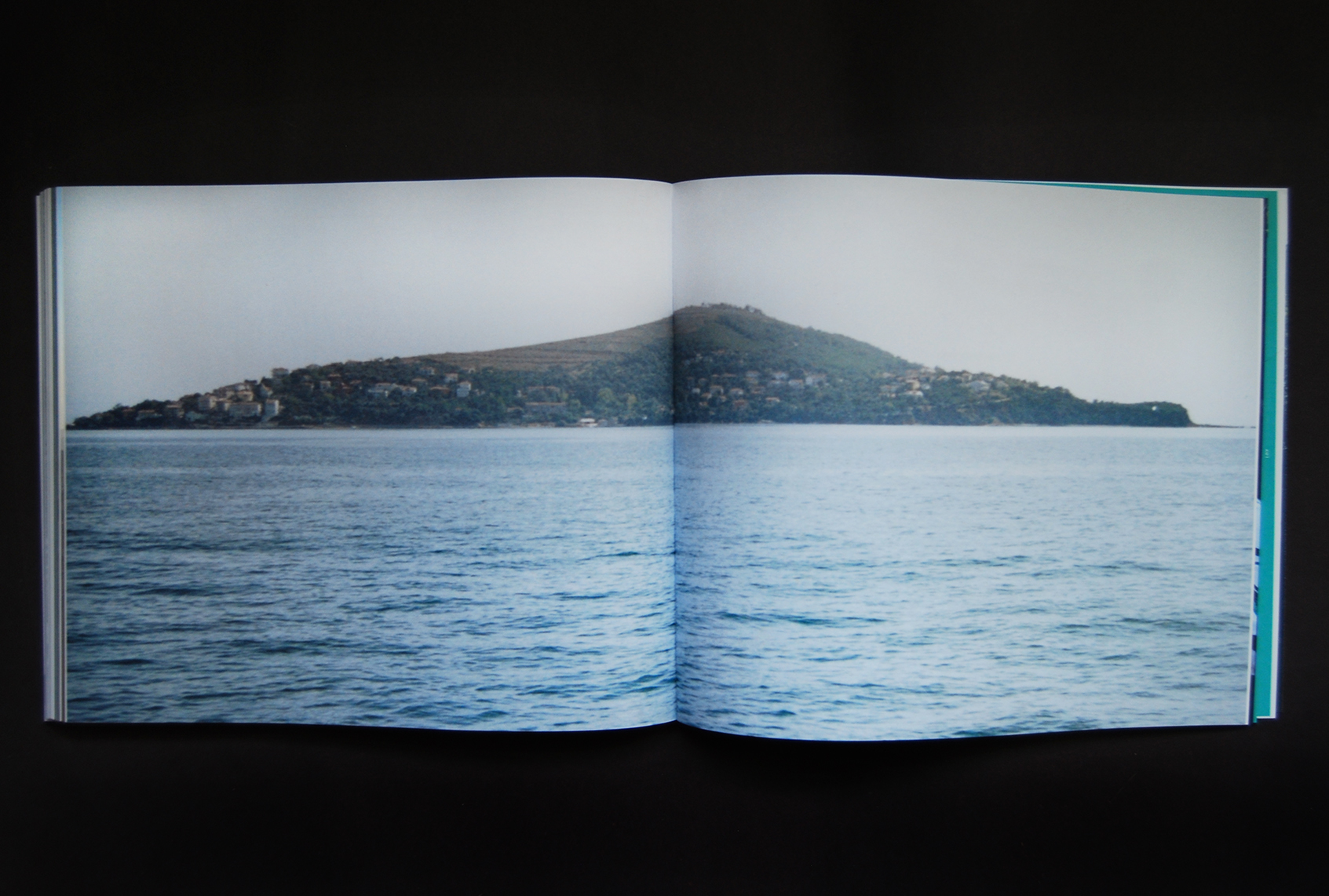

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

In 2012 I was new to New York and moving around temporary sublets in Greenpoint, using my lack of a lease as an excuse to meet people. Tom Haviv was one of those people. We never actually lived together, but he showed me his place and told me about a story he was working on. Five years later I saw some intriguing poems in Fence by a person named Tom Haviv. Was it the same Tom Haviv?

I wasn’t entirely sure until 2019, when I got involved with a fellowship for Jewish artists, the New Jewish Culture Fellowship (NJCF). When Tom and I reconnected through NJCF, we discovered our numbers still saved in each other’s phones: “Tom greenpoint” and “Nat subletter.” Tom, I learned, had been busy doing all kinds of amazing things since we met: co-founding a press, publishing a children’s book, and writing and designing A Flag of No Nation (Jewish Currents Press, 2019).

