven: “Behind every cell in me is a little ape.”). Bulky packages of these sundry materials were sent via post to Sean, his daughter T. in California, and to me in Brooklyn.

We complained to each other on the phone.

“How many times do I have to read the Blackie-White story?” Sean asked. “The cat died thirty years ago.”

To his credit, The Father once sent me an exquisitely written travelogue from his and my mother’s trip to Malaga in the 1950s; in this single-spaced text typed on onion skin, my journalist father brilliantly describes hideous German tourists on the boat over, the stops at small towns, the meals and the wines, the weather, the town squares, the cathedrals, the sun and sea. He sent T. a scrapbook torn in half that Sean had made as a boy on their freighter to Spain. He sent me a photo of our mother in 1966 and wrote in its white margin, “Terrific girl.” He asks, have I ever read the article he wrote about Raquel Welch? Or the article he wrote about The Leatherman of the upper Hudson Valley, a mute and journeying hermit of a century ago? Or the one about Pavarotti? What about the Life Magazine article about Sean? If not, here was another copy of it.

While the memory-lane packages with their manic scribbled notations irritated me, at least they were not the letters he wrote to me alone over the years. These letters, now filed and sequestered in a single overstuffed blue paper folder, languish in one of my grandfathers’ old foot lockers in our basement storage space in Bedford-Stuyvesant. The Father’s ashes sit close by this folder in a small but mordantly heavy box that had been mailed to me in the U.S. Mail, fresh from the crematorium. The Father’s words—spoken, recorded, written, and sent by the same postal service that delivered his ashes—had formed the matrix in which I grew into myself; one cannot separate the dancer from the dance. These words began to enfold me long before the death of my mother, and their emergence is not assignable to his grief over her loss. The Father and I did not get along. I knew his complaints and admonishments by heart and accepted that my being was indivisible from them; his anger had started before I began to form a self. His inimical words shaped my psyche before I could read. These letters were the written equivalent of when he had been angry at me as a child, and his rage at me had only grown hotter as I had grown up. These were not the words of a fair-minded journalist, but words inked by an unearthly poison, a Poe-like hemlock, as if The Father had accidentally stumbled over a hell-crack in reality where a demon rose up and whispered in his ear that his princess daughter was really a bridge troll born specifically to betray him. Since I had turned thirteen, the Father could not abide that my child’s devotion had changed into skepticism and critique. Incandescent and unsolvable, my father’s rage burned brightly. No wonder, seeing an envelope from him crammed into my lopsided letter box would trigger a wobble in my soul.

#

During the early days, after our mother died, my brother Sean and I created lists that we would return to for the next ten years on the occasions when The Father went missing. We knew to first call The Lemon Tree Lounge, his usual haunt, a dreary cocktail bar on the Fairfield border, then the Westport Police, then the Ombudsman, and then the Norwalk Hospital Emergency Room. We always found him since he was never really missing.

One night, however, now carless, he stayed at home to play out his grief-inspired wanderlust and drank himself into hallucinations. Only the cats know what occurred before my father called the police because, as he told them, there was a circus troupe with monkeys and costumed clowns in full make-up, running amok in our small patch of woods at the end of our lawn. Couldn’t they see them? After the cops left, he called me in Brooklyn, sometime after three-o-clock a.m, eager to explain how he had been sitting in the front room on the second floor as the clowns knocked on the windows, and how they rose above the stone front porch like paper-mâché puppets on sticks or demented helium balloons—smiling and taunting him, sticking out their tongues and wagging their faces. He explained:

“I saw them running across the goddamn lawn, do you understand? For Christ’s sake, Regan! They have their caravans in the woods, too, parked on our property.” He was wild and out of breath.

“Okay, Pop,” I said.

“Okay, Pop? The goddamned clowns were knocking on the goddamned second-floor windows, for Christ’s sake! They were taunting me. There were monkeys with them. They knocked on the windows and, oh God! Then they stuck out their tongues at me! I smacked the window and they disappeared!”

The Father was in a lather: “I got my shotgun and challenged them. But there were too many. I called the police, but when the goddamned cops came, they took my gun away. Can you imagine that? My gun. Those slobs are going to pay for this.”

“Pop, I’ll be up tomorrow,” I said.

“The monkeys are in the woods right now, with the clowns, and what I am trying to get through to you is that they are trying to take this house!”

I called Sean, who had already spoken to him.

