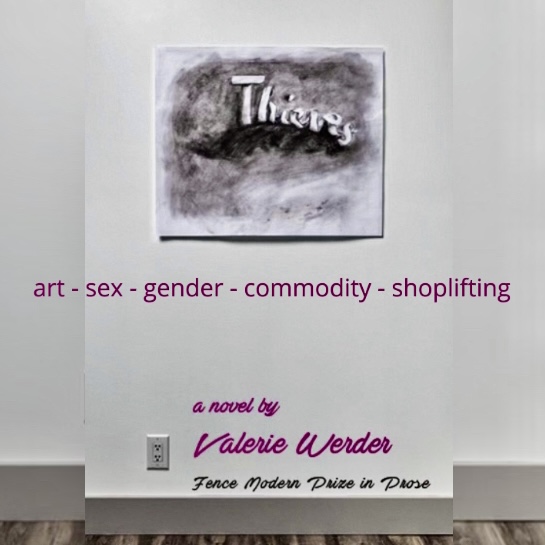

On the eve of the publication of THIEVES: A NOVEL, author Valerie Werder and Fence Editorial Co-Director Jason Zuzga connected to discuss the origins and complex life of this work.

JZ: You were working in the art world when you wrote Thieves—how did your experiences lead to the writing of the novel?

VW: I wrote the first draft of the manuscript in two and a half months in 2016. I’d been working at a blue-chip Upper East Side gallery for about three years at that point, where I had originally been hired as an assistant to one of the directors, but the gallery’s CEO soon realized that I had this uncanny capacity to ventriloquize her voice, or the brand’s voice, and she stole me away to be the “voice of the gallery.” My job was to produce texts—press releases, letters to clients, interviews for magazines, sales notes for artworks—that pushed the theoretical and art historical vocabulary I’d picked up in school and in my very minor existence at the art world’s periphery into an approximation of her way of speaking.

Of course, I’d learned how to write essays in high school and undergrad—I had the typical experience of a young person in the U.S. being drilled to produce language in specific formats and under tight time constraints for standardized tests or term papers. But being the “voice of the gallery” put me in a totally different relationship to language. I wasn’t being asked to craft an argument or perform an intelligence that would be linked to my name—being a brand’s voice was somehow both a more instrumental use of language, insofar as the texts I produced were literally sales tools, and a less instrumental relationship to language, since nothing I wrote had the burden of representing me, my ideas. Language suddenly had very little to do with me, even though it came from me.

JZ: Was this situation as awful as Valerie’s void ventriloquism is for others? Or worse? Were there any positive aspects to your job?

VW: Well, it taught me how to write. I don’t have an MFA and had never taken a creative writing class: I learned how to really relate to language as language, as an autonomous material, by working as the voice of the gallery. But it was a miserable, extremely high-pressure environment, and I was frustrated by my growing realization that the language I was swimming in had both nothing and everything to do with me—I worked all the time, very long hours, and writing this way felt like a brand voice was at the helm of my mind. This is how consciousness works, I think, with the self as a kind of walking bibliography, but this experience was quite an extreme version of that. When you’re occupied by a particular voice all day, that voice eventually becomes coextensive with yourself. I felt like an animate press release, and I was both repulsed and fascinated by it.

I don’t think that writing as the gallery cut me off from some formerly free-slowing and natural voice that originated inside of me. I’ve never felt in possession of a coherent and single “voice.” In actuality, writing press releases, letters to clients, sales notes, and so on implanting a highly productive voice within me. Because I was under immense pressure to produce text quickly and with little advance warning—a gallery director might decide they wanted to show a client a painting that’d just come in that morning in the afternoon—I knew exactly how much text I could produce in an hour, or in a day, and knew how to will myself into the state of producing that language. I felt less like a writer than a language machine, a kind of sieve or processing device. I would often plagiarize myself, as Valerie does in the novel, or grab existing language from a sketchy website or old exhibition catalogue and rework it into the gallery’s voice, which became synonymous with my voice.

JZ: What made you decide to write the novel?