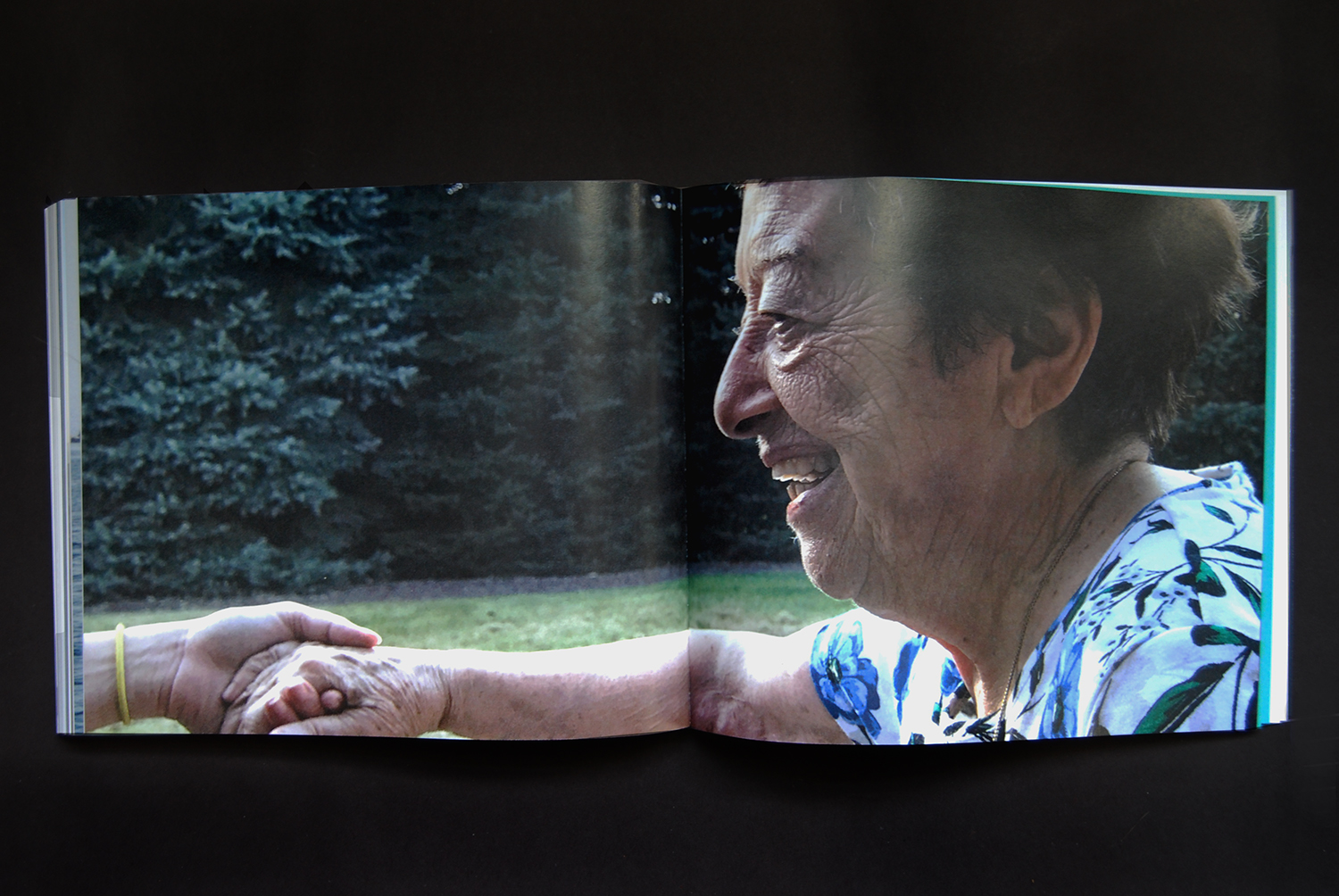

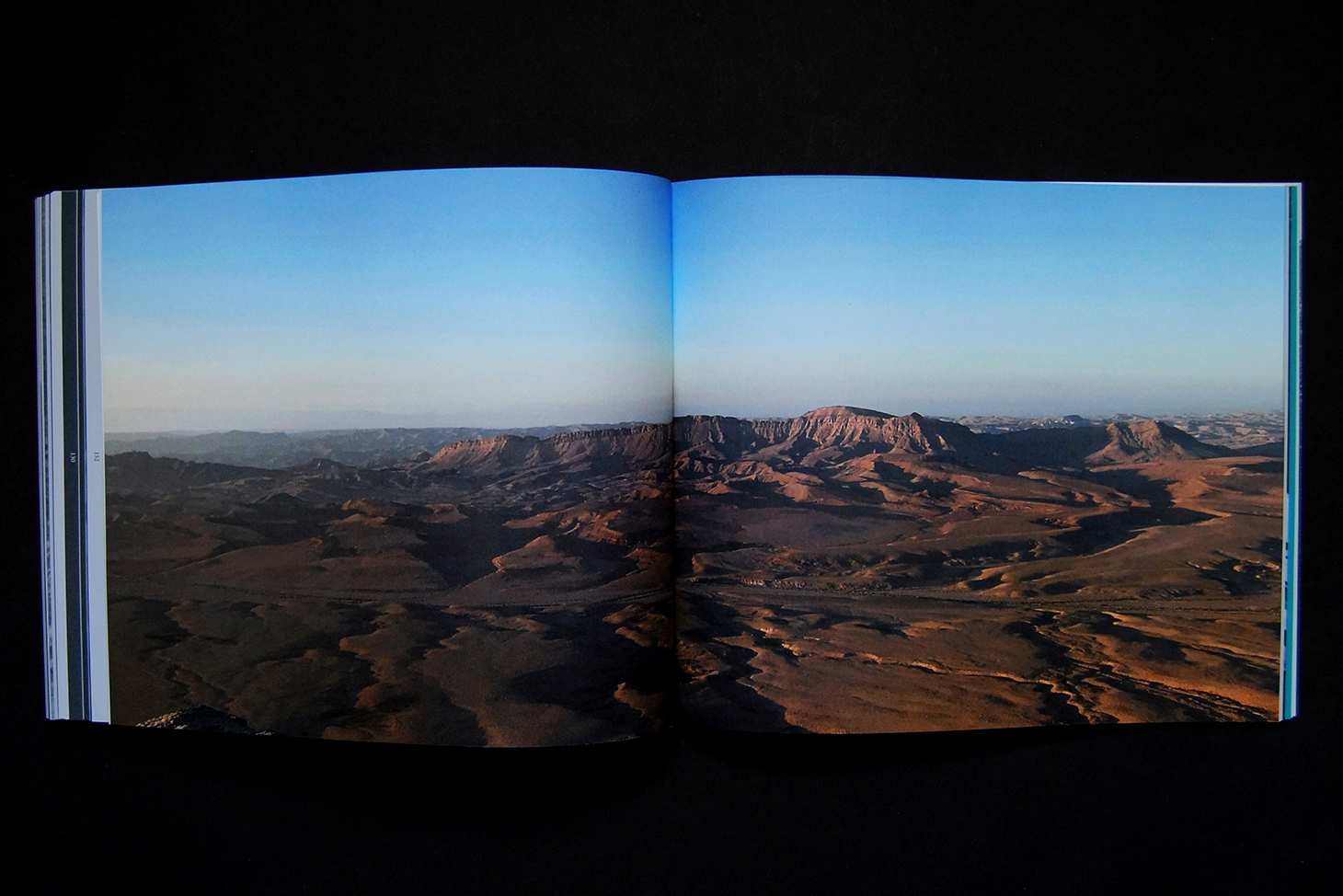

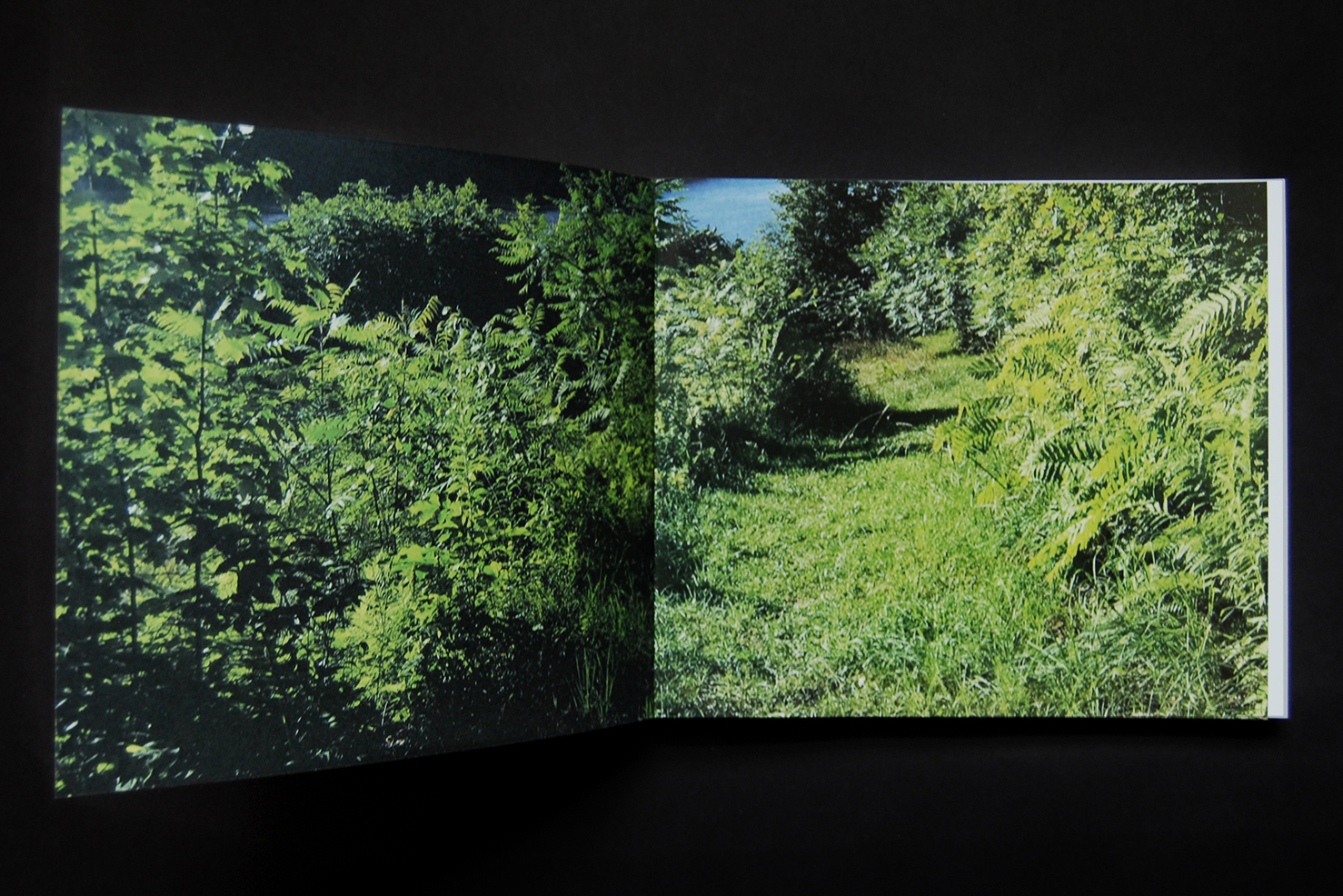

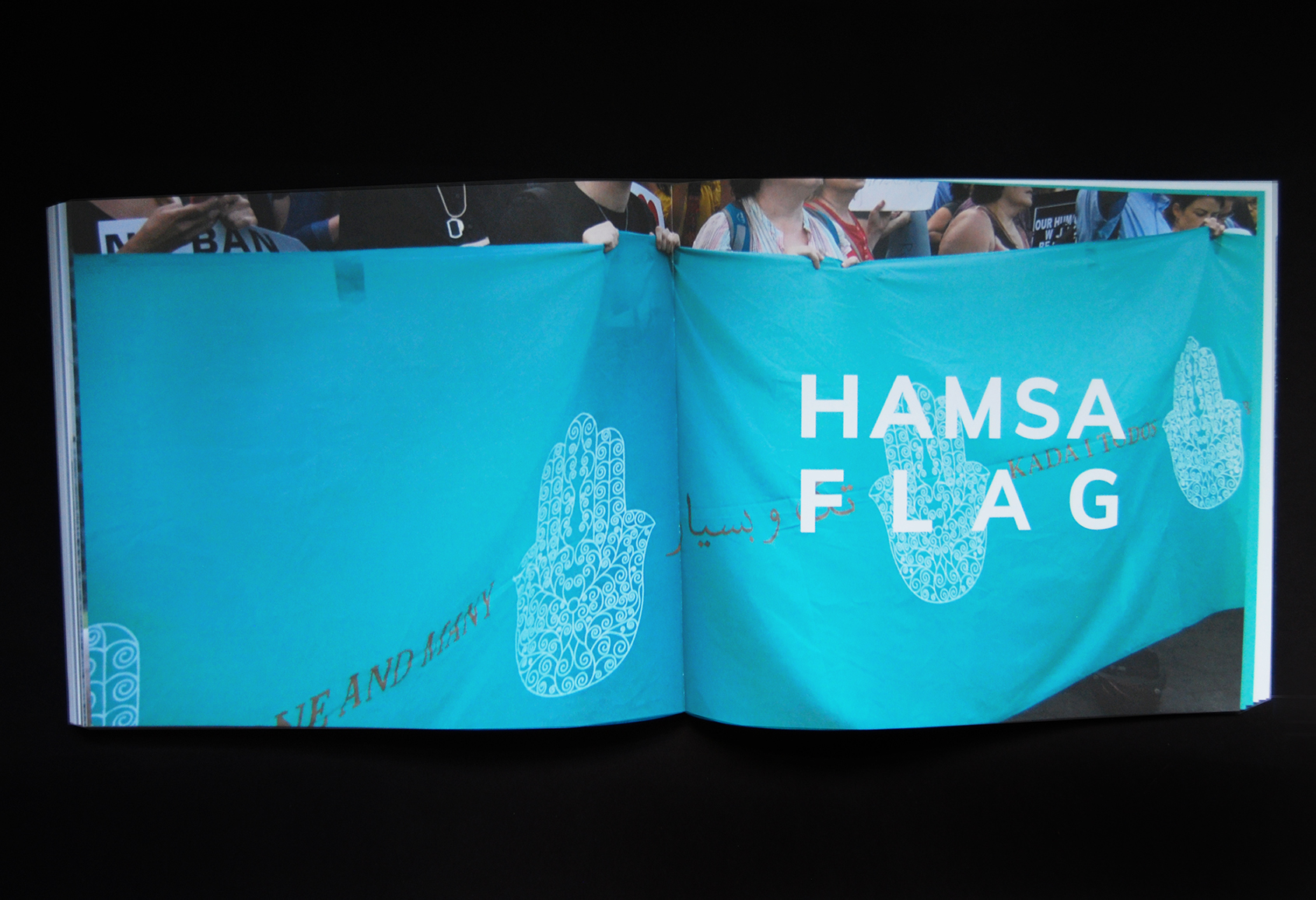

A Flag of No Nation is a book like no other—part poetry, part performance art, part allegory, part interview, part memoir, and part actual flag. It’s a beautiful object to behold, with a landscape orientation and full-spread photographs of Tom’s Turkish Jewish family. I am unaware of any other book that manages to pull off so many layers of hybridization. The book has seven sections: “Island,” an allegory of diaspora; “Losslessness,” a collection of interviews with Tom’s grandmother; “Ladder,” a lyrical reflection on Zionism; “Allegiance” and “An Arrow A Wing,” the story of his grandparents’ immigration to Israel/Palestine; “A Flag of No Nation,” a meditation on the notion of the flag; and finally, an explanation of the Hamsa Flag itself.

Inevitably, what began as an interview about A Flag of No Nation turned into more of a conversation—which is what our editor Menachem Kaiser wanted for us, anyway. (“Really no limit,” he wrote in an email.) It also turned into a record of the turbulent spring and summer of 2020. Over a few months, while Tom was in Vermont and I was in Brooklyn, we recorded four separate phone conversations, which meandered from A Flag of No Nation to my own manuscript Sky Access to our broader thoughts on art-making, trauma, and other spiritual matters. Those conversations, edited for length and clarity, form the mutual interview that follows.

--Nat Sufrin

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

Conversation I

4.24.20 @ 2:05 PM

“No single story will bring us to the promised land.”

Nat:

Something I find amazing about your writing—because it's not something that comes easily to me in my writing—is your broader political vision. I'm curious what writing politically has been like for you. I think it's something that poets can be afraid of. Auden's line that poetry makes nothing happen sometimes feels like our lame, inverted rallying cry.

Tom:

Are you saying that you think it's kind of the norm for poets and for poetry to avoid political questions, or different approaches to political action? I think my political engagement does set the project apart from a lot of books that are similar to it, in that it ends with the image of the Hamsa flag—a post-nationalist flag I created, inspired by my Sephardi heritage—which kind of exits the arena of poetry, carrying some residual poetic charge. But the whole idea of the flag is that it exists as potential energy. I've always seen it as an act of poiesis—to put something new into the world and see what it does. But I’m ambivalent about whether it's my job, whether the poetic work is to push the Hamsa flag into political reality, or social communal reality. As in, get more people to use it, institutions to adopt it, like that. Is that a continuation of the poetry? Is it all a big piece of performance art? Or is it social practice work?

