Listen to Sarah Minor read "The Listening Rooms."

69. The Meaning of Night

From her front porch, the woman sees a man walking towards her with an exceptionally tall head. He is wearing a backpack and moving along the sidewalk with a head that is five times the height of a human skull. The woman is certain he is not wearing a hat. His head seems light on his shoulders, easy to turn side to side, and just as wide as any face would be if it were stretched as tall as a baseball bat. The man is real. She can just make out the point of his regular nose balanced three feet above his neck. As usual, she tries to focus on the image, on the ticking in her heart, the fear—the hope—that she is witnessing something terrifying before depth and time can tender it. The light is too fast, as usual, and as the man crosses the mouth of the alleyway, the woman watches his real head dislocate from a shadow the street’s up-lighting had made on the far wall as he passed. A small relief and a greater disappointment. The woman, she has been seeking illusions since before she could speak. They remain her only notion of a time before language. Since then, peer-reviewed studies have found that children who pursue visual illusions are more likely to develop addictions later in life, though her own living has not yet corroborated such research. From her rear-facing infant seat the woman once saw the roadside sucked sideways into the window’s beveled frame. She understood then that a window eating the horizon was designed to entertain her, to keep her quiet, as everything continuous was in those days. Years later, in the passenger seat with her temple resting on the plastic window sleeve and her chin against the child lock, the girl discovered the angle again. She watched the ribbon of asphalt unfurl against her, reeling from the soft corner like a treadmill, as if the car’s engine loosed the roadway for all the machines that followed them like a crusade. Again, there was the feeling of racing downhill, the sense of floating alongside her body, this time with her neck kinked hard toward the glass. “Stop that,” the girl’s mother said, “What are you doing?” She also knew there were many ways to see out a window.

123. The Submissive Reader

The title is the wall upon which hangs the placard. The title wears a prominent hat. The title surrounds the orifice, the velvet tongue extended. Every title contains just one invisible ellipses. The title is a collar. The title acts as underline. In every title there is listed one word none of the characters in the book recognize. The title is a lighthouse undressing you with its eye. And in the technology of the book, a durational form that folds, the title arrives between pauses—in some books, in every upper margin—a rhythmic parallel, beam-repeating. Books are books whether they are closed or open, but not so for essays. When the book closes, the essay is disinvented. The essay will not exist again until its gaze is met.