VW: About two years into working at the gallery, I met the person who roughly corresponds with Ted. He had all of the wonderful and contagious optimism of a con man, and he convinced me that I should take this new skill of producing a continuous stream of language away from my boss and use it for my own purposes. Seize the means of language production, which was myself! We hatched up a plan that I’d tell my boss I’d gotten some prestigious writing residency and needed a three-month sabbatical. Of course, I didn’t actually have a residency lined up. I’d never even applied for a residency. I’d only ever written one short story! But a friend of a friend had a tiny cabin on a queer arts commune in Tennessee that I could rent very cheaply, and another friend had a car I could borrow, so my DIY residency was born.

While I was in Tennessee, I didn’t see or interact with anyone, save for two donkeys who came to greet me on daily hikes. Aside from hikes and weekly grocery runs, I stayed inside with the wood-burning stove going, writing. I was totally single-minded, because I knew this might be the only time in my life I’d have a long stretch of time without work. Sometimes the only person I spoke to all week was the cashier at the local Walmart. The internet failed during an ice storm in my first week at the cabin, and I didn’t get it fixed. I took down all the mirrors so I wouldn’t even be able to see my own reflection. I wanted to literally disappear into language. I think of language as something that is autonomous from me and indifferent to me. It never originates from within—that’s why I love writing so much. I can lose myself in language and submit myself to it, rather than instrumentalizing it to make myself visible or representable. I thought a lot about Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit—like her, I wasn’t necessarily trying to escape embodiment or purify myself from external influences. I wanted to set up conditions under which I could produce language in a voice that would be called “my own,” but totally unselfconsciously. I was interested in writing a book because I’d done so much short-form, fragmentary writing at the gallery, and wanted to see how these consumable, fragmentary texts could be layered and accumulated into something more dense and unwieldy.

JZ: How much of the narrative did you have in place before you began?

VW: I didn’t begin with an outline or any idea of where the text would go. I worked on each chapter as a distinct entity and began shifting them around until it felt like a larger form was emerging. The only preparation I made before beginning was to Google the word count of some of my favorite books to get a rough estimate of what I should be aiming for. I timed out how long my sabbatical was against how many usable words I knew I could produce in a day—around 1,000 or 1,500—and figured I could push out around 85,000 to 90,000 words in two and a half months. I didn’t give myself days off or sit around waiting for inspiration to strike or map out plot points and ruminate over structural problems. I simply typed and arranged.

The chapters are all quite short because the texts I was accustomed to producing for the gallery were quite short. I remember there was a big debate as to whether press releases should be one or two pages. One of the directors really wanted paragraphs to have a symmetrical shape—as in, the final line of each paragraph needed to meet the right margin. I had been trained to pay close attention to the visible appearance of the page, which meant that I was highly attentive to the form that was emerging as I worked on the novel, like a sculptor.

I used the same self-plagiarism and found-text methods I’d used in gallery writing to write the novel. For example: most of the emails in the book, especially the spam emails, began as actual emails I received from Wells Fargo or some wellness influencer or whatever. When I was still at the gallery, I’d receive these emails at my desk. My computer screen was clearly visible to the directors, and I had to look like I was working at all times. Luckily, doing my own writing could very easily resemble “working.” I just had to have Outlook or Microsoft Word open, and I had to be typing. So, I’d open these emails and begin revising them, building them out, making them spin into strange and hallucinatory places. It’s funny—now that I’m explaining it, this writing practice sounds quite close to the practices of rebellion Valerie tries in the book—inhabiting the semblance of compliance and productivity without actually generating value or doing what you’re supposed to be doing.

JZ: Your name is "Valerie," your protagonist’s name is also "Valerie." To what extent are these two Valeries similar, and what are some of the major differences between the two of you, if that would be the right way to put it?

VW: I have a difficult time figuring out where I end and the “Valerie” who operates in the text begins. It feels strange to refer to her as “the protagonist” or even as a “character.” It’s not that the book is a memoir and that everything in it really happened. It’s more that, in the process of writing, it became clear that grappling with Valerie in language would inevitably change me, too. We’re not stable or distinct entities. We’re wrapped up in each other, in much the same way that she’s wrapped up in “the sales game.”