Especially in 2013 and 2014, when the Hamsa Flag was starting to come to the surface for me, there was minimal relevant discourse around it in America. So it wasn't something I could easily plug into community organizing work. Later, when I kind of retreated from the idea that this was some sort of speculative design project, I started to think about what it meant that there wasn't a cultural context in which I could share this work. I think that's a lot of what this book is about, actually: the poetics of the book is that there's no audience for the book. Its poetics have something to do with dreaming of a potential audience or building the grounds for one.

So once I let go of it as a political project, I started thinking about the epic poem, and what it means to have a national literature. I was thinking of people like Bialik, the Israeli national poet, or even poets like Whitman, whose work represents a certain kind of national identity, which—even if it’s wrapped up in the most poetic, beautiful language—can get tangled up with violent superstructures, and the military industrial complex, and essentialized identities. And I started to wonder, what would it be to have like an anti-national, or a post-national, or a deconstructive epic?

Nat:

One immediate thought, from what you said about this book not having an audience, is that that's really the case for any book of poetry. This book, I would imagine, has more of an audience than most books of poetry because what it's doing with identity and nationalism is so interesting. Identity is king in so much of the work that’s getting published now. I was looking at some poetry from a first-book contest. And one after another of the previous winners had organized their book all around an identity. So a white man who grew up in Queens wrote a series of poems investigating that identity and background, and the way that the publisher couched the book was, "This is poetry from the neighborhood that Donald Trump came from."

Tom:

I think that's hilarious. Also, I'm just such a New Yorker, and I do want to talk about that! It's interesting to me that A Flag of No Nation has nothing to do with New York, actually. But I think that New York is why I was able to do this kind of work. But, I'm interrupting you. I'm with you. I'm following you.

Nat:

Tom:

No, no, no. I feel like in our last talk we talked about what exactly will it mean to “go far afield.” And for me, that means interrupting is fine.

Okay. Interruption is king and queen.

Nat:

Tom:

Exactly.

And the messenger.

Nat:

... and the jester. On one hand, your book is really coming from such a solid place of identity, and organized around identity. It's published by Jewish Currents press. And if your reader has grounding in this history, or in Hebrew and/or Arabic, they might have a richer experience of the book. For instance, I noticed you occasionally do wordplay with words that are similar in Hebrew and Arabic, such as the town in the allegory, Rimona—close to the word for pomegranate in both languages.

Tom:

Rimona is a made-up, re-gendered, version of the Hebrew word rimon, and a play on the way in which Eastern European and Arabic last names became Hebraized when Jews arrived in Israel/Palestine. I wanted to play with the idea that these are dispersed people, an archetypal refugee community charting its path into an unknown space. In Ammiel Alcalay’s After Jews and Arabs there's this Ashkenazi poet who gets to Palestine, and he's writing poems where he's reimagining the Palestinians as Cossacks and conflating the pogroms there with imagined pogroms to come—all this self-fulfilling prophecy. Whereas the Sephardic Jews who had Arabic last names, like myself, were already enmeshed in the same poetics, the same literature, the same histories. And I think the more speculative parts of the book are less about telling the story of this specific chapter in Turkish-Jewish political experience. It's trying to engage with the idea that our identities are not static, and that historical forces loosen them. And that we also can loosen them. And that the loosening of identities into other possible identities—like my grandfather shifting from this Francophile, kind of atheist, new Turk into a Zionist. That's an identity that will never appear again.

I think that there are some lessons there that I'm still trying to parse, about how to exist in specificity and in openness towards other ways of presenting oneself, slipping across borders and slipping across different community containers. Fundamentally, I have a naïve question: when will this end? When will this form come to an end? One reason my book goes back to Sephardic history is because it needs to go back to Ottoman history. The Ottoman imaginary. It’s very exciting to me to think: Oh, there were—and are—other identity containers, many of which we haven’t fully tried yet. And, perhaps, many more to come.

There are some kind of organizing principles and patterns that we get trapped in. We talk about hierarchies, and collectives, and the punishing version of capitalism. But we've changed the way we've behaved in even the past ten years. So my book asks to be read from a changing point of view: like, what would it mean if you wrote poetry, thinking about your ancestors from 400 years ago, and about the people you will be an ancestor for in the next 400 years?

That felt like it was getting to the territory of the epic poem, but in this way that's broken, in the sense that someone else will have to fill in the pieces. If it weren’t broken, it would be fascism, or it would be essentialism, or it would be some sort of violent conception of communities that we want to get away from. And I think that feels very Jewish: to build a broken narrative so as to allow the world we want to emerge through it. Also, to have some humility in it just being our own story.

There’s a line in the book that I feel proud of: “No single story will bring us to the promised land.” That doesn't mean that the journey is over. It just means that we need to tell a bigger story. And the story that's going to get us closer to the Promised Land for everyone, like a universal Promised Land, in the Jewish sense, of rebuilding the world, requires a much more complex way of approaching storytelling: on a bigger scale, with those empty spaces for people to enter.

Nat:

A couple of times you said something about something being very Jewish. And my response is, "Well, what does it matter?" I understand that nationalism is a relatively modern concept. It's only been around for a couple hundred years. But peoplehood predates nationalism. And I guess I'd like to know more about why it even matters to you if something's Jewish or not. I’m wondering how you square your feelings about nationalism with your investment in being Jewish.

Another thing is the marginalization of Mizrahim and Sephardim—Jews of Middle Eastern and Spanish origin—whose stories are brushed aside in favor of the majority Ashkenazi Jewish narratives. Your work is keenly in touch with this marginalization, and yet, Ashkenazi Jews, as you alluded to, didn't have the flexibility within the countries that they lived in that many Sephardim did. The political reality did not afford that to them. In many ways it makes sense that your hopeful, liberatory, identity-shifting project is the project of somebody who does come from that history, as opposed to me, who comes from Ashkenazi sources that are so traumatized—even though both stories intersect with the Shoah. But we'll have to leave that for next time.

Tom:

I will say briefly that I think it's also connected to the fact that I left Israel so young, and had the freedom to ask certain questions, and continue to have the freedom now to make certain kinds of art that I probably wouldn't have felt as compelled to make if I had become an Israeli.

Nat:

That's interesting, because it also sort of goes back to a kind of privilege, because you didn't have to serve in the Israeli Army.

Tom:

I mean, we could talk about that. That's a whole other story.

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

Conversation II

5.3.20 @ 5:02 PM

“What is the most mysterious thing that happens to a person?

Tom:

Thanks so much for coming to the reading the other night. Or whatever verb we use now for appearing. For your presence.

Nat:

Totally. I only caught the end, unfortunately. But I did recognize that poem from the book.

Tom:

I was going to say, that poem was written here a couple years ago. It ends with this natural imagery: the land sings as it lets broken things be reclaimed by it. I feel like a lot of the writing in that book talks about nature in this very abstract, virtual way.

Like the trees growing before peoples' eyes, in the “Island” narrative, and the creation of the landscape. These are all just visual tropes, they're more mythological than real. I think I had an impulse, when I was writing “Island,” to engage with virtuality. I felt an echo of that in Sky Access, its white space. There’s something virtual about white space, or literary space, and how it's aesthetically circumscribed as a black and white phenomenon: text on paper. Then the idea that both the blackness and the whiteness are essential, skeletal elements of literature.