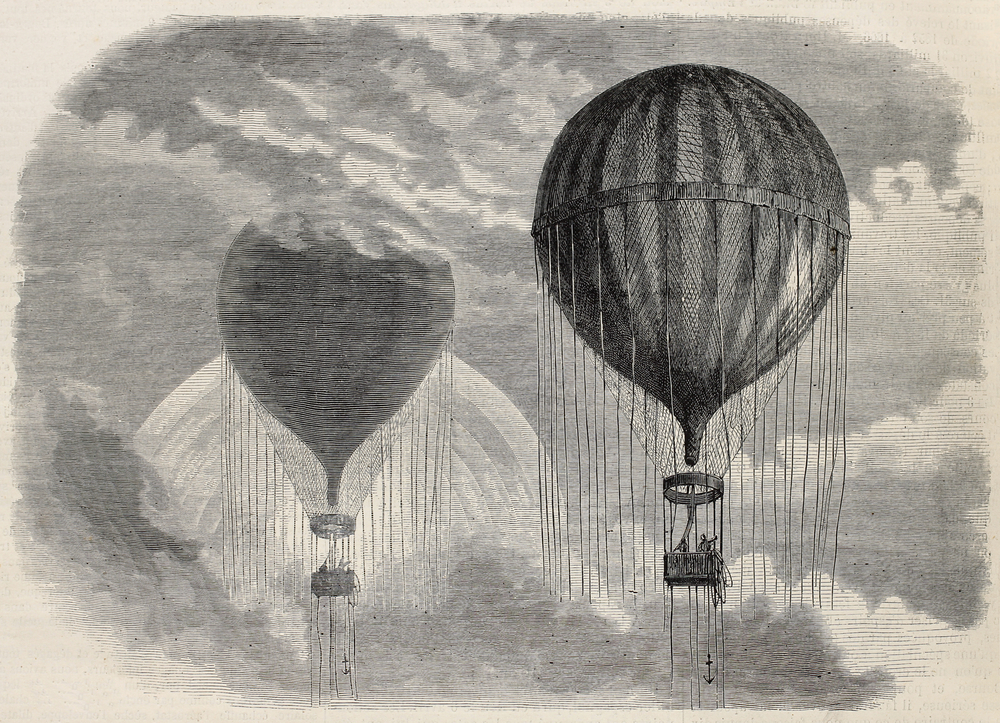

40. The Tomb of Wrestlers

In a July 1865 letter to the editor of the Ulster Observer, John Henry Ronge recounted being dragged, pummeled, and tossed continuously “like peas in a child’s rattle” in the basket of a runaway balloon named “Research.” It was nearing afternoon on July 3rd when Ronge had found himself alone in the balloon after being trampled by his fellow passengers who had ignored the aeronaut Henry Coxwell’s instructions during their landing, ripped the valve-cord off the envelope in panic, and jumped from the balloon’s car. The rapid change in weight left Ronge sailing alone at “house-height” across the countryside, dragging behind him a grappling hook at the end of a forty-foot line. The drawn anchor exploded tree limbs and tossed boulders about “like feathers” as Ronge, moving at 15 miles an hour, called out to passing farmers, begging them to tie him down as the balloon approached the sea. “For god’s sake,” he cried, “help me or I shall be lost! secure the anchor!” Some ran from fear at the sight of the silk balloon, one man fell flat on his face in terror, and several groups of men tried to tie the basket to nearby trees, but the balloon escaped them or tore itself loose each time, eventually rending the rope from the car. The “Research” scraped chimneys from the roofs of farmhouses, toppled stone fences, and bludgeoned Ronge against the side of a mountain before he flung himself overboard into a Hawthorne hedge and survived. Two days later, the “Research” was discovered on the Scottish shoreline containing a copy of Northern Whig, four top coats, and two hats, filled with sand. A decade later, an ocean away, The Times was reporting on “a great year for finding things,” including the skeletons of aeronauts found “bleached, after being exposed to the elements” within the baskets of escaped balloons in Africa, Iceland, and Newaygo County, Michigan.

33. The Double Secret

A canvas on an easel stands before the open window. It is Magritte’s The Promenades of Euclid (1955), a painting of a painting of a city view. The window’s curtains are a deep prune. Outside the window, behind a high line of cumulus, the sky is Magritte’s luminous Maya blue. Paris below is partially obscured by the canvas standing on the easel, blocking the window. Magritte’s first illusion applies the disappearing act every drawing student knows. Painted on the canvas in front of the window is a pointed tower. Painted in the view outside the window is a French boulevard pulling skyward until it snaps like a band at the horizon. Side by side in Magritte’s composition, the narrowing boulevard and the tower become twin, gray cones—a visual rhyme to remind us that depth is a feeling he has conjured. The second illusion is one of vantage: Does the tower’s reference stand just outside the window, past the canvas? If the viewer of the painting inside the painting cocked their head sharply, or took one step to the right, the trick would be ruined. As for us, we feel a tug to step into Magritte’s frame, then sideways. Stuck as we are, there is the third illusion of time: When are we looking? With sore heels pressing on the gallery floor, our temples cooling against the subway pole, the smalls of our back cupped by a lumbar pillow, we stare across humidity-controlled air, across screens, across glass, into a painting, into the past (1955?), where we can just make out two figures standing in Magritte’s boulevard. The tenant of the painted room is maybe a people watcher too. Does he look at the canvas blocking the window as a porthole into the past, where a tower stood (La Belle Epoque)? A time before the war, before the war before that, before Parisian towers fell to and then became pavement (a nostalgic gaze)? Or maybe this vantage is entirely imagined. Magritte’s interior-exterior; an exercise in prospect. He famously insisted that his works were “about nothing.” Or perhaps his deft negation in the years between the wars was a reminder that time’s passage is only as real as the equations for illusion. No matter. Our eyes travel from the vanishing point to the painted canvas and back, shuffling to seek a better vantage. By trying to escape the artist’s tricks, the viewer completes the work of fixing them.