“It’s bad this time.”

“Jesus Christ,” Sean said, “He told me he told the police all about my giant green ears and my big red nose.”

We laughed until we cried.

“Oh my God,” I said to wrap things up.

#

That winter, after my Italian landlord banged her broom on the ceiling for the last time, I began to look for a new apartment. Antrim returned from a writing colony and threw his literary weight behind my shaky application for a place further down the Slope. From the living room of the apartment, I could crawl through a window and sit out on the roof of a small adjoining garage. Theoretically, one could sit in the sun, but the black tarmac sucked the sun to it, and the roof roasted and boiled. A batty upstairs neighbor had a habit of throwing wet cat food out her window to feed stray cats who traversed the rooftops, and so I often sat sweating in what felt like a sea of vomit and black flies.

Antrim was a big one for “taking care of the chompers” as he’d say, and that year I had two wisdom teeth pulled in one day in Manhattan on the Upper East Side. I had walked to the subway back to Brooklyn, spitting blood behind trucks and parked cars, chewing on the bloody cotton webbing in my mouth. The term “wet wound” came to mind, and I longed to fill the two gaping pits with whiskey, like a Civil War soldier on the battlefield. I had asked the dentist if I could take the teeth and keep them, and the hygienist had wrapped the two teeth in white gauze and put them in a tiny manila envelope.

The teeth were absolutely fascinating objects; their long yellow roots reminded me of the “fat bodies” of frogs—waxy finger-long yellow branches of fat—revealed during dissection in high-school biology class. I wondered if the roots had been flexible when the teeth had first been pulled because their roots had crossed over, it seemed to me, fused, and then hardened at odd angles. I imagined an extremely tiny drill taking core samples from one of the teeth, removing perfectly round cylinders of dentine and pulp to be analyzed for historical isotopes. One of the teeth had an odd round hole in it, the exact size of a pencil tip. The hole seemed evidence that a shipworm had begun to eat my mortal mouth; in maritime terms, there was no denying that I had the worm.

I made my way to Antrim’s apartment on Carroll Street with a prescription for codeine and my two loose teeth in their Lilliputian envelope. I parked myself on his living room futon and began to babble. For now, there would be no arguments between us. Day after day, he brought me cups of tea and bowls of soup and listened to me chattering on and on about Kurt Cobain—I had been reading Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana by Michael Azerad—as I deliriously spat blood into a mixing bowl and dreamed drug-induced dreams of eating cream cheese and canned crab on crackers with Kurt under a bridge. When Antrim was not looking, I took the teeth out to examine them and rattled them in my fist like Captain Queeg from The Caine Mutiny. I shook them like dice and thought of the ancient game of Roman knucklebones, whose rules no one knows.

When I got back to my apartment, the first thing I did was take down my mother’s giant white sugar bowl from the bookshelf—the same sugar bowl used for the proceeds from all Good Family tag sales. Large and nearly square, yet with Art Deco lines, the heavy-lidded porcelain sugar bowl with its 14K gold-leaf top knob had belonged to my Flatbush grandmother, my mother’s mother, Mae. Grandma Thompson had used it as a proper sugar bowl, not a change purse, but since the bowl had become mine, I had filled it with stray copper pennies. That afternoon, as I lifted the lid and popped the teeth in the bowl, I thought how teeth and money seemed a physical metaphor for something profound: the mortal bits of me mixed up with a bunch of dirty pennies.

#

Something happens around this time that irritates me and Sean quite a bit. We did not detect the date things changed, but gradually it became obvious that Bowie had fixed his teeth. Capitulating to the standards of the Red Carpet, he had allowed for his Brixton teeth to be Americanized: where once had been a beautiful bouquet of yellowed shards, there was now a straight and white piano keyboard. His divine facial structure remained the same, but now a set of ghastly gin-and-tonic teeth shone from between his lips. Bowie changing out his teeth was a sort of Ruth Thompson Good “Paint it white” gesture, yet Bowie’s imperfections had made him perfect to us, and now he had done something to fuck that all up. We discussed this horrible development over the phone, which seemed to be about removing all homely and human texture and detail from the world. His mouth looked like what Westport, if not the entire world, was becoming—sanitized and banal.

“Why did he do that? His teeth weren’t just his, they were ours,” I said. “I am so upset.”

“Blame Iman,” said Sean.

“Well, they were pretty bad teeth.” I allowed. “Maybe they were falling out of his head. Maybe they were worse than ours.”