That's why in the story of “Island,” the children named the island Vividness. That part of the book in particular feels very alive to me, because it feels indeterminate and concrete at the same time. Thinking about seeking vivid experience, and primary experience, from the black and white page, just feels almost painful... It almost seems like a mistake. Like a human mistake. Okay, we have this poverty in our experience, and that poverty might translate into suffering or trauma or disappointment. Or the Bob Dylan, life is sad, life is a bust thing. You know that song?

Nat:

Buckets of rain, buckets of tears.

Tom:

Yeah. Literature is this sort of compensation, or consolation, for disappointments in the real world. But what does it create? It creates a virtual world in which things are not actually vivid and real, they're still transposed from what we actually wanted, which was an integrated, real world that works. I guess that goes back to the Jewish shit about wanting an integrated world.

Nat:

Do we all necessarily want an integrated world that works? It's interesting that you say that “Island” feels like the alivest part of the book for you. Because I did have an interesting experience with it, where the first time I read it, I liked it, I sensed a lot of poetry in it, but at the same time, it was almost too much to get into.

Then the second time I read it, it just opened itself up to me. It becomes one of the entry points for the fact that the book is about so many different kinds of exile and you're about to go ahead and tell a specific Jewish story that's not told very often, among either Jews or non-Jews. In moments of reading “Island,” I would sometimes try to say, okay, well this is about this, but it never worked. I couldn't say, "Wow, this is about early Zionists,” or “This is about Jews fleeing Nazi Europe."

Tom:

I think the idea is to resist the overdetermination of history that is Zionism, that is that post-Holocaust Jewish kind of life. It's all back to the question, what does it mean to create a nation? Is it equivalent to making a coherent narrative? In the epic poem, are coherency or strength of the narrative the index or measure of how coherent and strong the empire was, you know what I mean? I wanted to investigate this idea of empire-coherence by getting into some of the more rickety mechanics of it, creating a kind of faulty machine that hopefully has its own dream logic.

Nat:

The silvered and the un-silvered people, where there's the two people who end up making love...Even though that's so symbolic, and there's so much you can read into, it doesn't turn into some cheesy love encounter. It's much more hedged than that.

Tom:

That is one of my favorite parts of “Island,” the section with the lovers. I think that it tracks, it matches with what I was saying before, that literature is a kind of exile from primary experience.

It's the first part, where people are taking a little detour outside of the historical linearity of things, the inevitability of things. Why does my grandmother have this story? Whatever the telos, the beginning, middle, end of the story is just going to happen. And when can a story unravel? It's kind of accordion-style, opening and closing how the narrative is told.

The other part of the lover section is like, why are they men? I think you're right, there is this sort of hedged eroticism. There’s also this communion with me and my grandmother; we're trying to tell the story together. But there's also this side narrative that's me and my grandfather. I wanted to think about a space where maleness is being investigated, where two different men are encountering each other in this ambivalent way that's different from the rest of the book.

Nat:

You would call the encounter between the lovers ambivalent?

Tom:

Well, there's a moment where one person is hard and the other person isn't. I felt like it was important, but I don't necessarily know what it means yet.

Nat:

The vividness that you're talking about makes me think about how your book uses photographs—unusual for a book of poetry. There are photographs of your family, photographs of nature. Especially the nature. In the beginning... Actually, the very first photograph, is that Vermont?

Tom:

Now wait a second. That's literally where I'm standing right now. I swear to God. I literally have just been hovering around this pathway down to the river… I'm going to send you a picture.

Nat:

I'd love that. I guess we should wonder what to make of that. It sort of makes sense because, well, this book is filled with places that are important to you. But the fact that you're in that exact spot makes things feel very alive.

There was another thread that I wanted to pick up, which is about the inevitability of your grandmother's narrative. I had the experience the first time that I read A Flag of feeling like, oh no, I've got to make sure to pick up people’s names, and follow the narrative, and part of why I love poetry is the lack of narrative. Or not the lack of narrative, but narrative not being necessary. But I stressed for no reason, because there was this seamless quality to it: those details didn't really matter. I'm not even sure if your grandmother uses your grandfather's name, or if the reader just learns it later. How did you accomplish that?

Tom:

It was very intentional. Obviously, “Losslessness” is my grandmother's oral history, so it's her story, I didn't fabricate that. But I did sequence the book chronologically, and I did title all the poems with names—mostly people’s names, but also a couple places. The issue of naming is pretty essential to “Island,” especially after one of the two lovers comes. We don't even know their names. We only know what their jobs were, and where they were in a hierarchy. The idea is: how do you become nameless, and in what way is that freeing? Then there are a few proper names that come up, Germany, America, and then Córdoba. All these different signifiers of empire and loss. But to me, they were always kind of like... Do you ever read Haruki Murakami?

There's a moment in one of his books where two characters turn up out of nowhere, and ones like, “Jack Daniels,” and the other one's “Colonel Sanders.” They’re imaginal, they're tropes. I wanted my characters’ names to clearly be tropes, even heavy-handedly. Then you get into this place where it's like, “he had no name”; then, in the last poem, “The Proper Noun of Love,” they're shaking out the logic of the violence of naming, distinguishing.

The kids are not naming the environment, but they are describing it. They're “enslaved by the need to describe,” right? That's their covenant. They're forced to tell the stories of the land because the last generation can't do it anymore. They can't do any of this informational retrieval. They can't report back about primary experience.

The people who sacrificed their primary experience created this ecstatic, improbable world that they can only experience and enjoy by having their children work and be exploited. I wanted to end with these more abstract poems, like “The Proper Noun of Love,” and then enter this whole environment of endless proper nouns. Like places, expressions, and names of the islands in the Bosphorus. I wanted the details of the poems to drift into music.

Otherwise I could've just written a book of nonfiction about my grandmother's story. That's just not what I do. I want readers’ imaginations to be loosened before they hear this story, rather than it just being graphed on from some preconceived notion of the kind of Jewish story it is, i.e. a unique Jewish story that's also post-Zionist, and this and that. While really, in a way, it’s a universal refugee story. In a way, it’s not even a Jewish story. It’s more intimate than that. You know what I mean? I think we were talking about this last week, about identity politics.

People are still really in this right now. I was just going to say, in some cases, history forces a person to identify in such and such a way. In some other ways, it opens up possibility, and you can slip into different forms. I wanted to make Yvette, my grandmother, a trickster figure, in a way. Even though she was telling a linear story, she could be telling a story that doesn't have to track with anything else. That’s the beauty of capturing a person's narrative and not doing much to it other than the line break.

Nat:

There’s a way in which you don't necessarily believe the story she's telling. I mean you do, completely. But there's a way in which—maybe it's the dreamlike quality of it—a way in which it's so specific, not a familiar Jewish story, and yet it's Jewish. When you touched on the fact that your grandmother had ambivalent feelings about your grandfather, I was like, "Yeah, that's right."

Maybe there is something about that that comes from listening to your grandmother speak. After a lifetime of close and constant interaction with history, she is very focused in her telling. I'm interested in the fact that it's a story that interacts with the Shoah, yet it's not filled with horror in the usual way. There are other kinds of more personal loss, like your grandfather’s blindness, which end up having a much bigger effect on the story. First, through the allegory in “Island,” and then again through your grandfather’s actual life and the operations and travels to try to rescue his vision. I was so taken with the use of blindness and the way that the personal interacts with the universal here.

