Dalia Neis and emet ezell are artists living in Berlin. This summer, they sat down to speak about Neis’ book The Swarm, recently published by The Elephants.

The Swarm hums to a music all its own. Set between the gurgling baths of Budapest and the Western Carpathian Mountains, Dalia Neis bends narrative into fog and mist. The Swarm is part film-script, part poem, part narrative: A filmmaker reflects on their relationship to desire. They dissociate during a lecture on the Holocaust. They float through tombs, cemeteries, and post-Soviet canteens only to return, relentlessly, to the permeability of the body in the Budapest baths.

In The Swarm, the baths provide both narrative structure and emotional gravity. Neis invites readers to consider a world in which there is no return, only a swarm of migrating birds on the horizon.

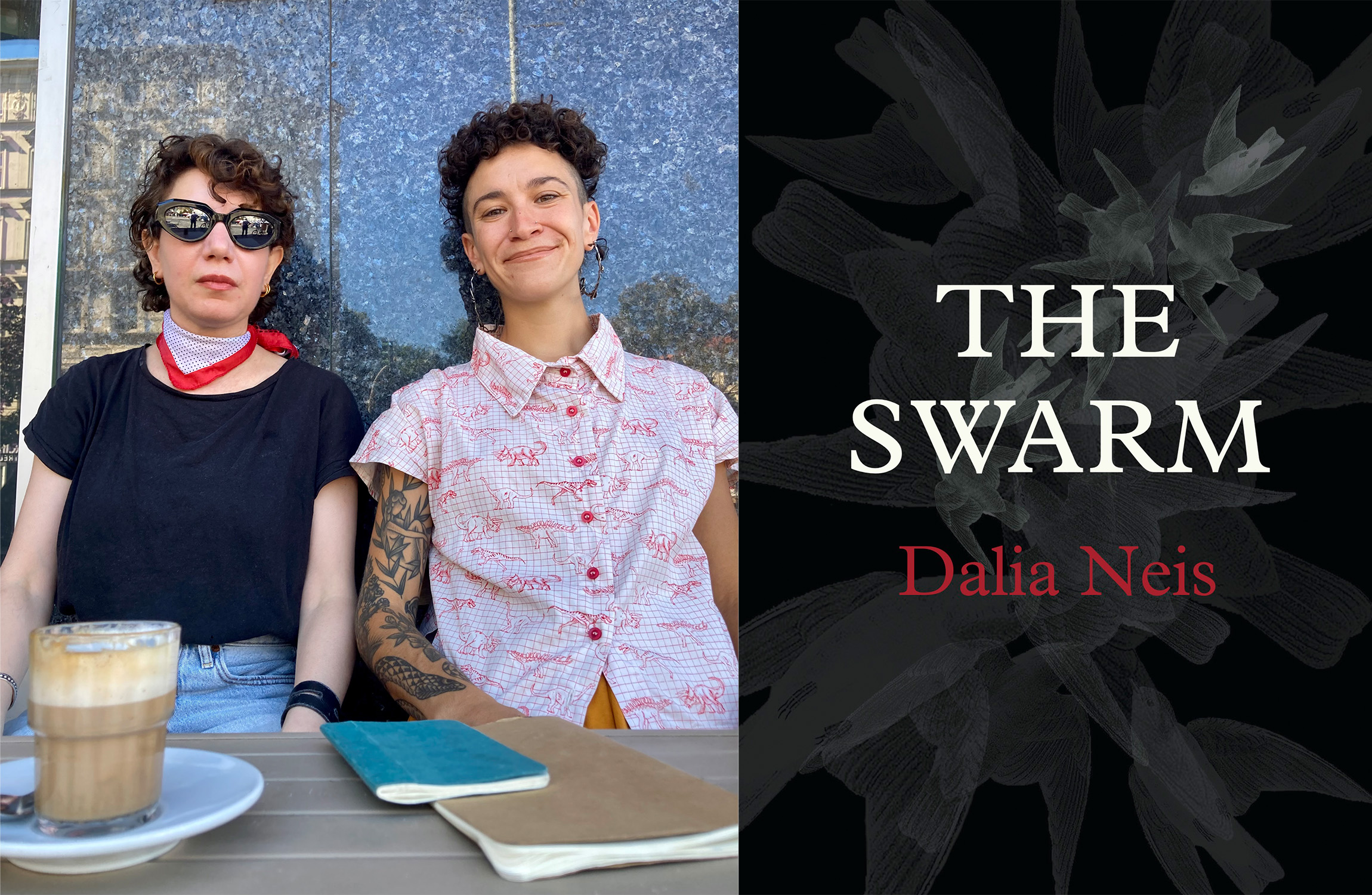

Dalia Neis (left) and emet ezell

Dalia Neis (left) and emet ezell

EE: Tell me about your relationship to Budapest and to the Carpathian mountains. What are these places to you?

DN: I have been drawn to the Carpathians as a site of literary and ancestral imagination since visiting my great aunt in Transylvania. My great aunt is one of the oldest surviving members of the Transylvanian Jewish community; I visited her there for the first time in 2011— on her 100th birthday. When I arrived, she was cleaning the streets with a broom. She cackled with laughter upon greeting me.

I was struck by this scrawny yet luminous figure in the streets of Oradia. I could sense the Carpathians rising behind her in the twilight air. This burnt a deep impression inside of me: a seemingly contradictory image of my ancestral history being suffused with the indifferent looming landscapes of the Carpathians, as if they were dissolving into each other. Then the vampires came in and a new mode of ancestral recreation began.

EE: Ooooh, I love this term— “ancestral recreation”— It feels related to what you write towards the end of the book:

If you are looking for childhood reminisces and familial narratives, you

won’t find them here. This is a leap into deep space.

A “leap into deep space” is something we discuss so frequently together— how are we to work with lineage in a way that is not overdetermined but imaginative and porous? Which gaps to open and how?