1. The Treachery of Images

On the Instagram account run by Elliee Sharpp, an internationally recognized, 15-year-old photographer, an image of an apple facing a round mirror has 566,861 Likes. Reflected in the mirror is the unmarred face of the apple. On the opposite side, facing the viewer, the fruit bears two bite marks, perhaps made by Sharpp’s teeth. Digitally imposed on the round mirror is the phrase “Online isn’t real.” Sharpp’s apple is rose-red. In paintings like The Listening Room, Jeu de Mourre, and Ceci n’est pas une pomme, Magritte’s tea-green apples troubled the line between sign and signifier to prompt the audience to consider proof of gravity, fruit of knowledge, veracity, perception, and the illusion of objective reality, though particularly the objective reality asserted by technologies for producing “realistic” images, as Sharpp does in her digital context. The white apple of Apple Inc. is a reference from the album art for Abbey Road, featuring a “Granny Smith” apple, which was in turn a reference to Magritte’s icon and his brand of surrealism. In 2007 Apple Inc. won a 23-year battle with Apple Corps. (owned by The Beatles) over the image, stripping Apple Records of its right to the icon, a reference to a reference to a reference. Below “Online Isn’t Real,” Sharpp has added hashtags like #bodypositivity, #conceptphotography and #stilllife. But Sharpp’s is not just the latest iteration in dividing sign from signifier using an apple. Sharpp’s red fruit is not only the apple’s image dislocated from the apple you could hold in your hand. Not just a comment on the limits of photography and photo-editing as shape and light hide bite marks from a mirror’s gaze. Sharpp’s apple has two shoulders, a petulant droop. It stands in for a version of the self that is separate from the self of a new generation that that lives online through depiction. The apple is the teenage self, as conceived by the self, as defined through the multiple digital gaze—a fourth referent. Both Sharpp and Magritte’s work is about perception, and they both like to depict figures wearing hats. Magritte’s mother was a Milliner, a maker of hats, which may account for his second-most famous icon, the bowler atop a figure facing away from the audience, or with an apple blocking his face, a stance Sharpp’s apple assumes by half.

86. Hunters at the Edge of Night

The old woman carries a soft hammer and walks beside a black dog. She carries a very long, light cane to reach the second story walls. She carries a rubber tube passed down from her mother who also shared her name, and a pocket filled with one hundred peas because she can’t afford to miss. On the other end of night, at the turn of the century, the city “watch” looked not out of but into windows in the small hours. When London first began churning according to the clock, still decades before a factory worker could afford a watch, the “knocker-uppers” walked the dirty cobbles, tapping glass panes to wake people who started work before the sun pierced London’s fog, the industrial fumifugium, yellowgreen, made murkier by the jobs they performed upon waking. In this century work begins not according to light but to the tireless tread of machine rooms where hundreds of people work the automated belt below the steam release at all hours. In the next, some residents of East London will still complain about the ghostly tapping of Mary Ann Smith, whose dried peas still rap lightly on their windows a hundred years after tenants paid her by the week to ensure they got to work on time. The penalty for lateness was firing, was empty hands on payday, homelessness, then destitution. So Mary was accurate, persistent with the hard seeds she breathed through her family shooter. She had birthed 16 children. She had worked the assembly line. Like other poor “grannies” who worked as a living timepiece, Mary had aged out of her years hauling stones and shifting clay and turned to more dangerous work. In her pocket she carried a small blade through the streets of the Ripper, to ward off any who might come for Granny Smith’s good watch.

12. The Empire of Light, I

It’s mid-morning when the starlings of Victoria Park rise to flash underwings against a clear sky, July 11th, 1864, a perfect day for flight. Today the birds’ familiar shape scatters above a crowd already murmuring. In Leicester, 50,000 people stand on the green racecourse where a century from now Rommel’s Asparagus, wooden anti-parachute poles, will be planted to impale Germans who fall from the sky. But no one here today has seen a plane, or the air full of men dragging sails, or even their own landscape from a height not fashioned by a painter. This crowd has come for proximity to such vantage, to see Henry Coxwell ascend in his balloon. Coxwell, a dentist, is standing in a makeshift wooden shelter at the center of the crowd, preparing the “Britannica” for flight. The balloon is made of silk, stitched and coated by Coxwell himself. The basket is deep. The audience cannot see him. They do not know the pale envelope remains folded, the careful process of filling gas not yet begun. The crowd presses towards Coxwell, bracing their feet against a racecourse famous for its tight bends, where thoroughbreds bleed softly from the lungs and then the mouth, the only public space where those who own sport horses and those who bet on them lay eyes. Among the stamping crowd there are hosiery workers who arrived on trains from Yorkshire and Nottingham, drunk and wearing bowler hats, as they do on racing days; there are mill workers in horseshoe bonnets; constables in tall hats; gentlemen sporting gamblers; ladies in riding hats braided with horsehair; field workers who have driven from the hamlets in straw bowlers; and among them are quiet Chartists who wear knobs on their bones from the riots of the past decade in a city where the working-class has fought bitterly to get in on the vote and out of the workhouse and each year has been denied. Today they have come for Leicester’s right to witness. The crowd rocks against the shelter holding space for the balloon to expand. The men in the center pound the wooden planks and the constables bang back. It’s no wonder that when a rumor passes through the audience, from chins to shoulders—“A constable hit a woman”—that it comes with the news that “this is not Coxwell’s largest balloon, nor his newest,” the one they came all this way to see. The planks holding space for the shroud break under the pressure of hands. A group shimmies past the barrier and the others tear the structure to the ground, dispersing the constables, exposing Coxwell and the waiting shroud.