“Oh my sister. The truth is,” Sean replied, “Bowie’s original teeth must be there somewhere under all that porcelain, so they do still exist.”

I had been comforted by that thought. Bowie’s mouth was a palimpsest, a Dagwood sandwich, a T.S. Eliot-like Time-future-is-Time-past-and-Time-Present poetic truth, a layered, revelatory archeological site. He was the sum total of his history and his choices. I imagined, though, that despite this gleaming new set, he still felt his mouth to be shameful, as a person who loses three hundred pounds continues to think of themselves as obese. That is, if Bowie wasted time feeling shame, the least remunerative of all human emotions.

#

The Father’s teeth and their whereabouts were a preoccupation for him, and so by association and extension, for me and Sean as well. The Father’s mouth became more and more a dark hole, a twisted-lopsided orifice, until he had one front tooth left, and the rest only brown wobbly nubs flush with his gums. Sometimes he woke up in bloodied sheets, his mouth weeping all night. Many phone calls flew back and forth across the nation as my father fretted over his lost teeth.

“I put them right there, and now they’re gone,” he’d say.

“I’ve ripped the house apart!”

“Dad, did you try the garbage?”

“’Dad, did you try the garbage?’,” he’d reply, mockingly, “Now that’s just insulting.”

He looked under the bed, looked in his pant pockets and his shirt pockets; he looked in the driveway, then scanned the ground between driveway and back door, retracing his path, kicking clumps of leaves and sticky balls of pine needles, cursing his teeth, the cats, and the Heavenly Lord.

“Oh for Christ’s sake, Goddamn it!”

Sean might call me in the middle of the night and ask, without saying hello: “The Father wants to know if you know where his teeth are?”

We laughed and laughed.

Paul Good had lived fast and loose with his decaying teeth, always opting for the riskiest dental course offered up by the family dentist, resulting in precarious and often simply unworkable outcomes. These courses of treatment were driven by The Father’s idea of the natural order, which turned out to be wrong. The tenuousness of his teeth was profound; each one had something distinctly wrong with it that required an implanted rod or binding, strapping and stabilizing with a metal band, or the attention of some kind of affixing cement or glue that was not going to stay bonded for long in a wet environment like a mouth. He was forever delicately applying stinking viscous orange pain medicine to throbbing teeth with the ends of Q-tips. Dentures at an early age may have been required, but being as vain as the day is long, he’d held on to every tooth like a sick pet, keeping it alive until the inevitable happened. He’d been in a fraught relationship with the dentist in Fairfield for years, and my mother often sighed when the man’s name was mentioned.

“That man has a new tennis court in his backyard because of this family,” she’d say.

#

The Father became fixated on how what he grandly called “The Estate” would be divided upon his death. He wrote dozens of letters to me and Sean on this subject, letters enumerating each piece of furniture, as well as the numbers of various bank and insurance accounts. He claimed to possess a “Master Document” that would guide us when the time came, though when it was discovered, months later, nailed with house nails to one of the Mexican tables, we better understood the extent of his grief-stricken madness. He’d scrawled various arrows across the single page of typing paper, connecting accounts with asterisks and calculation updates; he’d circled several issues aggressively in wild spirals to underscore important points of loss. Each account’s value had been crossed out and rewritten in various inks as the accounts depleted, so that each account had a raggedy thin column of numbers trailing from it like a receding comet’s tail.

The Father’s monthly Estate assessments came with the unspoken understanding that he was not going to live much longer. Pop would ominously declare he was “closing out” the memorabilia, whatever that meant, and wouldn’t Sean and I like to make lists of what we wanted? As Lear had wanted confirmation of the depth and degree of Cordelia’s love, my father wanted Sean and me to name each family object we desired, as if these inanimate objects represented fealty to our parents’ cosmological regime. To want these objects was to sanction the family in his mind, and to indicate that, yes, this elaborate stage set was worth saving, and that if we could, we’d launch the whole show again without changing a single lampshade.

The thing was, Sean wanted nothing; unlike his sister, he was not a materialist. Sean wanted nothing more than a single Mexican wrought-iron candlestick that was part of a pair; the rest was mine. In robust physical health, my father’ natural death was, in biological theory, decades away, but the unspoken known now was that The Father harbored ideas of joining mom. What they had not achieved together, he would do alone. He raised the specter of his suicide without embarrassment, saying it would be a good thing, a consistent thing to do. Ideas of what he called “loyalty” and “consistency” ruled his thinking about how to live a good life; one was loyal even to a sinking ship, the consistent thing to do was to hold on as it went down. Captains died with the ship, the ship was mother and lover. So, if he said he couldn’t live without mom, well, then he could not live without her.