Tom:

I would say the personal, in that case, is supposed to reflect the historical, and reflect the archetypal or mythological. But there is an omission in the book about their personal lives, how difficult their relationship was, and how unsuccessful it was in many ways. There is a line, “did they still love each other?” I had some kind of trepidation about sharing this book with family: most of my family’s not going to understand it. I didn't want to tell their story in a negative way. Their story has face value, without making this anti-Zionist, or post-Zionist, rewriting of their passions and their intelligence and their mission. The book’s supposed to do something that's more polyvalent—that honors them, but that looks forward into other possible stories.

It's a question that still feels real to me: what does it mean to have tried to make my family's personal, private history universal or mythological? It reminds me of something I read once about The Brothers Karamazov. The idea—I don't remember who wrote this—is that each of the characters is basically experiencing the New Testament over and over again. Every scene is a reflection of a different scene in the New Testament, but in Russia. And in Dostoevsky's mind.

I felt like that was something you could do with personal narrative. You could just be like, “what is the most mysterious thing that happens to a person?” and try to track where the sense starts to get lost, and this strangeness starts to get felt, and you're going to have something that feels mythological.

I'm sure every single person has that. Every single person has an irreducible strange place in their experience, and I think this one always stuck with me. I felt close with all of my grandparents. But I felt extremely close with my grandmother, especially in the years after my grandfather died and she moved to the States. We talked as often as we could, corresponded via email and on Skype. Our conversations felt like a lifeline for both of us. She was just marvelous, a linguist and a storyteller. And she had so many things to share.

I definitely felt a kinship with Izzy, my grandfather, as this formidable person who carried his suffering with pride. He always said, "I'd rather you be smart than be happy." I wondered about that self-abnegation. Self-sacrifice, maybe it's the immigrant story, on a level. The first-generation story where it's like, I experienced bad things, but that doesn't mean I had a bad life. It means that you're going to have a better life. Another kind of Jewish thread. When is the suffering this empowering point of pride, and when is it a sort of defeatist victimhood? This weird thing about taking pride in suffering is how your life gets shaped by it.

I also wanted the page to be shaped by his peripheral vision closing. I wanted the whole page to feel like a vision field, like a landscape, with text in the periphery, narrowing. I guess I'm wondering about the formal attributes of a life. What is the limiting factor that creates a coherent narrative, and a kind of inevitable trajectory? Do some people have pointed lives, created by choice or other kinds of limitations? Are there amorphous lives, where people just don't have any shape?

Nat:

My immediate thought is that when your life interacts with the forces of history so dramatically, as theirs did—and many people’s lives of that generation did, particularly the hunted or dislocated Jewish people—I think it makes it more circumscribed. Whereas our lives, for instance, I think you could say that they're more amorphous. They're more, do this, do that, figure things out as you go.

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

Conversation III

5.11.20 @ 5:30 PM

“I do believe that really well-wrought art can cause harm.”

Nat:

Back in the beginning of Covid, I was in denial about my dissertation deadline. It’s June 30th, and I mean, I wasn't really worrying about it in the beginning of quarantine because everything felt so strange. And now I have to. So the days feel a lot less full of possibility. Now that I’ve come to terms with it, and I'm working on it, it’s good. I'm writing about how the idea of the self differs in psychodynamic/psychoanalytic thinking and Buddhist thinking—and how this affects the way we work with patients. A lot of people have written about this intersection, but it was basically only one wave of people, one generation, people who were psychoanalysts who became Buddhists. It's something that came out of my own confusion as a beginning therapist and student of both schools of thought. There’s not a clear progression for the project, which is the best part.

Tom:

Are you engaging with Buddhist writing on psychoanalysis? Or just in juxtaposition—Buddhist-inflected therapy practices?

Nat:

No, I’m engaging more with classical Buddhist texts, at least at this stage. Psychoanalysts write a lot more about Buddhism than the other way around, but that’s not surprising. Buddhism is a few thousand years old—and a religion!—and psychoanalysis is not that much older than a century. Yet always in need of some revitalization.

I’ve been engaging with Buddhist writing and practice for ten years, but I can’t say I identify as a Buddhist. That kind of formalization would sort of spoil the fun. The term JewBu is terrible, but I do identify with the many seeking Jews who found something in Buddhism they didn’t find in Judaism.

There's a lot of issues around authenticity. With Judaism, I don't have to hesitate to call myself a Jew. But with Buddhism, Buddhism's something that I found, like many people in the West, on my own. It’s not my culture. Buddhism came into my life when I was in college, and it’s been helpful for me. But I don't often think of myself as a Buddhist because my practice isn't ritualized, except for the morning sits I sometimes do by myself. What’s your relationship to Buddhism?

Tom:

I'm not really excited about the idea of incorporating another symbolic spiritual system. I'm barely interested in doing that in a ritualized and traditional way on the Jewish side. I'm attracted to mindfulness, and the Buddha is interesting. But some of it just feels like a religion again. If I were to integrate things about Buddhism into my own experience, it wouldn't be called Buddhism. And I wouldn't be becoming a Buddhist. It would be learning about koans and the Blue Cliff Record. You know? I want to learn how to meditate. But I wouldn't want that to make me become anything.

Nat:

Exactly. What I enjoy about Buddhism is the practice of meditating and the reading of texts. And part of me is curious about joining a sitting group, but I would probably join a minyan first. Going to a sitting group brings up some of the same ambivalence I have towards attending any religious service. I grew up with a lot of prayer, every morning at school.

I went to a Jewish day school, my family kept kosher, went to synagogue most Saturdays. We were that rare thing: observant Conservative Jews! With Judaism, of course there's all the ritual and the prayer. But I think that the act that's prized above all is learning text. You see that in Hasidic communities and you see that, really, in any observant Jewish community. The idea is, the best thing you could possibly do is sit and learn Talmud. Not study, like for a chemistry test—but learn. And the Mitzvah is the learning. For you, you're saying that studying, or reading, and thinking about, and talking about this allegory of the Red Sea, that feels to you like a practice?

Tom:

For sure. It feels related to a bigger question about how poetry fits in with spirituality. I can’t really get into Mary Oliver or some of this affirmation stuff, it's really hard for me to read. The poetry that matters to me, it doesn't reveal itself so quickly. You know, whether it's Paul Celan, Lorca, or even Eliot. All that stuff questioned appearances, and perception. And also there's this profound relationship with naming and language. I bet you there's a cool hybrid contemplative practice that deals with language. I know that some kabbalistic stuff is about imagining letters and manipulating them. But so much of our experience with language, so much of my personal experience struggling with it, feels like there's some question about liberation there.

Nat:

Something that you were saying helped me with something I've struggled with for a long time. I had the same experience as you, being drawn to the writers, the poems that...you had to keep reading them, and they didn't reveal themselves immediately. Well, I'm just thinking back to my own mixed and somewhat shameful feelings about being drawn to poets like Celan or, for me, Wallace Stevens. There’s so much mystery there and there's so much unknown. Or Ashbery, I guess, is another example, though that's like its own mystery of a different mode. But there's shame in that kind of elitism of like, "This is better than Mary Oliver."