60. A Taste of the Invisible

In an online discussion, someone has mistaken the question “why can’t you wear a watch?” for the question “why don’t you wear a watch?” and replied with the comment: “phone tells time.” A moderator has posted the follow-up question: “what did you use before the phone?” and the commenter has replied: “my mom’s phone.” For many decades, wearing a wristwatch with a Tuxedo was considered gauche and associated with bad luck. There was the aesthetic problem: the wristwatch knocking cufflinks, the wristwatch bulging beneath a long, formal shirtsleeve. But there was also a temporal gesture behind leaving the watch at home. A watchless arm communicates formal presence: Whatever is happening elsewhere will wait for what is happening here. In a tuxedo, a man is where he wants to be. But Susan can’t wear a watch with anything. Every watch she has owned died in a matter of weeks. She has tried taking her watch off in the evenings. She has tried wearing very expensive watches. She has observed the watch on her arm ticking backwards, set it down on the dresser, and then watched as it began to work normally again. Like her mother before her, Susan’s wrist refuses to keep time. When Susan’s daughter joined the army at 18 and was punished for wearing the inexact time, she successfully rotated a set of five watches on her arm, labeled by weekday. Bobbi and her daughter Josie have the same issue. Ann’s great grandmother, the daughter of a watch- maker, was not allowed in her father’s shop. Brandy says she inherited the problem from her mother, who solved it by wearing a piece of duct tape on the back of her watch where the metal rested against her skin. These women kill time. The most common theory has to do with the body’s natural electromagnetism—atoms and neurons, heart cells and static. Scientists have argued, repeatedly, that it is impossible for a human body to interrupt a watch: not with the composition of sweat, not with magnetism, not with pheromones or pulse rates. The magnetic field strong enough to stop a watch would carry a voltage that no human could survive. But when Josie opened her stopped watch, only two weeks old, it was green inside, as if the battery had corroded. Her mother, Bobbi, had to change her position at the hospital because lab machines quit working whenever she was nearby. Under “Hereditary Problems,” the website “Pickedwatch.com,” an expert guide to choosing watches, explains simply, “Some people have family members who do not work well with these products.”

29. This is Not an Apple

The digits are slippery, like a cast of ill-defined characters. One is a lot like Nine. The woman, she pretended to read hand clocks for years after leaving a primary school with digital monitors above every doorway. In high school she started to read time slowly, counting on the fingers in her pocket, hardest on clock faces with pricks where the digits should be. At 25, the woman learned the word Dyscalculia, like the name of a vampire. The silence between visual sign and numerical symbol. Why she could memorize phone numbers but couldn’t read them aloud without mistakes, why division was easier than subtraction, why the second hand ushered away long moments, why One was a lot like Nine. For years the woman’s mother had set her daughter’s bedside clock half an hour ahead. She called her daughter’s temporal reality “ISL,” swapping “R” of “real” (“in real life”) for the icy first initial of the woman’s name. What time, ISL? Her mother asked if the family planned an outing. But it wasn’t that the woman was reliably late or that she didn’t wear a watch. It was that instead of 6, she sometimes typed “G.” It was that she looked at the clock and felt surprise every time.

