He touched me, so I live to know

That such a day, permitted so,

I groped upon his breast.

—Emily Dickinson[1]

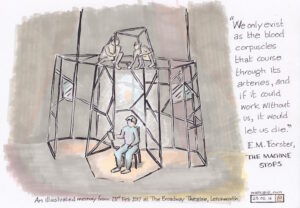

One of the first texts I had assigned for my 2020 spring environmental literarture course, Climate Emergencies, was E.M. Forster’s shocking visionary tale “The Machine Stops.” The story is set on a future Earth, the biosphere of which has been rendered uninhabitable as a result of some undisclosed catastrophe. The remaining human population lives below ground in individual isolated hexagon rooms—shaped like “the cell of a bee”[2]—where their physical, social, and emotional needs are managed by an omnipotent Machine. Not that this posthuman arrangement seems particularly distressing to these future humans. Most, like Vashti, the story’s protagonist, are content with their small mechanical environments, surrounded by speaking tubes and electric buttons that call for food, music, hot or cold baths, medicine, and clothing whenever they desire. This acceptence of extreme social distancing practices could be better viewed as ‘autonomous containment.’Like her fellow secluded citizens, Vashti is not a prisoner per se. She remains free, after all, to conduct remote lectures on her specialty—“Music during the Australian period”—to a distant audience using the Machine’s telecommunications system, a platform which now finds eerie parallels to contemporary online Learning Management Systems. More, Vashti can leave her containment: she is at liberty to visit the surface of the earth with a permit or travel the globe by means of an airship. Simply, she chooses not too. Vashti, like many netizens of this world—and I use the term ‘netizen’ deliberately here—prefers an immobile lifestyle, engaging with other telenetworked citizens remotely. As the story notes, Vashti “knew several thousand people,” with whom she can instantly silence communications by means of a personal isolation switch.[3] In this mechanically civilized world, social distancing has replaced intimate relationships.

Vashti’s only real complaints are the size of her bed—it’s too big—and her rebellious son. Unlike his tendentious mother, Kuno is an intellectually curious young man, who desires a universe of experiential knowledge-production that far exceeds his personal enclave. As he appeals to Vashti over their telecommunications system:

The truth is…I want to see these stars again. They are curious stars. I want to see them not from the air-ship, but from the surface of the earth, as our ancesters did, thousands of years ago. I want to visit the surface of the earth. [4]

Vashti’s displeasure of this excitable admission for exploration is obvious, and despite her stern warnings that the earth’s atmosphere is toxic, Kuno does manage to escape from the Machine’s underground civilization and successfully reaches the surface of the earth. Far from encountering a toxic wasteland, Kuno discovers ferns, keen air, hills that seem to him “living and the turf that covered them was a skin.”[5] Surprising still, Kuno also witnesses a surface-dwelling woman, who rushes to his aid, but is killed in the subsequent melee, when the Machine reapprehends and drags him back underground. Upon hearing this story, Vashti rejects his testimony. With Kuno now threatened with expulsion—or homelessness—on the account his betrayal of the Machine’s technocratic version of civilization, she punishes Kuno with a final act of social distancing: Vashti disowns her son.

Anna Christina Zimmermann and W. John Morgan have already noted the parallels between Forster’s fictional system of remote telecommunications with our contemporary social media platforms like Facebook and and Twitter, so I won’t rehearse their arguments here.[6] Suffice to say, Forster’s story is a technological parable on the dangers of yielding too much control to technology at the expense of intellectual curiousity and haptic experience. The autonomously contained humans in Forster’s future society—except for Kuna—have surrendered to their complacencies, allowing the Machine to supplant their own inventiveness, their biological and erotic desires with imitative ideas and counterfeit ideologies about the monstrosity of touch and human affinity.