JZ: That sounds very much like the problem Valerie grapples with in the book: that language is a problem for this "Valerie," as well as being part of the core of her being. As she attempts to scrape away social construction and “the sales game,” she finds yet more layers that determine her exchange value.

VW: When I wrote the book, I was utterly embroiled in the language of sales. In the context of contemporary art, poetic ekphrasis is a trick for creating value. I had become expert in the process of producing an object’s value—and so, to some degree, producing the object as itself, as art—by translating it into this consumable language. And at the same time, I realized that part of my role at the gallery was to be objectified alongside the art objects, to become a kind of mediating object that served up art objects for collectors.

JZ: Do you think that there is any escape from “the sales game” or “the getting game”?

VW: I’m not sure—definitely not at an individual scale, but maybe collectively. A book is an individual endeavor, though. It’s now a commodity copyrighted in my name. When I was writing the book, I needed to grapple with the fact of both being an object and translating objects into language, which also meant translating them into monetary value. I wondered if translating myself into language would do the same thing, and I guess it did, because I spent the entire day yesterday working on building an author website with a readable biography, a list of things I’ve written, an image of myself that I took for the specific purpose of having a face to wear on the Internet. All of this is meant to make me consumable so that the book can reach readers. And I want the book to reach readers, partially because I think the efficacy or purpose of an art object can only be measured by how it operates in the world—the book is its own thing now, with a life distinct from my own—and because I’m still wrapped up in the sales game. We all are! Money isn’t real, but it has real effects in the world. I have to pay rent, buy groceries, buy clothes! So Valerie isn’t the only version of myself that exists and circulates separate from my physical body. My website, this interview—it’s all linked up in the sales game. I think of Valerie as the catalogue-essay version of myself, the sales-note version of myself. She’s made of the same language that constitutes me, but extracted from my physical body. She’s a flattened out version of myself.

JZ: What about the other forms of language Valerie makes use of in the novel—her journal entries or dream records, for example?

VW: You’re right—I don’t think that the sales note or catalogue essay is the only linguistic form in which Valerie exists. Like me, she’s a compulsive chronicler. I’ve kept journals for as long as I can remember—I really enjoy the process of watching a written self accumulate and change over time, and I enjoy that these journals are a physical, material fact—they’re sculptural. Language is not only a sales tool—it’s also a bodily excretion, something like food that’s consumed and then both filters through and nourishes the body. Ottessa Moshfegh has this great manifesto in which she compares writing to shitting. I like that idea a lot. Adrian Piper has a similar piece at MoMA called What Will Become of Me, in which she saves her fingernail clippings and stray hairs in jars and sends them to the museum. I think that’s kind of like using parts of one’s journals to create a book, which I did—taking one’s bodily excretions and transforming them into art by putting them in a particular form, a particular institutional context.

Most of the artists and writers I really love are prolific journalers. I feel the same way as Louise Bourgeois about journaling. I’m not interested in analyzing myself. I keep journals to be in a continual process of putting myself together outside of my body. My journals feel like an ongoing conversation with an externalized version of my voice, like talking to myself over time, and seeing that “self” split and transform over the course of a lifelong conversation. Writing produces more writing; language produces more language. It would be really simplistic and arrogant of me to think that the language I produce comes from “me.” Language comes from itself. It’s autopoietic. I’m not really concerned with content or story or character or the relation of any of those things to the “reality” of myself, my life, as much as I am interested in what happens when I take certain experiences and put them to language—what happens to language once it gets going? I’m not sure what my role is in this process, or how the “me” that writes is different from the “me” that is written. That question feels kind of unimportant to me.

JZ: Do you see multiple Valeries in the book? Which one feels closest to yourself?