117. Perpetual Motion

In La Durée Poignardé, commissioned by the collector Edward James, Magritte painted a large marble fireplace below a gold-framed mirror. The Great Depression has arrived in Paris. The black clock on the painted mantle reads 12:43. The floors are wood, the walls are wainscotted, the candlesticks stand empty, and the black locomotive steaming through the firebox is doll-sized. Magritte has made a railway tunnel of the old fireplace vent, and in place of the coal stove has painted a small, weightless “Black 5” engine driving hard into the dining room. The painting’s title was widely translated into English as Time Transfixed, which greatly displeased Magritte. The French “durée” can reference time, generally, as in dans la durée (“over time”), or it can describe a temporal limit as in durée de vie la batterie (“amount of battery life”), while the verb “poignarder” means only, specifically, “to stab with a dagger.” Stabbing is a physical mode of betrayal, and also a figurative description of pain (“she speaks poignards, and every word stabs…”). After appearing commonly in French documents early in the 18th century, “poignarder” peaked in 1730 and then fell sharply out of use. The aural force of the verb hints at the shock of a hidden blade, as in “poignarder dans le dos” (to stab in the back), while harboring the sense of intimate presence a carnassial verb like “transfixed” delivers. A dagger is not just a knife (“couteau”), but a weapon kept close to the body, a “hand blade” twisted by the wrist—a little crude, a little dull. The dagger is a bridge that briefly connects the body in vengeance to the body in pain (“poignant”). Recently, some have suggested as a revised translation of the painting’s title, “Ongoing Time Stabbed by a Dagger,” but this version strays from Magritte’s conventions—five or six syllables, three or four words (A Blade in Time?). It’s not often that an image is present to coax the right verb from a text, though there is also the complicated relation of Magritte’s titles and his images, often non-sequiturs, describing a second image. But in La Durée Poignardé, the artist is direct. The double accents emphasize likeness with end-rhyme. The locomotive moves horizontally, like a dagger. It jabs with intention, it plunges from the mountainside, penetrating the still air (The Second Hand, Pinned?). The dining room is time itself, but time as a place, “stabbed,” still might not be halted, might still proceed with a dagger in its side, as “ongoing” suggests (Time’s Ribbon, Shivved?).

54. Popular Panorama

A horse is mostly lungs. A horse is a bellows on legs. A horse can be re-made by the machines it once inspired. In the chariot race during the 1899 play Ben-Hur, live horses galloped full-pelt towards the audience, going nowhere. The horses ran on rubber treadmills while steel rails revolved a massive, scrolled backdrop that moved in the opposite direction to create the illusion of a high-speed chase, a theatre of war, though the danger would become real for onlookers if the treadmills ever quit. In 1829, a gray horse outran a real locomotive when the engine failed, and then never won again. In 1878, Eadweard Muybridge shot a man aboard a train and then lost a bet by stopping time at a racecourse in Palo Alto California. Muybridge designed a zoopraxiscope that could capture images of animals that the human eye couldn’t see by attaching shutters to trip wires triggered by a galloping horse, “the source of all locomotion of importance.” The resulting images rendered the horse and jockey galloping left to right on a small round disk that played on a loop. In “The Story of Painting,” sister Wendy Beckett’s series that introduced Art History on public television, she describes the Caves of Lascaux, a long and winding cave system with walls covered in images of animals--deer, horses, and aurochs, the ancient bison, from one end of the cave to the next. In her first episode, “The Mists of Time,” Sister Wendy walks us through her favorite image in the cave, a drawing of a horse. “The Mongolian horse doesn’t really look like that,” she says, “with the great sway of the belly and the sharp nose, and the inspired black calligraphy of the legs. It’s, dare I say it, an impressionistic horse. An impression of a horse. And yet, an awed impression. Almost as if the artist wasn’t trying to show what a horse was like but what it felt to be a horse.”

6. The False Mirror

A title offers two frameworks; a context and a counterweight. Order is key: Does the viewer read the title before, after, or while looking at a painting? Like the initial entry in a grocery list, the rule of text is that the title comes first, suggesting a lens, an origin, the root of “aboutness.” To disrupt this a professor in grad school advised me to always use or two-word titles for a piece of writing driven by association, and to add winding, dissonant titles to a piece of writing driven by story. But it is usually impossible to read the title before you see a painting. Imagine how large the font would need to be to catch our gaze in a gallery first. Despite the primacy of scale, “Untitled 1” and “Untitled 6” are popular styles in a post-postmodern era when painters are taught to facilitate “raw” audience reactions, or “cold reads,” unmediated by text. This mode is a version of counterweight titling that suggests the title can negate itself. And I have always felt that “Untitled” is heavy-handed, is a loud “nothing.” Because the ethos of a pure art experience of course extends to the white gallery walls, the space between canvasses, the entrance fee, the backless bench, the din of the museum’s HVAC. In poetry a title can serve as the last line of the poem without actually landing there, because the process of reading might make us forget the title, and because the eye often travels back to the top of a short poem at the end. This seems true of the process of looking at painting, which is arranged to allow a title to ring again and again.