These humans are not only living underground but have buried their heads in the proverbial sand. Their disgust toward proximity and physical contact leads to the perversion of social distancing, which at its most extreme deifies the Machine’s cold calculations and measurements over human reasoning. In the process, Vashti and her ilke have abdicated community responsibility to imagine alternative futurities in which empathy and change are the cultural forces that drive human interactions. Unlike her independent namesake, the Queen of Persia and first wife of King Ahasuerus, Vashti is symbolic of a colorless impersonal future. Devoid of critical self-reflection, she retreats into zealous familarity with her autonomous containment and intellectual subtraction, afraid of tactile sensations and situated experiences, which human-to-human contact enables.

That Distance was between

us

That is not of Mile or Main –

The Will it is that situations –

Equator – never can

—Emily Dickinson[7]

Forster’s underlying distrust of technology in “The Machine Stops” is not the least surprising given that his Edwardian society was itself swept up in a staggering technological and ideological tsunami. 1909 had seen a number of scientific and cultural accomplishments: automobiles were becoming common; Louis Blériot successfully flew across the English channel in his prototype aircraft; Ernest Henry Shackleton’s expedition reached the South Magnetic Pole; London’s Science Museum was established as an independent institution; physicists Ernest Rutherford, Hans Geiger, and Ernest Marsden carried out their famous Gold Foil experiments, which proved an atom had dense nucleus with a positive charged mass. Edwardian society was modernizing industrially, scientifically, and technologically at an exponential pace.

From a climate change perspective, “The Machine Stops” offers a glimpse into the early imaginings of atmospheric contamination coupled with dire ideological denialism. Its stark portrayal of a society in lethal contest over direct scientific observation and puritanical dogmatic determinism finds its purchase in our moment of climate denialism. Yet I find myself obsessing over this story not for its climate warnings but for its underlying narrative on social isolation. I haven’t been able to stop thinking differently about Forster’s take on social distancing since Governor Mike DeWine imposed a shelter-in-place order in my adopted state of Ohio on March 22 to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. While the Empire State Building dramatically shone its red-and-white siren in support of emergency workers on March 30, I saw our own Machine demanding the enforcement of new social distancing protocols.[8] True, the differences between Vashti’s situation in “The Machine Stops” and our moment are vast. I’m reluctant to draw easy parallels that elide the ribonucleic threat that is literally destroying lives violently in New York City and throughout the world. Let’s not be flippant. Yet I want to think carefully about Forster’s visionary portrayal of intrinsic empathy and imagine with the story—rather than against it—the tactile futurities made possible when social distancing in our mutual worlds ends. What does touch imagine? What radical empathy can be nurtured following the collapse of social isolation?

The distance that the dead have gone

Does not at first appear;

Their coming back seems possible

For many an ardent year.And then, that we have followed them,

We more than half suspect,

So intimate have we become

With their dear retrospect.

—Emily Dickinson[9]

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, my homeland, Aotearoa-New Zealand, has adopted the notion of the bubble as a way to describe how people ought to treat their social isolation and conceptualize their interactions with the outside environment. The bubble, as described by Prime Minister Jacinda Arden, is a mobile invisible capsule surrounding the individual as they leave their homes to attend to family members, perform essential services, and purchase groceries and medicines.

For the most part, Vashti’s bubble is stationary. It encloses her room since she, like her fellow netizens, avoids all physical social contact. As the story bluntly puts it, “[t]he clumsy system of public gatherings had all been abandoned.”[10] Touch is planned obsolescence. Social distancing has transformed into an extreme cultural practice in this underground society. Only Kuno breaks this holy contract. Exploring the surface of the quiet earth, he is momentary free from autonomous containment and touches the turf skin of this forbidden land with his body. Kuno’s rejection of civilization’s extreme cultural rules is thrilling, sharply contrasting with Vashti’s refusal of human-to-human contact.

When Vashti does yield to her son’s request for a face-to-face meeting, she does all that she can to protect the sanctity of her bubble. On the airship, she avoids direct observation of the exterior world. She protects herself from other passengers. More telling, Vashti aggressively eschews the empathetic touch of an attendant even when she falls:

When Vashti swerved away from the sunbeams with a cry, [the attendant] behaved barbarically — [the attendant] put out her hand to steady her.