What is sadder than a dead house, dead because of the death of its mother? The house is The Mother. To visit The Father during these years at the house was excruciating; his unhappiness was so deep, he was often out of breath. Grief turned him into a Dresden firehole of black glass; he was an immolated tube of vitrified sand. I thought of lonely men in shirtsleeves, and did all I could to avoid his pain, which meant keeping him at arm’s length, his worst nightmare. For me to go to that place with him meant I may never come out. I felt that very strongly, that I had to claw forward, into some light I could not exactly imagine, because to enter the vortex of grief of 119 Old Road meant I would be trapped there forever. The house grew filthy and it smelled, as my mother would have said, like “cat dirt.” The poor things grew wilder and more confused as their home also vanished.

As the house devolved, my heart physically hurt the evenings I took the train from the city to Westport, to climb the back-porch stairs and enter the dead house. My father would have tried to make things normal, but there was no normal and I could not smile. I failed him terribly and totally. I’d failed him because I was afraid of his grief. And my grief? Fulfilling my father’s admonishments, my blood had run cold when my mother died and I effectively stopped feeling anything; this was an unusual state for me, being empty in the center. My mother used to tell me to be a woman, which meant to manage with a stiff-upper lip, and I had done that but mostly perhaps, I had retreated internally so that I hovered for years around my own heart like a moth. Now that I was a woman, I would behave like one.

#

I recall a single peaceful day during those awfully anxious years, a single summer weekday I spent in Coney Island playing hooky alone on the beach, a day that spoke of a future I couldn’t know, one of happiness and light. One hot morning, I decided to walk away from the tangled mess I’d made and to try to enjoy a summer day. I had attempted freelance writing with no clips or journalistic training other than being my father’s daughter, and I was broke. None of my pitches had the correct news-peg; I was interested in both everything and nothing. An editor’s simple question, “What’s your angle?” confused and intimidated me. I felt panicky and unable to concentrate on any subject long enough to make sense out of it; each world transaction seemed a complex equation to be solved by numbers I had not been taught.

I put on a bathing suit, packed a bag with a fat joint and a blanket, and took the F train to Coney Island. Off the train, I crossed over seedy Neptune Ave. and walked past the roller-coaster, the Whip and the Fall-Drop, over the boardwalk, to the shipped-in sands.

This particular day, there was no one at the beach but me and a Russian man wearing black Cezanne-style bathing shorts. He did old school calisthenics on the sand, preparing himself for the long swim across the bay: lots of toe-touching, waist-twisting, and arm-waving. I admire the Eastern European health regimen of sweating and freezing; my father always loved a steam room, and his deadman floats incited cacophonous whistle blowing by Compo Beach lifeguards over the years. Saltwater and sun could fix anything, my father believed, just as the English believe a cup of black tea with sugar and milk mends whatever ails you.

The sun shone hot and the sands baked as I sat with my eyes closed, allowing them to melt into my brain and fall back into their sockets like freckled crabs burying themselves backwards in the sand. In Manhattan, people toiled on carpeted floors in cubicles in office buildings; they were not here at the beach like me and this 19th-Century Russian man. Usually the waters were a messy scum of bubbly motor oil and industrial cruds, but, that day, Coney Island’s waters sparkled. Her waves crashed, beckoning. I plunged in to cover myself with the salty waters of the Borough of My Birth. I emerged and stood, dripping with saltwater in the shallow bay, to look back at the sand. I felt weirdly whole and at home there on the spit of sand with the bones of the dying arcade in front of me. Here, Evelyn, my Sheepshead Bay grandmother, once danced in a butterfly costume and rode around on the sand with gangs of spirited boys in large-fendered cars. My father’s mother’s family, the Costigans, had once had a boarding house here that let rooms to the freaks working the Freak Show. How had Margaret Costigan survived the drowning of her son Arthur in these waters? How many fires had Great Grandfather Charles Boyd, the butterfly’s father, put out during his twenty years as a Gravesend Fireman? Hadn’t my mother and father come to Coney Island, to Manhattan Beach, the night they were engaged? Yes, we came from this busy borough with its innocent and lopsided hopes, its alloyed tin trays and costume jewelry, its dignified and dinged dreams.