DN: There are multiple coexisting realities unfolding in the present time in The Swarm: an invocation of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Ottoman period, the pre-Roman Dacian period. The narrative takes place in Budapest, the Carpathians, Transylvania, across the Danube. There is no single focus point on a particular terrain. I didn’t want to drown in a narrative marked by historical tragedy, intergenerational trauma, and flights into nation-state frenzy. I wanted to write in a way that felt expansive, made up of a deeper, primordial geological aliveness that goes sideways into routes that intersect with other histories, peoples, species, places, and times.

EE: The Swarm opens and closes with a section entitled “credits,” creating a sense that it could be read backwards and forwards. Then in the middle of the book, you write:

The reproductive lines, the ancestral lines, the cracks in the bark… all

must be traced and then dissolved through a spell I was to recite in a

village square on the outskirts of town… No more nationhood pining.

No more homeland pining. No more pining…

I find this to be such a queer method of working with and through Jewish genocide— tracing and then dissolving, refusing to stay stuck in a ruined past or a nationalist future. This discomfort with the present brings to mind something Berlin-based writer Haytham El-Wardany has said— “that which is unsettled in history does not evaporate, but persists.”

An unsettled past echoes throughout The Swarm; and yet, at the same time, your writing undulates in new directions, refusing a singular position.

DN: I really enjoy your use of the word undulate. Yes – something that flows in spirals, rather than straight lines.

Your own poetry emits a vivid transmission of bird sounds, plants, and the inner landscape of trans embodiment. In your book, Between Every Bird, Our Bones, these themes circle around one another, creating multiple centers. So much of your writing sounds like a rhapsodic nigun (a Chassidic mystical melody), releasing not through climax, but through an undulating, wave-like intensity.

EE: So much of my Jewishness is bound up with song, with 18th-century tunes from Eastern Europe or Sephardic melodies from Portugal. These tunes generate a rhythm beneath my conscious body that influences and drives my poetic practice. When performing poetry, I frequently start by singing a nigun, invoking the past in order to make way for the present. Poetry and song are intertwined forces— both are rhythms moving through the body. Undulating, like we said. Can you tell me more about your relationship to music in your own writing?