“How dare you!” exclaimed the passenger. “You forget yourself!”

The woman was confused, and apologized for not having let her fall. People never touched one another. The custom had become obsolete, owing to the Machine.[11]

Concern motivates the attendant much as it did for the Kuno’s surface dweller, who rushed to his aid. But whereas Kuno recognizes compassion and affinity in his would-be rescuer, Vashti reads the attendant’s behavior as barbaric and uncouth. Touch, as the passage suggests, is an antiquated custom without a humane replacement. The attendant’s momentary lapse of socially-ordained distancing etiquette is for Vashti a moment of tactile horror.

Under some circumstances, touch can be gesture of love and kithship. Touch holds the potential for pleasure, for erotic knowledge, for direct experience and interaction with a universe outside of our bodies. For the first knowledge-worker—the infant—touch is their initial sensory-producing act that encourages self-reflection on one’s relationship with another world. However in the air-ship, touch is a mechanism of horrible knowledge. Vashti and her fellow passengers stringently remain isolated in their bubbles, “avoiding one another with almost physical repulsion and longing to be once more under the surface of the earth.”[12]

Where Vashti does experience touch under the Machine’s methodical care, it is a violent act, a cool medicinal horror from which she cannot emancipate. When she fails in her first attempt to visit Kuno due to an illness (either real or imagined), Vashti is momentarily stricken: “an enormous apparatus fell on to her out of the ceiling, a thermometer was automatically laid upon her heart. She lay powerless. Cool pads soothed her forehead.” [13] A doctor attends to Vashti remotely, forcing medicine into her mouth. This is not the care of a concerned hand, brushing against a hot forehead, but the remote coolness of modern telemedicine. The Machine misreads her emotional distress as physical distress. It is incapable of reflective concern because it lacks the imagination to recognize and empathize with her psychological pain.

I hinted Changes – Lapse

of Time –

The Surfaces of Years –

I touched with Caution – lest

they crack –

And show me to my fears –—Emily Dickinson[14]

In the end, there is the end. Following Kuno’s escape, the subterraneous civilization grows more resolute in its isolation, forbidding visitations to the surface and re-establishing religion with the Machine as its unquestionable deity. The needs of the Machine overrides the needs of its human creators. But with this new mechanical decadence, troubles begin to punctuate the society. The Mending Apparatus, tasked with repairing any defects in the Machine, breaks down, allowing multifarious mechanical problems, blighted air circulation, erroneous sounds, and deficient illumination to plague the secluded netizens.

Kuno, having relocated to a room close to Vashti, relays to his mother cryptic message: The machine is stopping. The Machine, the engine of human denialism and callousness, is dying . Social distancing isn’t an eternal condition, neither for us nor for Vashti and Kuno. As the Machine in Forster’s story begins to break down, the civilization it nurtured crumbles under the barrier of the world’s skin. The telecommunications system fizzles out, and Vashti, alone in her room, hears for the first time the authenticity of terror in the silence that overwhelms her. “[S]he broke down, for with the cessation of activity came an unexpected terror — silence. She had never known silence, and the coming of it nearly killed her — it did kill many thousands of people outright.”[15] When we’re no longer able to access Facebook or Twitter and when we are unable to post to Instagram, who do we have but each other? The end of social distancing is painful and violent for introverts and extroverts alike.