All of that living was now balled up in me, who stood in the shallow sea wondering what alchemy allowed the dead to beam back from old photographs, sitting under grape vines in backyards or toasting each other at tables set with Sunday roast beefs on bloody platters. With what could be called “pep,” my ancestral Brooklyn families—the Boyds, the Goods, the Thompsons, the Costigans—stumbled along, making it up as they lived. Despite the kooky industry and sometimes sodden alcoholic results, these inhabitants lived, it seemed to me, fully, in a way I could not. Their lives had a camaraderie and cheer mine lacked, and I tried to imagine what it would have been like to be ensconced in busy households and half-baked family businesses, with siblings and aunts and uncles, all pushing forward, through, and finally, out of Brooklyn. My parents had moved the whole show to Westport, and I had driven the bloodline right back to Brooklyn for it to die.

Yet, that day I had done the impossible: I had lived like my motley ancestors. I had lived as if I were not doomed. I baked myself, turning my towel to keep the sun in view as if I was a sunflower head. I watched the Russian wade into the water and launch off with an explosion of wicked, choppy crawl strokes. He moved like a mechanical doll across the water. I watched him churn away, and then I gathered my things and walked down the beach. Eventually, I cut left up onto the bustling Brighton Beach boardwalk, where the Russians rule, where one can be served fresh borscht while taking in the view of the bay. I reached the streets under the elevated train where the Russian shops sell candies and caviar. I bought a Matryoshka, a painted wooden nesting doll—the doll inside a doll inside a doll inside a doll. She was exactly the same in every iteration. One opened her, pulling head half away from lower half, pair after pair until the revelation of the tiny, perfectly indivisible doll at the center of the shells. If one tossed the Matryoshka into a fire, this hard doll, this nugget of wood, might survive, scorched but intact—as a solid cinder. I thought of her as the kernel doll, the atom doll. I climbed back onto the F train, sun-burned and salty, holding my doll, the smallest one rattling in there like a hard nut surrounded by folksy and gaudily painted husks.

#

Evening swinging at 119 Old Road after a day at the beach in the early Seventies. Paul Good and Regan Good. Photo by Ruth Thompson Good.

The Father made no distinctions between psyches or developmental ages; a child could betray him just as thoroughly as an adult, and so a child received the same treatment as a man. From four to five years old onward, if The Father was displeased with me, he would lock his cornflower blue eyes to mine and say, “I know what you are,” menacingly, or “I’ll remember that,” indicating eternal displeasure, confusing concepts for a child already scared that the Klan might be approaching on horseback. As I grew older, if he was not speaking to me, he might also press himself up against a wall if I passed by him in the hallways of the house. No wonder I sometimes slipped those freshly received letters and manila envelopes into drawers, unopened. The emotional power of The Father’s packages could have flattened Tokyo.

The letters offer a psychological profile of the man and reveal the wild swings of his tormented inner pendulum. People assure me that no father should write such letters to a daughter. I will burn them all one day, when I have a yard with space to burn things: their vanquishing requires a fire ritual. Until then, I keep them, thinking I might this year be able to read them without being tossed back in time to fight the original fight. Not possible; I can only shuffle through the pages to this day, high as a kite, reading with one eye closed. My husband has read them all, and cleverly devised a system of colored Post-it Notes to indicate passages he finds “lucrative,” in a psychological sense. He understands me better after experiencing The Father’s prose’s particular pitch. These written messages do not define Paul Good, but they do reveal the integument of his mind. His brain was one thing; his mind was another.

Some of his billets never touched the US Mail. One, for example, was left for me on the kitchen counter after I had spent an afternoon with an old friend in Westport, instead of lugubriously sitting with The Father in our dead house counting our losses. As I pulled into the driveway returning from this brief walk on Compo beach, I saw that he had loaded my things on the side of the driveway. On the kitchen counter, on the back flyer for plumbing services, he’d scrawled this note: “You dirty little dog.”