DN: The Swarm was written in conjunction with songs for my eventual music project, Dali Muru & The Polyphonic Swarm. I hadn’t planned to make an album, but this process happened simultaneously, almost by impulse –– melodies arrived, lyrics emerged that became songs, and songs became soundtracks for stories and poetry in the book.

EE: The songs really are a soundtrack. They offer a mystifying and cinematic companion to the text, an entirely different experience of the work. The Swarm transports me into the monstrous. You write:

A hurricane spat me from my suburban home in Buda into the gray

center of a trembling pine forest. Then leaves shot through my cheeks.

Branches sprouted through my torso.

Body and the landscape collapse into one another, forming a hybrid organism. Lately, I’ve been biking to Plotzensee each morning to swim. It’s a 35-minute commute from my Berlin apartment. I bike, I swim, I bike back. I initially thought my swimming practice was going to be restorative. However, when I slip my naked flesh into the lake, I’m ravished by this consuming fear that I will drown. Algae bites at my feet. A cormorant dives below my belly. My breath comes out in hackneyed gulps. The water is a womb that carries other voices, other beings, other ghosts. In my morning swim, I sense this permeability. I perceive it in your writing, too— especially when you write about the baths.

DN: Spirits and beings surround us all the time. In The Swarm, I’m in conversation with a band of beings from different places and times. These beings include Shoshoah, a factory worker and Jewish resistance fighter from the Austro-Hungarian empire, Rekas, a contemporary trans-Roma musicologist, and Banshee, a mythical figure in a more-than-human body. These figures came to me while bathing in the baths of Budapest. It was important to me that The Swarm carried this polyvocal quality, this sonic dimension.

EE: So much of The Swarm displays, as you call it, “the link between pantheistic rapture and revolution.” I’m so interested in the relationship between devotion and revolution, between Spirit and uprising. You write:

Revolutionary thought is at its most potent if you allow yourself to

surrender to it.

Can you say more about this surrender?

DN: This quote is pulled from a sequence about the baths and the “geological froth” in the water. It is about the brain literally softening through the body’s contact with water.

In this particular, speedy climate of late capitalism, slow and soft activities like bathing seem like a trivial luxury that only panders to the tourist. But it actually is a communal need, and is very much part of the multi-generational, daily lived experience in Budapest, inherited from the Ottoman period.

Bathing culture is a people’s pastime, and deep, collective encounters can happen there, cultivating the potential for expansive and subtle registers of transformation; a form of slow activism can happen there if you allow yourself to surrender to it.

In the first half of 2020, right before the outbreak of the pandemic, I was invited to teach film in Budapest at the Central European University which was then shut down by the Orbán government. There was a massive student body protesting, and a true sense of revolt filled the air. This was soon after completely crushed by the government.

During this tumultuous period, I spent every day at this medieval Ottoman bath around the corner from where I lived in the hills of Buda, and found a growing sense of community in this bathhouse. I was struck by how my body seemed to have craved the medicines of these sulphuric waters. As I dipped my head into the bath, my brain took a submarine ride into my feet, and a sense of a vivid geological expanse took hold of me, soothing and softening my nervous system. Bathing also became a key method in my writing process.

EE: There is always a spiritual component to transformation and I think our job as artists, as poets, is to illuminate that invisible register. To trace the spiritual blueprints of disinheritance. We take the risk of making ourselves available to the primeval realm and its imaginations, transcribing messages onto the page. For me, this process materializes in the quiet, in the periphery: the corner of my desk at 4:00 am when all the candles are lit..

DN: Yes – and this mode of transformation can widen out to a communal scale; uprisings also do happen in seemingly peripheral places such as the bathhouse, as well as on the streets, and it can happen when you invite the dead and other anomalous beings who are aligned with the struggle for liberation – we need to summon our support team!

Recommended Reading

Dalia Neis: The Book of Embraces by Eduardo Galeano (trans. from Spanish by Cedric Belfrage)

emet ezell: A Musical Hell by Alejandra Pizarnik, translated from the Spanish by Yvette Siegert.