VW: The sections about Valerie’s youth—up until the point she meets Ted—and the bits about her work at the gallery hew closest to the “true” story of my life. I didn’t make up any of the art-world stuff. I think I was rather tame in what I included, actually! I didn’t want the novel to be an expose of art world exploitation. I have an aversion to spectacular representations of violence and juicy stories. I was much more interested in mapping the pervasive, low-level coercions and manipulations in which Valerie finds herself entangled. My friend Sylvia Gorelick said this great thing once about politicizing extremely mundane interactions in writing as a power move, a kind of operation in a chess game. I was thinking about artists like Aliza Shvarts and writers like Lynne Tillman who render themselves into autofictional shifters in order to map the social relations in which they’re imbricated, and to find a way in which to move within this constrictive social map.

The story of Valerie’s involvement with Virginia and Ted is probably the most fictionalized part of the novel. It’s not that the characters themselves, or the situations in which they find themselves, are invented, though. By the time I was working on the final revision, more than six years had passed since I wrote the first draft. I wasn’t 26 anymore, and I didn’t feel close enough to Valerie to keep treating her as my textual shifter. I had to bring in Virginia so that I could have a stand-in inside the text. So, it’s less that Virginia and Ted are invented, and more that Valerie and Virginia were both necessary to map the ways I related to the person in my life from whom Ted is drawn. Virginia is a future version of Valerie, time-traveled into Valerie’s present.

JZ: Virginia does seem “over” some of the problems of femininity and young womanhood that plague Valerie, like objectification and finding one’s agency in transactional heterosexual relationships. Can you talk about how the novel deals with female subjectivity?

VW: Menial art-world labor is incredibly gendered. There’s this trope of the “gallerina,” the frosty and fashionable young woman sitting at the front desk or bringing espressos to the private viewing room. At the gallery where I worked, all of the art handlers were men. You could obviously read into this division of labor the very schematic distinction that Laura Mulvey identifies in Hollywood cinema, in which the male protagonist acts to move the story forward and his female love interest is a passive image who halts the narrative for moments of visual pleasure. Mulvey’s point is that this situation produces a ton of anxiety for the male protagonist—is he supposed to keep the narrative moving, or is he supposed to stop and look at a hot lady? But I think it’s an anxious situation for the woman, too! Is she really just a passive object? Doesn’t her objecthood do narrative work? In the gallery context, the gallerina establishes the atmosphere of the space. She’s a mediator—she answers the phone, writes emails for the directors, speaks about the exhibition with visitors, interfaces with clients when they arrive. Valerie grapples with this double bind of being both a subject and an object in the book.

The narrative is fragmentary, and often splits off from Valerie’s experience to fold other women in, like Leila or Xiao. These women are doubles for Valerie, insofar as being categorized as a woman produces certain shared experiences and traits that can be points of solidarity or friendship, but they’re also themselves, since no category is ever totalizing. One thing that all the women have in common—except perhaps Virginia, who uses Ted as a surrogate man to possess other women, and Julie, who is queer and so rejects heteronormative narratives—is that they can’t figure out how to be active protagonists, how to exert agency, while also recognizing themselves as subjected to objectification. Of course, absolute agency is a myth, even for men. And New York is a great place to work through these questions, because it’s a city that embraces wild performances of all kinds of positions and identities, but completely mocks the idea of heroic subjectivity. No one is New York’s protagonist. The city is indifferent to your little life, which is great—you can feel your anonymity and unimportance. If you’re like Ted, you can get wrapped up in a picaresque of masculine performances, but this isn’t real heroism, and it isn’t a narrative.

JZ: Would it sound right to you to describe THIEVES as a feminist novel?

VW: I’m not sure—that depends on your definition of feminism, or what kind of feminism is called for in a particular historical moment, which may have shifted since I wrote the first draft in 2016! It’s definitely a book that grapples with female subjectivity, and specifically the structure of white female subjectivity under neoliberal capitalism. I thought a lot about the feminism of writers like Chris Kraus and Cecilia Pavón, who oppose the idea of a unitary self that can be lived or written with a ceaselessly temporal mode of writing. Kraus and Pavón are both explicit about the conditions under which they write, the ways they’ve been written as women before being able to write as women, the relations and friendships and lineages that make their lives and work possible.