What I liked about what you were saying is there's something almost insincere in affirmation poetry—it's not really getting into things in the way that Celan is or in the way that Stevens is. And yet affirmation poetry can be very helpful for people. It has a utilitarian purpose. I think that's part of what's painful about being in the world writing poetry that is interested in mystery. And maybe you, as the writer, don't understand it either, and there are so many layers of self-doubt and self-hatred around that, because people want language to do something for them.

Tom:

Wow. Now we opened up some shit. I really can relate to everything you just said. It's not about erudition. My experience reading Eliot was crippling, almost. It was so intimidating to me when I was younger. And he's such an asshole. Whenever I read him now, I'm like, “This is very beautiful, but it's broken in all the wrong ways.” And also, I don't believe in the story he's telling. If I did believe in his story, I would think he was one of the best artists. But I don't. I don't think that even the best work of art is necessary if it's not telling a story that's liberatory. I guess it could be a step in someone's journey. But I do believe that really well-wrought art can cause harm.

I think it can cause major damage. And it was damaging to me. As I was getting into the book and at Brooklyn College doing my MFA, the first poems that I wrote were performance prompts. The most literary thing in the book is the allegory. And it was my effort to engage with literariness as I was taught it and as I was obsessed with it as a kid. But I had gotten to the point where it was hard on my body to write that, hard on my body to write the book. And it was such a hard process to publish the book that I'm not sure what message my body is getting from it. There are positive things, of course, but I'm having a mixed experience reflecting on it. And also thinking about how the book ends with the flag. It moves through all these forms and genres agnostically, on some level, but also to escape literature. You know?

And I also have felt a serious amount of shame around exactly what you described, being attracted to a certain kind of esoteric writing. And it’s felt alienating, it's felt confusing, it made publishing weird. It made relating to other people weird when I was younger. I had this experience—a memory just came to mind, in the spirit of psychoanalytic rambling. I was adjuncting at Brooklyn, I was broke as ever. I had no dollars at all. And I was working on “Island.” The process was hard. And my friend at the time, a journalist, really wanted to read it, and it took me ages to hand it over. But I finally gave her the poem and she read it really quickly and she was like, "I really like it. I don't really even like most poetry, and I really like it." And I cried. I think she was the first person who had read it who wasn’t my grandmother, or MFA people, or my parents.

But my feeling was, "I don't know why I write like this." I felt so much shame over the fact that that's what I wanted to make. And I just cried, because I had so much shame that it's hard for me to share it. I'm clearly on the far end of that story now, but it lingers. Really, I want to have a spiritual relationship with art-making, and some of that's going to be in language. I think the question about esoteric and sacred relationships with language is really interesting to me because—well, have you ever read the book Dictée by Theresa Cha? It’s almost like an Anne Carson book, it’s a lot of prose. It's amazing. It's one of the best books of poetry I've ever read. She only published one book. She was shot in the street, randomly.

But it's sacred poetry. Sacred poetry is different from regular poetry. It's different from history. It's not an epic. It's not a lyric. It's a sacred poem. It's not an affirmation. You know what I'm saying?

Nat:

No, this conversation around shame is... I'm so grateful that we wound up here because that's nothing I've ever quite talked to other friends about. It's so real, and it's very family-based for me. I'm doing this NJCF reading on Thursday. And I'm going to read the work that I sent you, Sky Access, a long and incoherent poem that approaches the Shoah. It's going to be weird for me. Lots of family will be there. They know about my trip to Poland, obviously. I emailed my uncle about it and he is so excited to come because he's so connected to the family history, but as far as I know doesn’t read poetry. I mean, who does? And if I stop and think about how he's going to react to it, it's scary.

I can't imagine what he's expecting. But in some ways, I think anyone on some level can understand what you were saying before about sacred poetry. When it comes to writing about massive psychic trauma and the Shoah, people understand that I’m not going to be just describing events and I’m not just going to be affirming. But I think that that's part of why it came out of me, because I’m feeling that shame, and thinking of people coming up on Zoom and being like, "What the fuck is this guy reading?"

Tom:

Oh my God. Well, first of all, they're not going to do that. Second of all, it's beautiful. And it's beautiful that you're sharing. I also can relate on some level. This book is in the hands of some of my family members. I'm sure they're like, "What the fuck is this?"

Nat:

Wait, I'm going to stop you, though, for a second, because I want to challenge one thing you said, which is, "It doesn't reach everything." I think that's okay. I've seen Mary Oliver poetry used in a therapeutic context, actually, as part of the curriculum of a mindfulness-based stress reduction class where they bring in lots of poems. I think I share your affinity for the darkness. Maybe because it goes along with mystery. But at the same time, it's nice for people not to get into shit all the time. Or maybe most people most of the time don't really want to get into things like that. It's not appealing. Maybe this is also a low view of humanity. But a Mary Oliver poem that's about going for a walk with her dog in the snow, there's a level on which I can appreciate that as a lovely still life. It's nice. It's not liberatory, but I don't think we always need to be searching. I don't think we always need to be going after everything. And, at the same time, there is liberation to be had in the act of taking a walk in the snow with your dog. Liberation is always at hand.

Tom:

You know what? You're probably right. And yet I'm not sure. I think it leads to questions about the relationship art has with healing. And if it does have a relationship to or with healing, that type of writing hasn't worked for me. And there are deeper traumas that honestly, maybe we do need to tackle, because we're pretty sick. You know?

I've just been dealing with depression my whole life. And I've made so much progress. And some of it just comes back and punches me in the jaw. And I can't work, I can't do anything. I'm basically at a point in my personal story where I don't know if anyone is ever fully healed. And that’s true of writing, too. Some of my book felt retraumatizing, and some of it feels healing and dignifying for my grandmother, and my family, and for me... But also I'm free of those questions, which feels liberating. And I can move forward. But it still hasn't gotten to the root of… I don't know, I'm still interested in what the roots of the questions are, and I feel like these fundamental traumas are motivating. I'm curious if you feel that way about your work, too.

Basically, I think my spiritual practice is about engaging with trauma. I was really interested in what you were saying about shame, and your attraction to that kind of writing. We’re Jewish men of a certain age with quite different experiences of Jewishness, but we have a relationship to ancestral trauma.

Nat:

Well, I wanted to ask you what you thought of Sky Access. And if you have mixed feelings, which I imagine you might.

Tom:

I found it moving. I have to say some of it I don't understand. I want to read it again. It feels like when I watched Mulholland Drive when I was in high school, and I was like, "What the fuck was that?" And I watched it again that same night. It's strange writing. It's strange and beautiful. The honest thing I was going to ask is what are you trying to do in the poem? It's funny and slapstick, and then about the Holocaust, and then about all these different types of idioms and relationships. But I'm curious about your actual writing practice.

Nat:

My entry into writing about the Shoah was looking around and saying, "Where is the Shoah poetry that I actually like?" Before I went to Poland three years ago, I hadn't read Celan beyond “Todesfuge”—”Black milk of morning”—his very anthologized poem. It’s funny that it’s so anthologized because he wrote it early on, it's very directly about the Shoah, and his other work is such a departure. But in any case, I was looking on some simple level, to write something that I would want to read and that was useful for me. I guess it goes back to the fact that mysterious poetry...actually, that's an absurd way to describe a genre, but I love it.