His jeremiads about my sinfulness were imaginative and descriptive: he especially liked to say that I was “unnatural,” “disloyal,” and that I had “ice water for blood.” The Father’s letters are vituperative, bathetic, over-the-top slogs; for an intelligent man, he let himself engage in deeply purple prose while castigating me for slights that sometimes had never occurred. For example, one letter outlined at length his mortification, grief, and embarrassment when, at my wedding that not long after ended in divorce, I had haughtily and publicly refused to dance with him in front of all of our assembled wedding guests. That was cruel! But the truth was there had been no dancing at the wedding at all—no dance floor, no band. There had been no traditional father-daughter dance to refuse. Similarly, if he sent me $300.00 one month, the next month an angry letter would claim it had been $13,000. If I spoke to him one week, in a letter the next week he’d claim I had not called him for months. Many of the angry letters had been sent Two-Day Air so that I would get them while his anger was fresh and white hot. These letters were signed, curtly, Paul.

Old arguments like familial sine waves flowed through each missive. His favorite refrain was that I had become “a killer of family dreams.”

I thought you must be proud to have a strong father who spent much of his adult life writing and striving to make society better, not just aimlessly making dough like so many of your friend’s fathers you pretended to scorn but secretly, I think, envied for what they could deliver. Could there be a whiff of a Westport girl in your material values, your friends, your attitudes in the house, taking but rarely giving back, increasingly quick to judge others but slow to judge your own faults….

Only later in life did I try to imagine what life would have been like with more fiscally responsible and monetarily talented parents. I could not imagine growing up without our money anxiety; my imagination simply failed me. My God, we were who we were–! And, of course, I had loved him, but his obsession with me frightened me until I felt a kind of internal psychological melting under his gaze; I would go down with his ship if I remained onboard. He drew me to him through guilt and admonishments, through anger and castigations, and then wondered why I stayed away.

Day after day I score you to the point of obsession for denying me the opportunity to act like, to be the loving father that I once was, for reducing me to this Lear-like character, a role I used to joke about to new acquaintances when explaining your name, a joke that now has become maddeningly true.

But it is this verbal message, left on my answering machine one evening after an aborted day trip to Westport because of his drunkenness, that was his most economical, Lear-like dressing down of his Cordelia. He’d laid into his slurred words and spat them at the phone as my recorder recorded them, and then he had slammed the phone down.

I hate you. I hate you for what you’ve done. You dirty little bitch. You ruined today just like you’ve ruined most of my life. I hope someone abandons you like you’ve abandoned me. I hope you die, I hope you die hard. I hope you suffer.

I believe his message to be to roughly iambic, with interestingly reversed feet inserted for meaningful effect; I can hear it still, decades after I first listened to it in my apartment with the cat-food rooftop on 10th Street.

All of his angry letters and verbal attacks fall away, however, when I think of a short note he sent me from the grave. One afternoon, years after his death, as I sorted through family photographs, I came across this note which blots out all the ugly mailings like an elemental sun. I’d found a photo of him pushing me on a rope swing. In the photo, I am wearing a white nightgown and my recollection is that this picture was taken after a day at the beach. It is evening because the sun is at an evening angle and I am freshly bathed; my blond hair combed into a side part, my light nightgown full of sun. My father is shirtless, in white swimming trunks, as he called them, and he stands with his arms outstretched, pushing me away from him. The sun is making everything fuzzy and golden and the ’70s are in—no Paul Good pun here—full swing. As I held the photo up to the window to see better, as I held it up into that sun shaft floaty with dust moats, I saw black ink on the back. I turned the photograph over to find that he had written, in a shaky hand: “I didn’t know how good it all was.”

#

After one Westport weekend, I arrived early for the train back to Grand Central, and instead of freezing on the platform, I walked to a ratty old Westport hangout called, of all things in this town of sailboats and golf greens, Viva Zapata.

The restaurant’s many rooms were lined with bookshelves which held the kind of books found in a summer house or at the end of a library book sale: swollen paperbacks, novels from all eras, but especially the ’70s, cookbooks, broken sets of encyclopedias, business biographies, and sports medicine books. As if ordained, the first book I pulled from the shelf was a 1965 Time-Life book on animal behavior full of fascinating, and heartbreaking, information on animal instinct and the emotional lives of our sentient comrades. My eye first landed on a black-and-white picture of inchworms slavishly ringing the lip of a teacup. The caption reads: “Trapped by their rigid instinct to follow each other on branches, caterpillars trudge endlessly around the rim of a cup.” The text goes on to explain that the inchworms will follow each other around this rim to Nowhere until all perish, being bereft of what can only be identified as Free Will or independent thinking. They follow the leader to death.