In the final section, Valerie leaves New York, empties her bank account, loses her lover, and begins to explicitly plagiarize her former self rather than producing any new language to grease the wheels of art-world capital. Maybe this feminism is like Lee Lozano’s “dropping out”—not an active protest but an intensification of passivity that shatters the eager complicity typical of white women, or of a lean-in, liberal feminism. At the end of the day, gender is a labor relation, and the novel is an individualistic form, a bourgeois form. A novel can’t abolish capitalism or gender. Maybe it can present an alternative, but that’s not what I tried to do in this book, though the final page could point toward a utopian vision. There’s a line earlier in the book about not being able to exit the symbolic order of real life. The final page is some small attempt to point to the contingency of that symbolic order, the possibility of something else beyond or after it.

JZ: Speaking of “pointing to something beyond”—what are you working on next?

VW: I’m working on my dissertation, “Body Camera,” which is a scholarly refraction of my obsession with the concept of the shifter. The letter “I” is the first-person shifter in the English language: it stands in for something specific and concrete, and in standing in for that entity, it absents it from the text. Basically, I can type “I” and trust that you’ll hallucinate some sort of subjectivity into that letter, but that same “I” could refer back to many different subjectivities. Anyone can say “I.” My dissertation proposes that worn and handheld cameras like the iPhone have created an audiovisual first-person shifter that is now more efficacious in legal and public discourses than the linguistic one. Handheld videos are the new way we say “I,” and watching these videos is a form of bodysnatching. I’m specifically looking at police bodycam videos, which I think whittle state violence down to the scale of first-person individuality. Bodycam videos personalize the state; they contribute to the idea that the problem of policing is a “few bad apples.”

I’m diving back into my second novel, The Irascibles, which I abandoned when Rebecca Wolff and I started working on revisions of Thieves. The Irascibles is a noir erotic thriller set in the booming Manhattan art scene of the early aughts. It follows three women—Elaine, Andrea, and Zhen—who are bound in intimate relations of destruction and dependence by the global art market, even though they never three occupy the same room. I won’t say more about it now than that! I’m also at work on a video, The Private Discourse of Others, with my friend and co-conspirator Max Bowens. We received a massive archive of police bodycam footage from a group of lawyers in the Midwest, and are scanning through the footage to find moments in which cops silence their bodycam or cover the lens, effectively monopolizing the “right to remain silent” for themselves and rendering a device that’s supposed to produce “transparency” into another means by which the blue wall of silence is reinforced.

JZ: You’ve shared a number of photos from your time in the art world / in NYC / in the writing of the book — I’m going to post an array over to the left — do you want to share any info/thoughts/tales about any of them?

VW: Yes! I sent about seventy pictures and you posted almost all the pictures of me that I shared, which is funny, because I so rarely take selfies and dislike having my picture taken. The moment of posing for a picture is a real point of panic: I have to somehow resemble myself, invent a spare body and face to be transformed into an image that will then come to rule over me, to be what I need to continue to resemble. This image that rules over me already exists, of course, in the form of the cliché. I’m reminded of the scene in the novel when a GUESS advertisement begins speaking to Valerie in Miami, telling her to come join her in the photographic realm, in part because Valerie already so thoroughly resembles the photographic that her assumption (in the Catholic sense) into image-form would be the most logical conclusion of her fleshy existence.