Tom:

It's absurd, and also, I think it is a thing. It has a lot of names. My phone is at 2%, so I should probably just let you go. But I saw a bookend. The bookend came out of your mouth, which was: It's of use to you, as far as I heard it, to write this way and to read this way. And what we were talking about at the beginning is of use to you. You said this about Buddhism, about meditation practice. So thinking about practices, it's like, "Okay, so this is a practice." What's the theological or spiritual story that's taking place when we're engaging with language like this about trauma, history, and I don't know what else? It's interesting to me because it can only be done that way. So my question is what does it do? What is it? What does it do for us? What is its utility?

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

Conversation IV

5.25.20 @ 3:20 PM

“It's amazing how you can see anything as narcissistic.”

Nat:

It’s a little strange for me to bring Sky Access into this conversation alongside A Flag of No Nation because it’s not a thing in the world in the same way. And it’s very awkward, to me, to talk about Sky Access, or to talk about my work in general. I think I'm a little attached to having a closed text and putting it out there on its own. I've fucked around with it enough. Not that I wouldn't change it, but I don't want to...I don't know…talk too much about how it came to be. There’s a fantasy that by doing so I might get in the way of the reader’s experience of the text. It makes me curious if you can relate to that at all, and what your experience is of being in a workshop.

Tom:

I don't mind talking about my stuff because sometimes, it reveals more about my own process and my intentions. I think it's interesting that you have that resistance. It makes me wonder what the function of the text is, and also makes me think of amulets. My friend Eden and I were talking about texts that are amuletic, they have those angelic Jewish alphabets that are not readable. They're impenetrable, and they're actually doing something to protect energy.

So it makes you think, okay, why do you want it enclosed? I can relate to that as well, back to the cryptic Celan-style poetry. There's the whole range of difficult types of poems, there's the koan, there’s the jargon-y poem, there are other esoteric modes. Some of them are deflective, and some of them are getting into paradox. But I guess I would be curious to understand better what it is that makes you not want to comment on it. Maybe you think what I'm doing with talking about A Flag of No Nation is grotesque or narcissistic. Or I’m diminishing the magic by adding layers of commentary. But commentary is Judaism. So what does it mean to make a poem that resists commentary? And what does it mean to create a Jewish poem?

Nat:

I don't see what you're doing with A Flag as narcissistic. I think you could see the impulse to be closed-off as narcissistic as well—as if my text is so special and I don’t want anyone to intrude on it. It's amazing how you can see anything as narcissistic. I don't think I want Sky Access to be sealed off. It just feels awkward to discuss it. For instance, the humor in it, that's not something that I intended. But I can see the humor in the grotesque rhymes, like in “Hey where / The hell / Did they / Go anyway // Pellets from a / Canister / Cannot / Erase dreams / From a womb the / Dream of the / Womb womb / Womby doom.”

I'm aware it's grotesque, but I didn't know that it could actually make people laugh. And to say that I wasn't trying to make people laugh feels like...Well, does that mean that people are laughing at me, in a sense? Does it still count as a successful joke if you didn't 100% intend it? And that’s part of what feels weird about talking about the work: I don't think intentions really matter that much. It seems like lots of people do. I think there's a sense of, you've got to be this master manipulator to be a good artist. I'm not really interested in that.

Tom:

But I still like talking about the intention. Because I do think that intention is part of creating a book. It’s a ritual or formal process. You have intention throughout. You have an intention to finish it. You have an intention to start it. Even if your intention is an illusion, it's part of encountering why and what creation is. But also, intention stops mattering once you let it go.

Nat:

Hearing what you just said made me think about how at my reading you remarked on the lines, “Unfortunately even one thousand / Paper cranes will not / Ensure you / Anything / Not even sky / Access / On a short-term basis.” I don't know if makes your experience of those lines richer to mention the experience when you're in Hiroshima and you see all the collected paper cranes that people across Japan and the world have made. It's a famous, symbolic demonstration for world peace and for anti-nuclear proliferation, making these paper cranes. And the term “Sky Access," I saw on a train in Tokyo. It was on the side of a train headed to the airport.

To me, there's a clarity in those lines. Unfortunately, all the fucking peace work you're going to do, all the memorialization or the mourning that's present in my own poem, isn't going to do anything, isn't going to put the souls of the dead up in the sky, even on a short-term basis. The short-term basis part came from the original sighting of “Sky Access,” because it had to do with something about privileges, sky privileges when you're flying.

Tom:

That's what I heard. In my head, I was like, are you talking about Sky Miles? It was kind of a joke about getting closer to the heavens.

Nat:

I'm going back now to Eliot, because there is a way in which all the allusions in The Waste Land are the point. There are a lot of insider-y things to detect and to understand. For the most part, I’m not doing that, I’m not making arcane references or using various languages. But I'm hoping to generate whiffs. I don't know, exactly, why I call it Sky Access, but I know that there's something there. It's like, where did all these ashes go? There's the line about the River Vistula, which I had a lot of experiences with, because it runs through Poland and right by Auschwitz and Zasław, the “camp” where my family was massacred and then my grandfather, his brother, and cousin were enslaved before they escaped. This is where my family’s ashes and so many Jewish ashes were dumped, and there's a line in Sky Access, “...the River / Vistula cannot / Dissolve a community / More.” That's a visceral experience—which I think a lot of Jews have when they're in Poland—which is, where the fuck are these ashes? They're in the wind. They're in the water. They're in the ground. But hopefully, they're in the sky, too. There's something nice about thinking that.

Tom:

My grandmother, when she died, we brought her ashes to the Mediterranean. She wanted to be brought there. So we took the ashes to a beach in Tel-Aviv last June. This all makes me think of John Coltrane, in 1972, he goes to Hiroshima and does this peace concert. He says basically, our message is Peace on Earth, and for that reason I want to specifically go to Hiroshima. He wanted that act to be a symbol of his work. He’s a Black man, an American from the South, recovered heroin addict, legendary musician, going, I want to play in Hiroshima and look at what America did. It’s not even his direct trauma. And speaking of impenetrable, yet liberatory and expansive things: free jazz. That’s the idiom.

I guess this all makes me wonder, what did and do Jews have to do with freedom music and freedom art? And what does that have to do with trauma? What does it mean for us to be still engaging with trauma, but actually still not having our freedom music, that's ours? We have this story of Zionism, which I am critical of, even though it's complicated. We're still wrestling with everything that's happened. But Zionism was and was not liberatory. I guess I'm curious, what's our John Coltrane “Peace On Earth” Concert in Japan moment where we pay homage to the traumas beyond us, that transcend us, which we are, of course, connected to?

Nat:

I think maybe I hear you wondering where the Great Holocaust Art is. Some is out there, for sure, but we’re also just getting started, I think. I mean, there is some great Holocaust art. There are many novels, for one. Lots of Israeli and American novelists come to mind.

Tom:

But there's so much of it that's not liberatory. And so much of it is not revelatory. And so much of it hasn't led us anywhere.

Photo of interior spread of A Flag of No Nation, Jewish Currents Press, 2019

Nat Sufrin’s poems appear in Fence, TriQuarterly, and Best American Experimental Writing. New work can be found in P-Queue and Allium. He received a 2019-2020 New Jewish Culture Fellowship and a Research and Travel Grant from Asylum Arts. He is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at The City University of New York.

Tom Haviv is a writer and multimedia artist based in Brooklyn and born in Israel. A Flag of No Nation is his debut book of poetry. He is the creator of the Hamsa Flag project, the co-founder of Ayin Press, and the author of a children's book called Woven.