There are photographs of the famous experiment using monkey babies being introduced to Faustian “wire mothers.” One wire mother, really just a roll of chicken wire without a head, is outfitted with a bottle of milk; the other wire mother is covered in soft, wooly fabric. A desperate monkey baby will choose the cloth over the bottle, proving babies will choose warmth and comfort over sustenance. The same deprived monkey, unable to play normally with other monkeys its own age because of experiencing such terrible choices, is shown cowering in fear as another monkey slaps it on the head.

There’s also picture of a big fat white hen mothering two orphaned kittens under her wings. And another is of a bird altruistically feeding an open-mouthed goldfish a beak full of dirty worms. Also, a lovely man, resembling Santa Claus, swims placidly with two adult swans he had raised since the goslings had pecked their way out of their respective swan eggs.

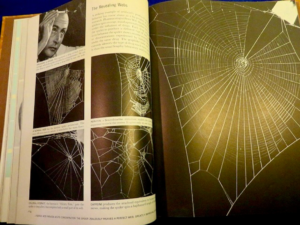

But it is an experiment paid for by NASA, conducted in the late ’60s by pharmacologist Peter Witt, that resonated with me the most regarding the lives of the remaining Goods. Using drug-soaked flies to administer chemical agents to the spiders, the good doctor fed his subjects various pharmaceuticals: Pervitin, chloral hydrate, caffeine, and lysergic acid and sat back and simply recorded the results. The accompanying text described the webs woven under the influence of each drug: design errors and lack of fortitude were rampant. It was hard to call the resulting artifacts webs at all. A sober spider’s web is a brilliant thing, even if it is naturally flawed; a seeming symmetrical masterpiece marred by the occasional dropped stitch. Like the Navajo weavers who deliberately seeded errors into their weaving so as not to compete with God’s perfection, even the spiders agree there is no perfection found on earth so why bother trying.

The drugged spiders failed to spin their webs in various ways. The spider on Pervitin, a methamphetamine stimulant, made the spider impatient; he spun a small circle of the web in the center, and then made a few short woozy passes back and forth, completing just one pie-shaped segment before giving up. The spider slipped chloral hydrate, a “Mickey Finn,” made an attempt to lay out the basic underpinning of his web, but then quickly fell asleep. The spider on marijuana made a reasonable stab at his net at the outset but then quits halfway, either distracted, sleepy, or simply content to daydream a vision of a web rather than produce one. The spider on caffeine spun a drafty, loose mess, a disconnected web that could only catch the largest and lightest of flies—or dry leaves or milkweed spores. It had no center; its filaments connected to each other in long, impulsive strikes.

The spider on lysergic acid (LSD) spins a brilliant, rigid, perfect web, one “greatly improving on nature,” according to the caption. Indeed, the web shines in its radial perfection, verily looking like a map of the mind of God.

Tinbergen, Niko. Animal behavior, (Life nature library). New York: Time, Inc. 1965. 10.8” x 8.5” x 0.6

What kind of web would a spider weave on alcohol or heroin, I wondered? If my father had been a spider under the influence, he might have woven a handsome web of endless tangles. He may have gotten the basic underpinning strands down, those that anchor the web to its worldly corners, but the result would have looked like a madman had knitted the web wearing baseball mitts. Sean’s web would also have been eccentrically spun; it would have been very beautiful like him, though half-finished, as was his life. Both webs would have sections of gorgeous, tightly woven threads, and both would have been shot through with duende. In dew, they’d read as glittering lawn hammocks or crazy blueprints for random star charts. Their webs would have been humble, homely, human webs.

And my web? I might get points for simply knowing how to weave at all, considering our peripatetic family and its difficult ways. I often thought, as I sat in my cat box of an apartment on 6th Avenue during those years after my mother died, that the three of us were like three spiders hanging in our own solitary webs. Without our mother, without a wife, we had retreated to the far corners of our solitary, slack, and ragged worlds. Little death shrouds surrounded us; we wove them ourselves. Alone, each of us ate our own doused flies, so to speak, and so stoned or drunk, we spun our impaired webs without enthusiasm as we wasted time. We flagrantly and hatefully wasted time to make it pass quickly. Blunting our brains, we sat in front of our televisions, the tube’s dulcet tones killing the thoughts and feelings that surprised each of us daily with their consistency and depth. We sank from the loss and our regrets.

When no one was looking, I slipped the book in my bag and walked to the station in time for my train.