It is the Machine’s destruction that offers a glimpse into the moment when rules are uplifted, curves are quashed, and physical repulsion gives way to kindness and attraction. As the Machine disintegrates, Vashti crawls from her room, searching for her son in the darkness:

People at any time repelled her, and these were nightmares from her worst dreams. People were crawling about, people were screaming, whimpering, gasping for breath, touching each other, vanishing in the dark, and ever and anon being pushed off the platform on to the live rail.[16]

Paul March Russell describes this depressing conclusion as a reconciliation between mother and son, but the Forster’s finale is in fact far more transgressive.[17] The end of social distancing is a cut but it is also a moment of fluvial imagination in which the old world vanishes and a new one will emerge outside of the gaze of an unempathetic witness. For us, I hope it will be far less bloody. As Kuno lies bleeding beside his mother

His blood spurted over her hands. “Quicker,” he gasped, “I am dying — but we touch, we talk, not through the Machine.”[18]

The end of the Machine’s regime is a recovery of human-to-human contact, but it arrives with the violent end of a political order, the Machine’s and maybe our own. “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew,” writes Arundhati Roy, “It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” Perhaps that’s the lesson in Forster’s story. Imagination requires empathy, and the conclusion to social isolation comes with the anticipation of a novel empathy that follows a novel virus. Shared empathy holds the pain for the sufferer, not by means of heart emojis but through a collective act of imagining differently and radically against political expectations. In Forster’s final lines, I hear Emily Dickinson’s words. At the moment of their death, Vashti and Kuno realize that tactile intimacy is their expression of shared empathy and a beginning of a novel world order. As Kuno kisses Vashti, he reminds her what empathy continues: “We have come back to our own. We die, but have recaptured life.”[19] I hear in his lesson my misreading of Dickinson’s poem on love’s worldly expanse, its possible impossibilities to touch across oceans. In her letter, dated March 2, 1885, Dickinson writes to Mrs. E.P. Cromwell who was about to sail to Europe.

Is it too late to touch you, Dear?

We this moment knew –

Love Marine and Love Terrene –

Love celestial too –[20]

READ the full text of the short story “The Machine Stops”

READ Oliver Sacks’s article in The New Yorker about modern life and “The Machine Stops”

Orchid Tierney is an Aotearoa-New Zealand poet, scholar, and Assistant Professor of English at Kenyon College. She is the author of a year of misreading the wildcats (Operating System, 2019) and Earsay (TrollThread 2016), and chapbooks ocean plastic (BlazeVOX 2019), blue doors (Belladonna* Press), Gallipoli Diaries (GaussPDF 2017), the world in small parts (Dancing Girl Press, 2012), and Brachiaction (Gumtree, 2012). Other poems, reviews, and scholarship have appeared in Jacket2, Journal of Modern Literature, and Western Humanities Review, among others. She is a consulting editor for the Kenyon Review, and her website is orchidtierney.com.

[1] Emily Dickinson, “F349A—He touched me, so I live to know,” Emily Dickinson Archive [Click to see Dickinson’s original handwritten version of the poem, here and below].

[2] E.M. Forster, “The Machine Stops,” [Cited page numbers correspond to this pdf. After initial publication in The Oxford and Cambridge Review (November 1909), the story was republished in Forster’s The Eternal Moment and Other Stories, 1928], 1.

[3] Forster, 1.

[4] Forster, 3.

[5] Forster, 15.

[6] Anna Christina Zimmermann and W. John Morgan, “E.M. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’: Humans, Technology, and Dialogue,” AI & Society 34 (2019): 38.

[7] Dickinson, “F506B – Light is sufficient to itself,” Emily Dickinson Archive.

[8] Empire State Building, March 30, 2020.

[9] Emily Dickinson, “F1781A – The distance that the dead have gone,” Emily Dickinson Archive.

[10] Forster, 4.

[11] Forster, 8.

[12] Forster, 10.

[13] Forster, 5.

[14] Emily Dickinson, “F719A – If he were living – dare I ask,” Emily Dickinson Archive.

[15] Forster, 23.

[16] Forster, 24.

[17] Paul March Russell, “‘Imagine if you can’: Love, Time and the Impossibility of Utopia in E. M. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops,’” Critical Survey 17 (2005):68.

[18] Forster, 25.

[19] Forster, 25.

[20] Emily Dickinon, The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson, 1830–1885 (Amazon, 2020).