11. Man in a Bowler Hat

The woman, she is running on a treadmill, watching the new art museum go up from the third floor of the Wellness Center. Attached to the treadmill is a 2x3 foot screen that cannot be turned off. As the screen counts the minutes, it rolls footage of trails and walking paths under the italicized brand name. The footage is taken by a camera attached to a bike that once followed a trail through a rainforest, pedaled the streets of Luxembourg, then Manila, then traced a path through Iceland’s volcanic rubble. The woman can’t remember the footage ever switching locations. Does it fade from one place to the next? Does it cut to black? Sometimes she feels a twinge in her knee. Then it is Germany, Seattle, Switzerland all over again, on a loop so short that she has come to know the bystanders who were there when the camera pedaled by. On an unnamed beach a father shuffles his toddler out of the way, then glares. In Tampa, a runner waves his palm close to the lens. The woman is comforted by the couple looking back in surprise just before the camera passes in Iceland, leaving them to their hiking snacks and oblivion. Mostly, the woman doesn’t watch the footage. The art museum goes up slowly, black brick by plate glass by concrete stairs. Her friend who works there has told the woman that inside they are building a light well, a pillar of glass where snow can fall and rays can diffuse, but never strike the art. Behind the woman, behind the gym, a factory steam release points at the sun, and all day and night furrowed shadows lap at the museum’s northern wall. Beyond that wall is a windowless, temperature-controlled room that can drop below zero if her friend pushes a button and where curators recently opened a box containing work by Eva Hesse made of polyester resin and found only “sludge.” The cold part of the museum is designed to preserve. But the very moment a photograph is made, her friend says, it begins to vanish. Next the woman flies backward off the treadmill. She steps on the plastic rim, goes down on a knee and shoots backwards like a star. She is not the oldest person at the gym but now she has fallen in front of the undergraduates. The young runners keep treading. Sweat and rubber. The woman gets up. She had stepped sideways before the belt zipped her airborne and turned itself off. There was a man who had arrived on screen. The figure in the reel came too close, and the woman dodged him. The video loop had updated. The footage changed and she fell.

119. The Conqueror

“To stab is an intimate action,” writes Dubrovka Ugresic. Finedictionary.com offers, as a historic example of the verb, a sentence from an 1878 issue of Chatterbox: “One bolder than the rest stabbed it with a pitchfork.” Above this sentence is a black and white illustration from a page of the same magazine, depicting French country folk bearing scythes and forks in a wheat field near Gonesse. Two laborers make haste towards the viewer. A pair of Cyprus trees are visible in the background behind the large, dark orb that fills the frame and spurts a long trail of hydrogen gas after being pierced by a farmer, bolder than the rest, wearing a wide felt hat. Before the balloon met its demise on the morning of August the 27th, 1873, it had been borne on a cart through the streets of Paris before sunrise, like a king, to the Champs de Mars: “A strong body of mounted soldiers accompanied the wagon on which the half-filled balloon was placed, while in front of it marched a body of men carrying torches…the drivers doffed their caps as they watched it pass.” The writer of Chatterbox imagines that the wily, uneducated farmers believed the downed balloon was “a large and unknown bird,” which had made a great sigh upon being pierced, confirming for them its living breath. After deflating the shroud, which had taken four days to fill with a gas lighter than air, the farmers tied the silk balloon to a plow horse and sent him running. “With wild excitement” they chased him through the field until the envelope had shredded. By the mid 1700s, by the time “poignarder” had faded from use, private guns were making way for the idea of private property across Europe. The personal firearm offered a cool threat from a distance. The gun made way for more impersonal brands of violence; the embodiment of privation. But Magritte did not suggest that his train “shoot” the dining room, or “open fire” from a distance. He hoped that the painting’s buyer, Edward James, would hang La Durée Poignardé at the base of his staircase, so the locomotive would “stab” his guests in the ribs on their way up to his ballroom. Instead, James chose to hang it above his fireplace, a decision that made the tensions between fore and background overt and shifted the painting’s referent to James’ personal property in the duplicate mantle below.

Of late and in the evening I've been reading Danielle Dutton's A PICTURE HELD US CAPTIVE, Kate Briggs's THIS LITTLE ART and Raquel Gutierrez's BROWN NEON. Deep in my head I am still reading Renee Gladman's CALAMITIES, Albert Goldbarth's MANY CIRCLES and Sheila Fischman's translation of THE LITTLE GIRL WHO WAS TOO FOND OF MATCHES by Gaeton Soucy.