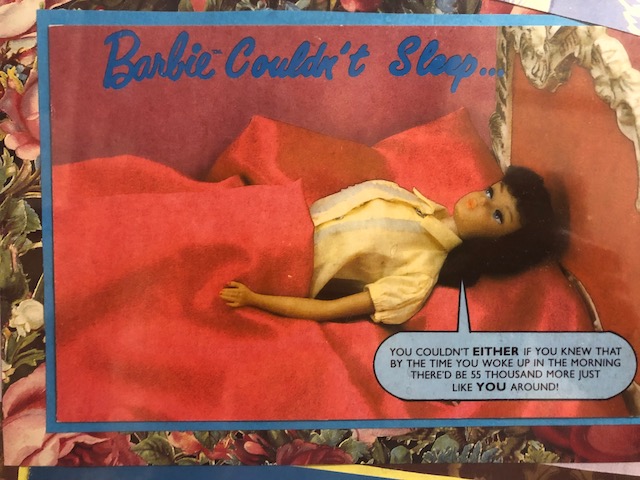

I take selfies, or allow my picture to be taken, when I feel this cliché image very closely coinciding with “me.” It’s both a protective shield—my friend Keisha Knight refers to it as “avant-garde killer Barbie”—and a threat, because a worn image seeps into the flesh and comes to constitute the self. In Deleuze’s Cinema books, he describes the films of Robert Altman and Jacques Rivette as being “a conspiracy of clichés.” Particularly in Nashville and Le Pont du Nord, clichés do the bulk of the narrative work, and the characters both are clichés and operate with a distinct sense of paranoia at having become cliché, like, “Who or what did this to me? And how can I kill this cliché that is myself?!” Valerie grapples with this problem in the novel, and I grapple with it any time my image is taken.

I took other pictures in moments of consumption—whether art-world or supermarket consumption—when I could feel realism collapse into genre. “Genre” is the name given to any writing that supposedly doesn’t properly represent lived experience, but lived experience doesn’t always adhere to the bounds of literary realism! For example, the image of the supermarket advertisement reading, “We love you! We really do!” or the door to the museum gift shop simply labeled, “Art”—those images have no place in literary realism, but they are reality.

I used to pick up my boss’s dry cleaning, and I became obsessed with the hangers that read “We ❤️ our customers.” Supermarket love, the greedy tendril of love in which capital ensnares its customers, can be eerily close to romantic love. Transactional romantic love is about wanting to be wanted, wanting to be selected from all the available options and brought to the checkout line and taken off the market. Some art objects call out to me in this way. They want to be wanted, to be collected, and so I take a picture of them. Those weird little candles in Mike Kelley’s The Wages of Sin—they want me to love them! Other artworks are totally indifferent as to whether or not I love them: Ana Mendieta’s Soul, Silhouette on Fire or Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit. Those pictures weren’t taken by me—I grabbed them from the Internet.

It may sound like I’m setting up a dichotomy in which one kind of art, indifferent art, is better than the other, art that wants to be wanted (and, in wanting to be wanted, renders itself into a consumable image). It might be possible to create an object that fits into one category or the other, but I don’t think it’s possible to live or love entirely in one mode. I’m both indifferent and a desiring cliché, and so is Valerie. Like, I don’t give a fuck if you love me, because I never fully coincide with myself, but also, please love ‘me,’ which means, please love this thing that is always also a cliché.

We ❤️ you, customers.

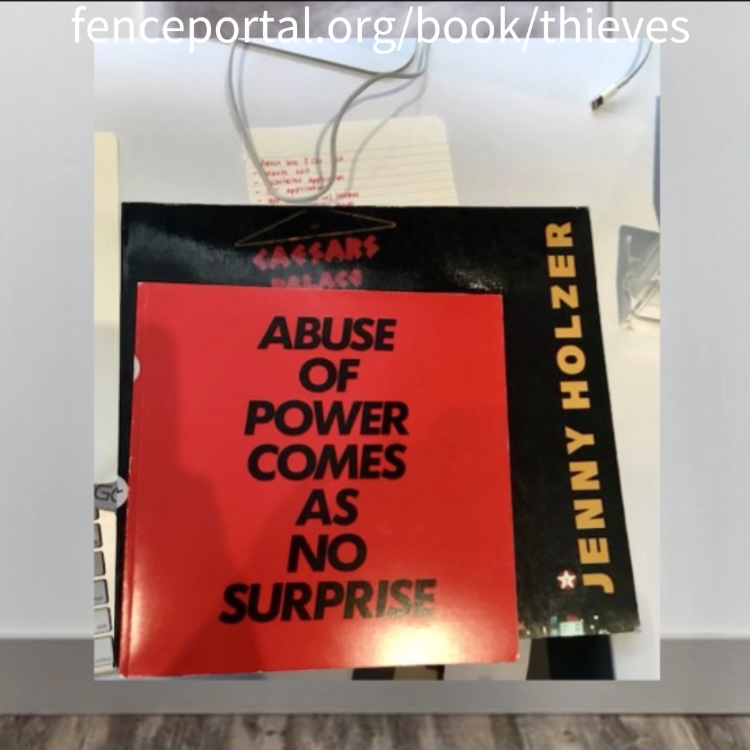

Captions for images above:

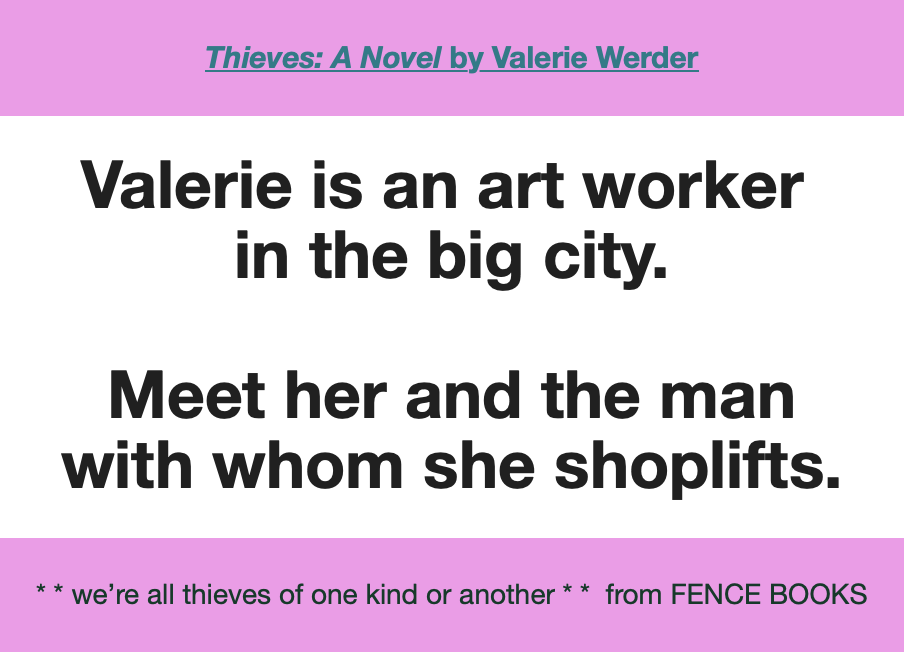

2. Art Workers Coalition, Art Workers Won’t Kiss Ass (1969)

11. Diedrick Brackens, Nuclear Lovers (2020)

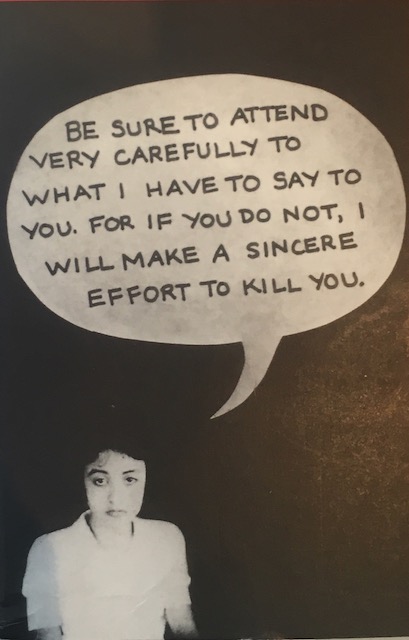

13. Adrian Piper, I/You/Us (1975)

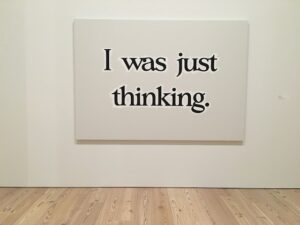

15. Ricci Albenda, I was just thinking (2009)

16. Mike Kelley, The Wages of Sin (1987)

21. Gillian Walsh, Scenario: Script to Perform at the Kitchen (2015)